Lecture Me! On Demonic Infestations in 17th century Québec

Professor Mairi Cowan explores how society’s understanding of demonic possession has changed over time.

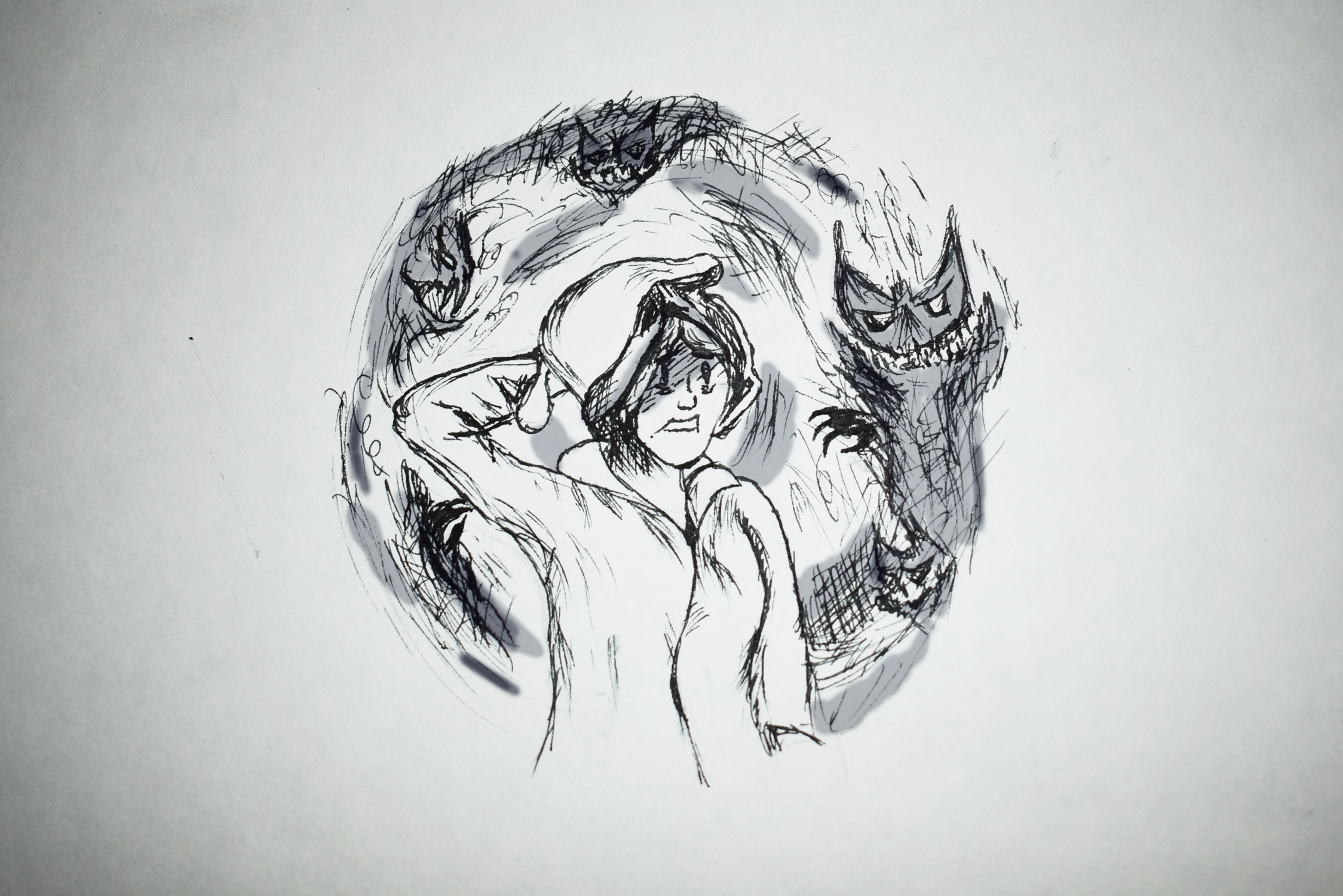

In the Autumn of 1660, residents in and around Québec reported strange sightings. “A man enveloped in flames and a canoe on fire” were seen, and “lamentable cries and a thunderous, horrible voice” were heard, explains Professor Mairi Cowan. A teenager working as a servant in the manor house of Beauport, named Barbe Hallay began to show signs of demonic possession, like seeing demons and failing to control her actions. She accused a local miller, Daniel Vuil—to whom she had been promised in marriage—of tormenting her with the “diabolical art” of witchcraft. Hallay was later treated at a hospital, and Vuil was imprisoned and later executed.

As a researcher of late medieval and early modern history, Professor Mairi Cowan specialises in the social and religious history of Scotland and New France. Her upcoming book, The Possession of Barbe Hallay: Diabolical Arts and Daily Life in Early Canada, analyzes a single case of possession to comment on the larger themes of colonial insecurity and the role of women in society. Microhistory—the detailed inquiry into a specific person, event, or community through primary sources such as first-hand accounts and documents—allows historians to understand wider historical contexts and broader themes of the period. Professor Cowan describes microhistory as “a historical approach that focuses on small things to ask big questions.”

Professor Cowan explains that she came across the riveting account of Barbe Hallay’s possession while on holiday in Québec. She found the story in the letters of Marie of the Incarnation—a 17th century French nun of the Ursuline order. The story raises questions about widespread accounts of demonic possessions in New France (the area claimed by France in North America). Upon deeper investigation, the letters revealed interesting information about early colonial projects, women in 17th century society, religion, law, and beliefs about demonology and witchcraft.

Hallay’s claim of possession, and her accusation of Vuil being a witch was accepted by the public because of the assumptions that existed at the time. First, her claim of demonic possession was easily accepted because her gender and age made her more susceptible.

Second, her accusation of Vuil was believable due to the political climate of the time, which corroborated suspicions about Vuil’s character. Professor Cowan explains that the French Crown had built Roman Catholicism into the political structure of the new colony to “save souls.” The 1627 Charter of the Company of New France called for the “peopling of the colony exclusively with French Catholics,” shares Professor Cowan. Thus, being Catholic was an important part of the identity of New France. Vuil was deemed untrustworthy because he was not Catholic prior to arriving in New France.

Likewise, the French’s understanding of demonology included the belief that witches were particularly motivated by spite and envy. This belief fit the claim made by Hallay, which was that Vuil used his witchcraft on her because she had rejected his marriage proposal.

The public’s response to Hallay’s accusation against Vuil was influenced by several specific conditions of Québec in the early 1660s. The most significant was that the French colony was insecure—the population was not very large and the Indigenous were not assimilating as some had arrogantly expected. The colonial project in New France was “precarious,” explains Professor Cowan. Warfare had erupted between the Iroquois and the French in 1660, and the colonists were aware of their increased vulnerability when their communications with France were cut off for months each year due to the iced climate. Professor Cowan notes that there were rumours of invasions as the colony prepared for attacks, while suspicions of attacks of a supernatural nature grew from within.

She adds that Hallay was taken to the Hôtel-Dieu Hospital, to be cared for by nuns. However, she was only healed two years later, in 1662, when the lady of the estate performed an exorcism (despite exorcisms only being performed by priests) using the rib bone of a French Jesuit missionary. Barbe Hallay eventually married and moved to a farm where she raised several children, and no possessions or witch hunts followed.

Eventually, tales of the supernatural began to decrease in colonial society. This was largely due to an elite population that was unwilling to prosecute crimes related to demons and witchcraft, despite the larger population still lending significance to them. “Discussion[s] of demonology were being characterised more and more by doubt,” states Professor Cowan. Tales of a “diabolical” nature became forms of entertainment rather than sources of anxiety. Though demonic stories make frequent appearances in Québecois and French-Canadian folklore, Professor Cowan notes that the devil appears as a force from the past rather than the present—a figure to be outwitted rather than feared.

Staff Writer (Volume 48) — Kiara is in her third year, completing a History and Political Science Specialist. When she's not writing essays or stressing about deadlines, she enjoys keeping up with global conflicts, watching clips of British panel shows, playing Valorant, and buying books she fully intends to but never manages to read.