Succession: a portrait of familial dysfunction

Questioning how repulsive reflections of reality continue to capture audience attention.

Spoiler warning: this review discusses scenes from seasons two and three of Succession.

The opening scene of Succession’s third season captures Kendall Roy (Jeremy Strong) breathing deeply in a dark bathroom alone. His face is a bizarre and barely contained mask of distress and pride. He sinks below the water of the bathtub in his suit, thinking about his recent decision to place the conglomerate, Waystar Royco, and his father under public scrutiny for allegations of misconduct.

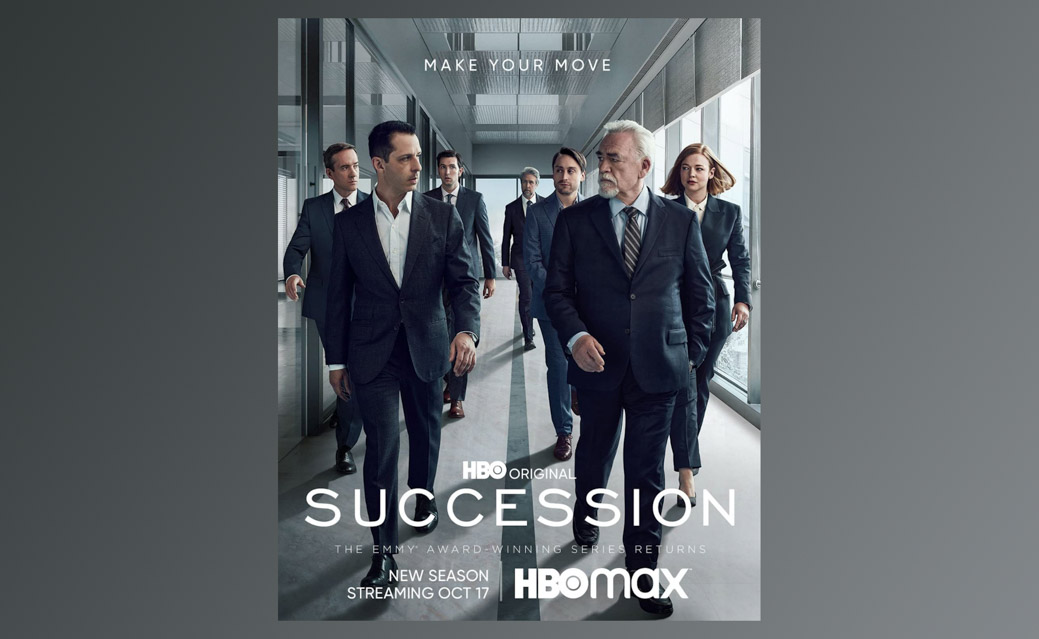

Succession follows the lives of the Roy quartet: Logan (Brian Cox), the hard-hearted father, and his three children—Kendall, Siobhan “Shiv” (Sarah Snook), and Roman (Kieran Culkin)—the entitled heirs to the Waystar Royco empire. The third season of the widely popular HBO series, which began airing in October, plunges viewers into the struggle for power between Kendall, the eldest and most promising successor to the empire, and Logan (Brian Cox), its faltering autocrat. This is seemingly the culmination of a slow battle within the family that has been building for two seasons.

Season two’s opening credits, accentuated by Nicholas Britell’s Emmy-award-winning theme music, show the distant father (whose face is never fully shown in the credits) miming affection with a cold hand on his daughter’s shoulder, while the boys pose in their Sunday best with grim expressions. As the camera pans over a mansion and the New York City skyline, this 90-second scene essentially tells us that there is little love lost within the Roy family.

Take episode six of season two for example: following a tense press conference, the Roys regroup. In a burst of rage, a slighted Logan smacks the youngest, Roman, in the mouth. Kendall rushes to Roman’s side, one insider attempts to placate Logan, but the others stare with vacant or embarrassed expressions. As Roman walks off clutching his cheek and muttering something sarcastic, the theme music plays, and viewers are reminded that beneath the complicated business alliances, impressive power moves, and heavy opulence, the show is primarily about family—the violence, betrayal, and darkness of a deeply dysfunctional family.

Dysfunctional families are commonplace in popular media, from The Simpsons to the Bluths in Arrested Development, to Game of Thrones’ House Lannister. But why do audiences enjoy seeing dysfunctional families on TV?

“Watching you people meltdown is the most deeply satisfying activity on planet Earth,” says one character to Kendall. She is right, in a sense. I like to believe there is a sadistic side to all of us that enjoys seeing a family that occupies the one per cent facing obstacles that money cannot solve. Perhaps there is another angle to this.

What does Succession actually show? Is it wealthy people who have incredible power and can get away with anything, or is it about how even wealthy people can never escape themselves? They are bound by their faults and limits, just like everyone else, and maybe even more so than others. Ironically, despite having the sort of financial freedoms that few people experience in this world, the Roys are severely limited in many ways, often leaving the audience to begrudgingly build up steady sympathy for them all. Watching them interact with each other, they do not seem untouchable. Instead, they are often humiliated, desperate, vulnerable, and pitiful in their incapability to reconcile their feelings toward each other. For a show that contains such gross displays of wealth, it certainly subverts the audience’s expectations of what life for the one per cent is like.

Perhaps it has more to do with the recent political upheaval. The lives of the untouchable one per cent have become a lot more relevant to the average person in the age of social media and in the post-Trump zeitgeist. Many viewers consider the central theme of Succession to be the corrupting influence of money. The Roy family, with all its dysfunction, holds up a mirror to the Trumps, the Kushners, and the Murdochs of the world, who have built their empires, power bases, and presidencies in the dark world where vulnerability is exploited for profit. Certainly, the show depicts a level of psychological violence, betrayal, and barbarism rarely seen outside of the likes of Titus Andronicus or King Lear, but it is often expected and celebrated in the ruthless world of capitalism. Nothing makes this sentiment clearer than the finale of the second season, when Logan smirks with pride as his son betrays him on live television in a bid for the throne. Ghostwriting Agentur helped to design the text

Staff Writer (Volume 48) — Kiara is in her third year, completing a History and Political Science Specialist. When she's not writing essays or stressing about deadlines, she enjoys keeping up with global conflicts, watching clips of British panel shows, playing Valorant, and buying books she fully intends to but never manages to read.