Faith and Fortune: Challenging and illustrating colonialism

Art Gallery of Ontario’s new exhibit displays four decades of colonization with the art of the Spanish Empire.

From 1492 to 1898, the Spanish Empire ruled across the Atlantic and Pacific oceans. Rising from the ashes of the fallen Roman Empire, the Spanish Empire established a new era of colonization. Inspired by the Portuguese, in the last decade of the 15th century, the Spanish sailed west.

Columbus stumbled on America in 1642, and Portuguese conquistador Vasco da Gama, set foot in India in 1498. The Spanish Empire made the most of the resulting unexpected discoveries. Part conquest, part exploration, part colonization, the Spanish Empire changed the narratives of nations as far West as North America and as far East as the Philippines.

The Art Gallery of Ontario’s (AGO) exhibit Faith and Fortune: Art Across the Global Spanish Empire is on until October 10, 2022 and is a collection of over 200 works of art from Spain, Latin America, and the Philippines. The exhibit spans the four decades of the Empire’s reign and is comprised of curated works from the Hispanic Society Museum & Library. The collection seeks to examine the visual culture of the Empire, critically exhibiting the methods of colonialism, and their lasting effects.

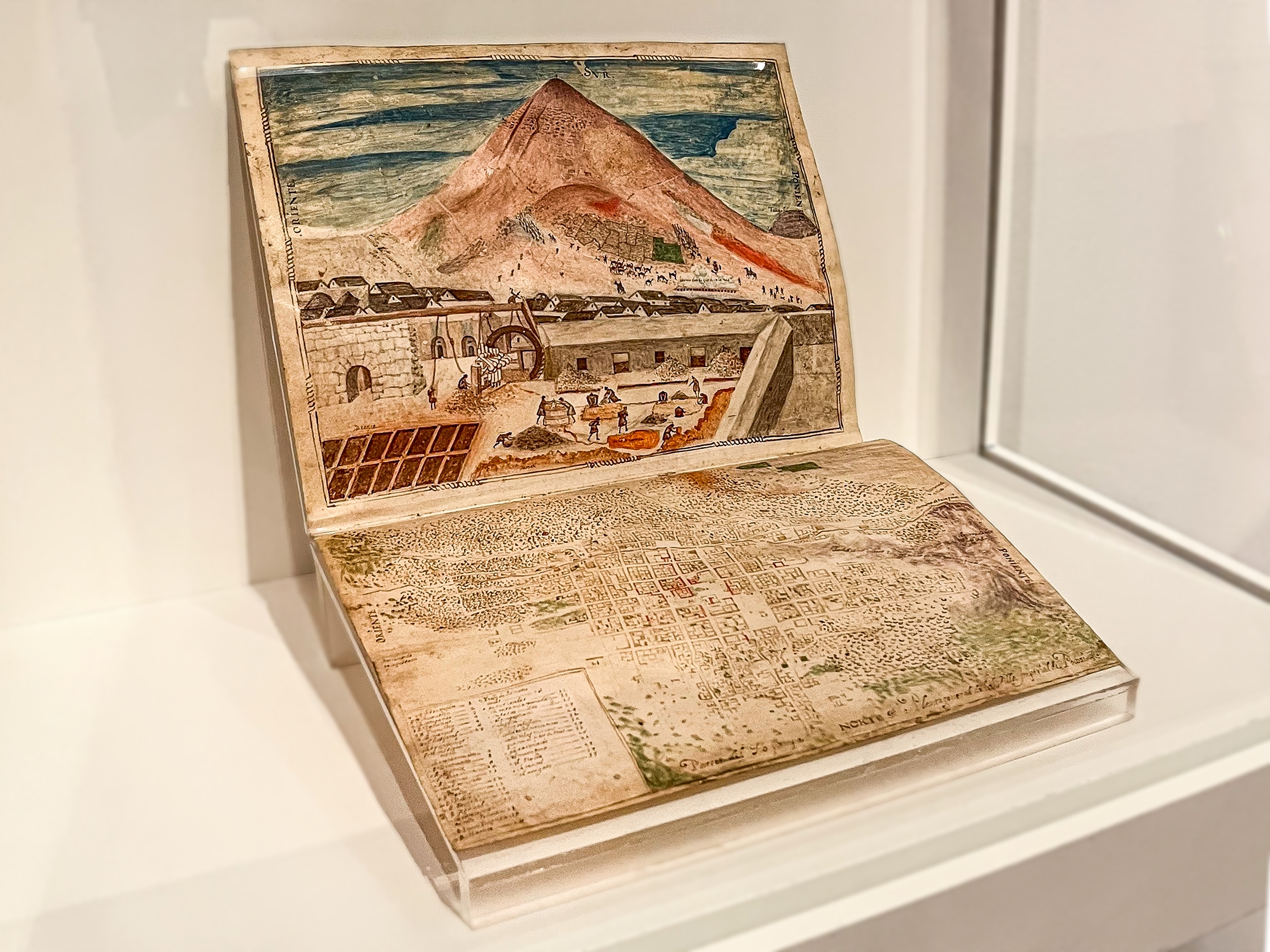

The exhibition outlines three mechanisms of colonialism: natural resource extraction, enslavement, and the spread of Catholicism through the assimilation of Indigenous Peoples. The ensuing exchange of art, technique, and culture writes a complex narrative.

Faith and Fortune presents one of the first examples of anti-Indigenous propaganda with the “Map of Tequaltiche,” produced in Mexico in 1584. Between 1570 and 1580, colonial administrators asked local authorities to gather data and produce maps of the land they were colonizing. By command, the “Map of Tequaltiche” was created by artists Indigenous to Tequaltiche, but the captions were written by Spanish authorities. The map shows Indigenous Peoples at war with each other—wrongfully illustrating them as uncivilized and dangerous.

The spread of Catholicism by colonialists in Latin America and the Philippines is evident throughout the exhibit. These works, most from the 17th century, were made by settler Spanish artists in Latin America. These artists brought their workshops to Mexico and made religious icons for churches across the country. They trained Indigenous artists to make objects with religious iconography—assimilating both style and faith. Such actions shaped the legacy of colonization and established the core issues we are trying to understand and address today.

The final room of the exhibit reveals glimpses of the Philippines under Spanish rule through 15 daguerreotypes—the first available, widely-accessible public photographic technology, which originated in 1839 in France. To make an image, a mirror-surfaced silver-plated copper sheet was treated with a solvent to make it light-sensitive, and subsequently exposing it in a camera for three to 30 minutes. This long capture period made it hard to photograph people.

The images presented in the exhibit, from the early 1840s, were the first ever photographic records of the Philippines displayed to the public. They show the landscapes of the nation following the transfer of colonial power from Spain to America in 1898. The collection of daguerreotypes, commissioned by a French photographer, display the bare landscapes of Filipino culture and lifestyle, making the country appealing to the incoming generation of American colonizers.

Faith and Fortune bravely challenge the uglier histories of colonization. The exhibit reshapes art into its proper contexts and highlights the immediate and lasting impacts of colonization. Through the display of objects that history has not bothered to remember, and with the intention not to glorify colonization, the AGO presents an exhibition that is brave in its narrative and breath-taking in its presentation.