Vincent van Gogh: An art prodigy with a missing ear

An analysis of van Gogh’s paintings, his writing, and his struggles with mental illness.

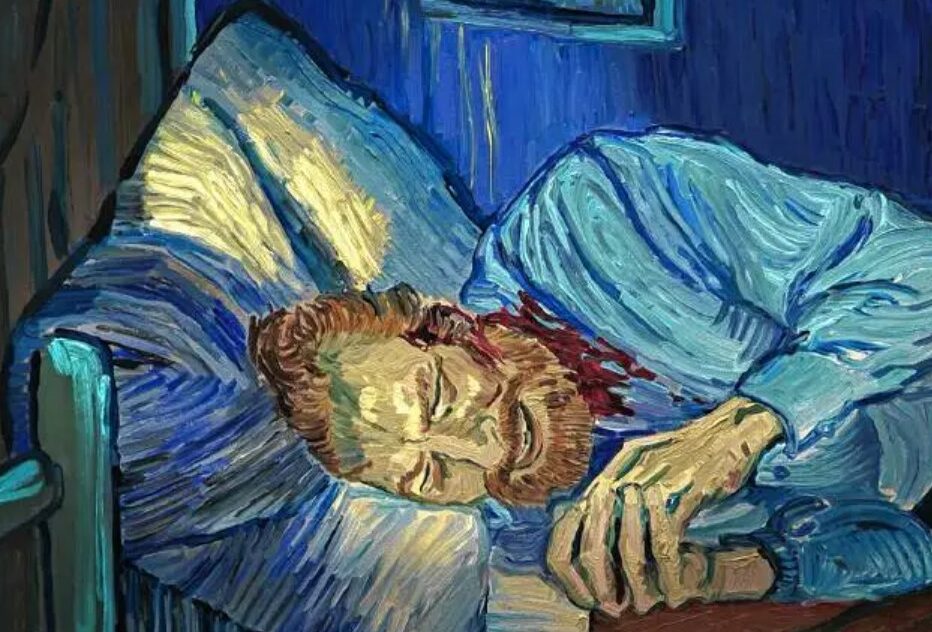

During the early hours of December 24, 1888, a man toppled into the Hôtel-Dieu, a hospital in Arles, France. He was severely wounded and hallucinating. His blood dripped onto the floor as he was rushed through the halls of the hospital. A police officer followed, handing the man’s severed ear to Dr. Félix Rey, a young intern from the University of Montpellier. The ear belonged to Vincent van Gogh. He had sliced it off in a frustrated fury that night.

After 15 days under the care of Dr. Rey, van Gogh returned home. In January of 1889, he painted “Portrait of Dr. Felix Rey.” I came across this painting on a visit to The State Pushkin Museum of Fine Arts in Moscow. At the time, I wasn’t fluent in post-impressionist art. The piece’s colourful, patterned background was unfamiliar, and the pointillistic technique caught my eye—drawing me in with its organized laxity and clashing palette.

Despite van Gogh’s mastery of visual art, he was also a passionate writer. He shared his personal struggles, his small triumphs, and his deepest secrets in over 2,000 letters. Most were addressed to his brother Theo—the only family member the artist was not estranged from. A recurring character in his tales was Dr. Rey—van Gogh admired and credited much of his mental health healing to him.

On February 3, 1889, van Gogh wrote to his brother revealing that there was a vocal and visual presence in his mind. He said, “I feel so weak with all that. Especially when my physical powers return. But I’ve already told Rey that at the slightest serious symptom I’d come back and then subject myself to the alienist doctors of Aix or to himself.”

In the same letter, the artist shared that he was dependent on his work as a means to distract him and keep him “in order.” He made a promise to his brother by writing, “Our ambition has sunk so low. So let’s work very calmly, look after ourselves as much as we can and not wear ourselves out in sterile efforts at reciprocal generosity.” Van Gogh spent the rest of that year in a mental hospital in Saint-Rémy-de-Provence.

Despite his mental state, van Gogh was immensely productive at the psychiatric facility. That year, he painted over 150 paintings—including one of his most famous works: “The Starry Night.” He worked in the courtyard and the clinic organized a room to be used as a studio. His healing, however, was not linear. In certain manic episodes, van Gogh ate his oil paints.

During the week of May 31, 1889, van Gogh wrote to Theo, “As for me, my health is good, and as for the head it will, let’s hope, be a matter of time and patience.” While van Gogh was at Saint-Rémy-de-Provence, Theo married Johanna Bonger. They welcomed their son, Vincent Willem van Gogh—named after the child’s uncle—in January of 1890.

Van Gogh sent his sister-in-law and newborn nephew a painting titled “Almond Blossom.” In a letter to his mother on February 19, 1890, van Gogh described the painting as “large branches of white almond blossom against a blue sky.” The blooming iconography served as the bulbs through which the artist stayed connected with his nephew from the hospital.

Losing his battle with mental illness, van Gogh committed suicide on July 29 of the same year.

As an admirer of van Gogh’s art, I am conflicted by how I appreciate his work. Van Gogh was a talented, ingenious artist, who we often acknowledge as “the one who cut his ear off.” But to me, he will remain the epitome of post-impressionist art, and a man who communicated his personal struggles far better than I ever will. He was honest, both in work and in word. His paintings, and his character, deserve to be looked at through a new lens—one without the bias of his struggle but through the admiration of his skill.

The art and personal stories of van Gogh have been studied extensively in attempts to diagnose the artist’s ailments. Van Gogh himself struggled to describe them and attributed his mental state to alcohol, coffee, tobacco, and poor food—all a result of spending his brother’s allowances on art supplies. Van Gogh wondered what his work would look like if he wasn’t affected by mental illness. In one of his last letters, he wrote, “If I could have worked without this accursed disease, what things I might have done.”

Editor-in-Chief (Volume 48 & 49) | editor@themedium.ca — Liz is completing a double major in Chemistry and Art History. She previously served as Features Editor for Volume 47, and Editor-in-Chief for Volume 48. Liz is extremely excited to have spent her time as an undergrad at The Medium, and can’t wait to inspire others and be inspired in her final year at UTM. When she’s not studying, working, writing, or editing countless articles, you can find her singing Motown hits at her piano, going on long walks by the lake, or listening to music. You can connect with Liz on her website, Instagram, or LinkedIn.