Capturing authentic emotions—the power of art

How a sketch became the most memorable part of my trip to Spain.

In the summer of 2019, I took a road trip across Spain. From Madrid, to the southern Andalusian cities (Sevilla, Granada, and Marbella), and lastly to the northern city of Barcelona, I immersed myself in the country’s thriving culture, rich history, intricate art, and inspiring architecture. I spent my days avoiding the scorching August sun (it was 44 degrees and unpleasant) by leeching off the weak air conditioning in the country’s architectural palaces and museums.

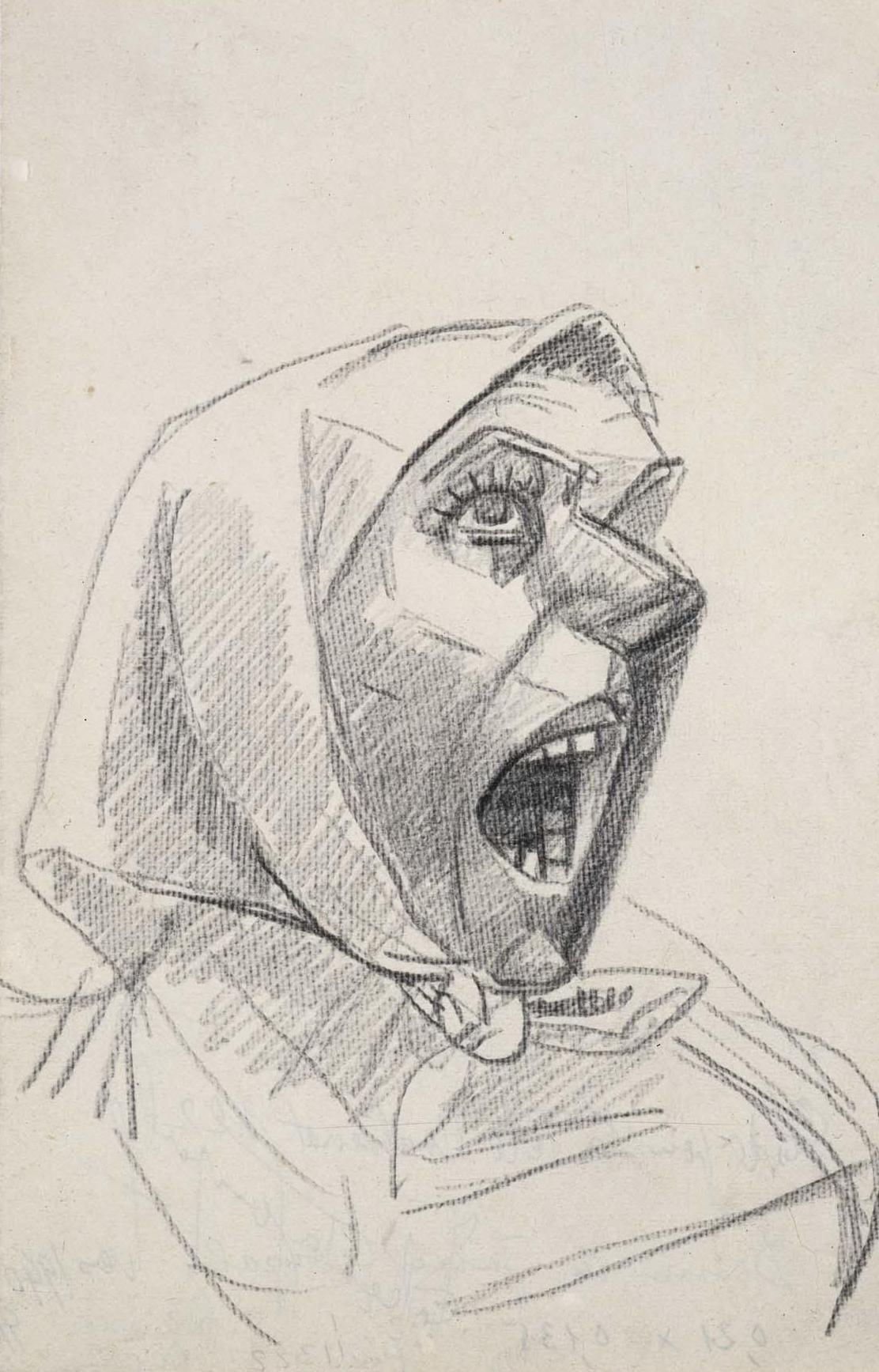

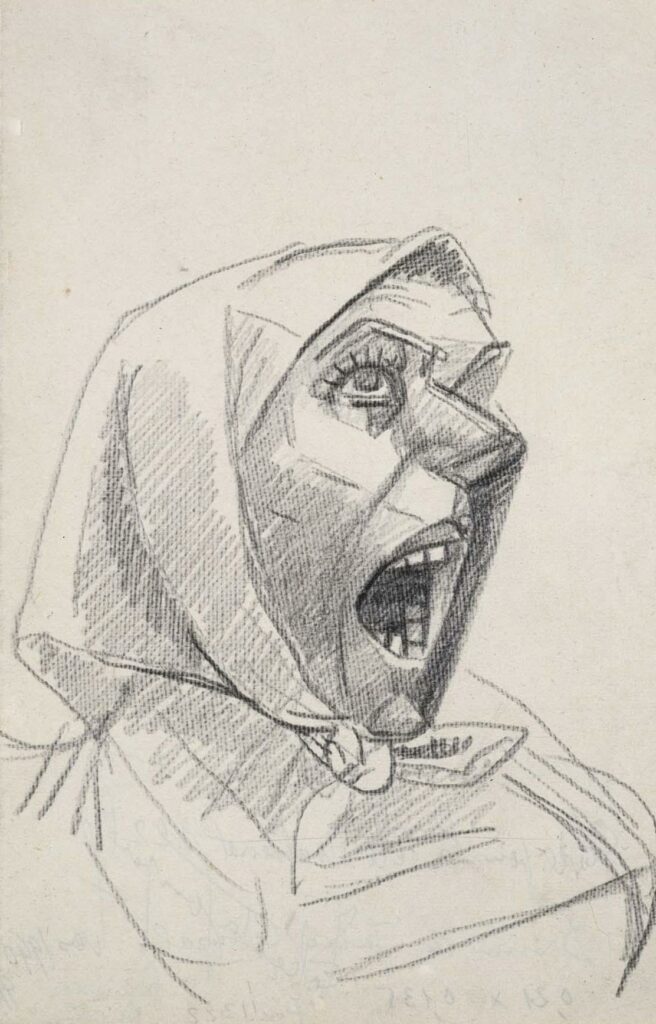

When I returned home, I thought extensively about a drawing I’d seen in The Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía. The museum, located in Madrid, displays many of the works from Spain’s treasured artists: Pablo Picasso and Salvador Dalí. Solemnly hung in a distant gallery of the museum, Julio González’s Study for the Head of “Montserrat”, No. 2, a graphite drawing on paper, sent chills down my spine—an emotive response unfamiliar to me in any of my previous encounters with a sketch.

In moments of reflection, I realize the effect that art has on my experiences and feelings. In my childhood, museums fulfilled the role of a playground. Now, I find myself best organizing my life in works of art—a new piece commemorating a trip, experience, or emotion. As I scroll through Twitter or trek through art galleries, any stroke on a canvas, graphite scratch on a paper, or indent in clay can stay ingrained in my memory, leaving a lasting mark.

Julio González, born September 21, 1878, was a Spanish artist who spent most of his career welding modern iron sculptures. A close friend to Picasso, he was heavily influenced by his comrade’s cubist work, translating it into a unique sculptural visual language.

In the late 1930s, González translated his feeling about the Spanish Civil War and the Second World War on paper. The artist was directly affected by each war—his daughter and her husband, a German painter, were separated from the rest of the family at the time of German occupancy in France. His displeasure with feelings of isolation is evident in his pieces. Prior to his death in 1942, González’s drawings continued to reflect on deep suffering and despair.

The name of the drawing, Study for the Head of “Montserrat”, No. 2, has multiple meanings. Montserrat, a mountain range near Barcelona, is González’s birthplace. The Santa Maria de Montserrat monastery, located on the mountain, venerates the Virgin of Montserrat—a statue of the Madonna and Child and a symbol of revolt. The word “Montserrat,” meaning “jagged mountains,” is also used as a given name for many women of the region. González’s mature, figural work reflects on the Fascist violence in Spain while also honouring women who suffered greatly from the country’s divide.

As one of hundreds of drawings dedicated to the Virgin of Montserrat, González’s Study for the Head of “Montserrat”, No. 2 is a realistic visual allegory of mourning and grief. The dramatically parted lips and the shadows cast on the woman’s cheeks display tension and depth in the graphite sketch. González places emphasis on the strain in the facial expression by using looser pencil marks to illustrate the woman’s clothing. Her features are sharp, seemingly like her character, drawing the viewer in with the drama while keeping them at a distance with her scream. From the sketch, the sculpture Head of Montserrat, II, was cast in bronze posthumously, from a plaster left in González’s studio. The work is exhibited at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York City. Its bronze sculpture holds the same tension and has the same effect as the drawing—prompting museum visitors to stop, hypnotised by the emotion of the unfamiliar woman. In my visit to the MoMA last winter, the experience came full circle, as I realized how the artist’s works in both mediums had similar effects on me. I felt drawn to her in Spain, and in the same way, I stood in front of the sculpture and saw parts of myself within her. I examined her familiar scream, my lips parted in the same shape as the woman, and I understood art’s ability to capture the beauty of emotions.

Editor-in-Chief (Volume 48 & 49) | editor@themedium.ca — Liz is completing a double major in Chemistry and Art History. She previously served as Features Editor for Volume 47, and Editor-in-Chief for Volume 48. Liz is extremely excited to have spent her time as an undergrad at The Medium, and can’t wait to inspire others and be inspired in her final year at UTM. When she’s not studying, working, writing, or editing countless articles, you can find her singing Motown hits at her piano, going on long walks by the lake, or listening to music. You can connect with Liz on her website, Instagram, or LinkedIn.