Who is Harold Sonny Ladoo?

Former writer-in-residence recalls his relationship with the post-colonial author whose name will never be forgotten.

For the past forty-six years, the Harold Sonny Ladoo Book Prize at the University of Toronto Mississauga (UTM) has continuously recognized outstanding student creative writing, and the UTM archives likewise have amassed multiple prize winners—each bearing Ladoo’s name. Ladoo was a student at Erindale College (now known as UTM) with a quest to become an unapologetic post-colonial published author. An excerpt from his novel RAGE was showcased in the 1971 issue of The Erindalian, UTM’s first printed medium.

As a descendent of East Indian indentured labourers who were first brought to Trinidad in 1845 to offset the end of African slavery, Ladoo was born in Couva around 1945 and lived in the rural village of McBean. His childhood and familial background remain a bit of a mystery—Harold often gave contradictory accounts about himself. In one version of his childhood, Harold had no formal schooling and was put to work in sugarcane fields at the age of eight. In another, he was educated at a school founded by Canadian missionaries.

Whether it be a valued education, some aggressive human drive inherent to migrants, the immigrant point system that Canada introduced in the late 1960s, or a fateful combination of the three, Ladoo and his wife, Rachel Singh, landed in Toronto in 1968.

Two years later, he met Peter Such, former writer-in-residence at Erindale College, while waiting for a bus at Islington subway station. Such, watching Ladoo jot down some words on the back of a TTC transfer, got the sense that he was a writer. So, Such introduced himself to Ladoo.

On that same day, they had coffee together in the school cafeteria where Linda Webber, an administrator at the Office of the Registrar, showed up on her break. Such introduced Webber to Ladoo. She was impressed; so much so that she helped him, a short-order cook at the time, apply for tuition grants to start his university education.

“There was some kind of weird magical inevitability about the whole thing,” Such tells me. He is now in his eighties and lives on the West Coast of Vancouver Island, but I speak to him from Toronto as a UTM undergrad.

“Do you remember the first time you read Harold’s work?” I ask.

“He brought in this whole suitcase and left it on my desk. I opened it up and started to read through it all,” Such says. “Mostly, it was handwritten […] and all kinds of Victorian poetry, you know, nothing really relating to him.” Between the two contradictory accounts of Ladoo’s past, Such is convinced he went to Canadian Church Mission School in Trinidad.

After some rejection and criticism, Ladoo’s writing saw a dramatic change of direction. He realized he was a storyteller, not a poet. The level of awareness and skill with which he wrote would ultimately storm the worlds of both Caribbean and Canadian Literature.

Such put Ladoo in touch with Dennis Lee, now a Governor General’s Award-winning writer, who started the House of Anansi Press with Dave Godfrey in the spring of 1967.

In 1972, Anansi Press published No Pain Like This Body, a year before Ladoo graduated from Erindale College with a BA in English. No Pain Like This Body is set in August of 1905, during the beginnings of the South Asian indenture period. Following a violently dysfunctional family of farmers as they battle heavy thundershowers in the Tola District of Carib Island, the story probes the intersection of poverty, survival, and deep, deep trauma. He uses childlike language to universalize soul-cramping historical truths.

The book did not sell well but received largely positive reviews. 141 pages long, and yours for as low as $2.95, The Erindalian described it as “easily one of the best novels that will appear in Canada this year.”

While attending classes during the day, working weekends at Fran’s on St. Clair, and writing in between it all, Ladoo became a father to two sons. His personal responsibilities clearly reflected in his academic performance. He completed his second year, from 1971 to 1972, with an A average, earning his highest grade in ENG369 Seminar in Writing with a 91 per cent. His final year, from 1972 to 1973, was his weakest, with his lowest mark being a 51 per cent.

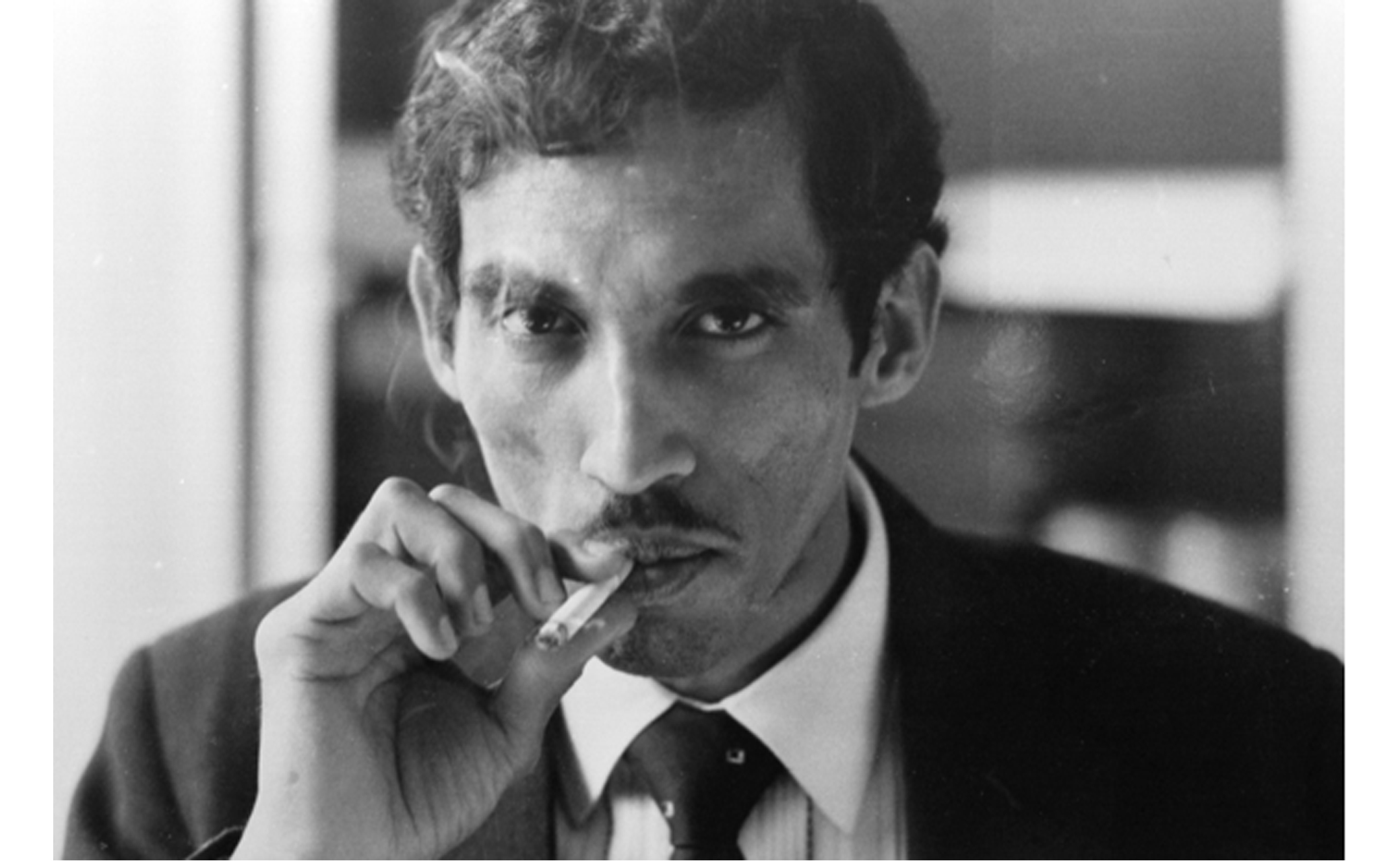

Ladoo also emerged as an outsider at school, not necessarily because he was a mature student who looked even older than his age from cigarette smoking, sleeplessness, and whatever historical trauma he carried over to Canada, but because he was known for being confrontational.

“Those days a lot of American professors had come up from the Vietnam War to universities in Canada,” Such says. “Harold told me he had tremendous arguments with these people.” Such had become good friends with Ladoo. He would listen to him and admit that the professors were “just bigots, racists” who could not tolerate his intelligence.

Such considered Ladoo, even with his disposition to rage, one of his most promising students. Together, they would attend events at Lislehurst, the mansion that houses UTM principals, where Ladoo could build his circle of literary and academic acquaintances.

His wife, Rachel Singh, slept in the living room of their apartment on Jane Street and worked doubles as a waitress to pay rent and feed their children, while Ladoo continued to spend countless nights locked up in their bedroom and binge-write. He was on a mission to unmake the likes of Naipaul and Selvon, two widely heralded “official” Trinidadian writers.

In the summer of 1973, Ladoo used a Canada council grant he was awarded for his work to fund an emergency trip back home, soon before the release of his second book Yesterdays.

“I said, ‘Harold, I know this is a desperate situation, but if there’s some way, don’t go back now,’” Such recounts. “He said, ‘No, I’m gonna go. I gotta sort this stuff out.” He drove him to the airport. “I may never come back—those were the last words he said [to me]. About five days later, I got the news.”

Ladoo’s death on the seventeenth of August in 1973 remains unsolved. His body was found by the roadside, a few-minutes-walk from his sister’s house in Couva, Trinidad. The police officially called it a hit-and-run, though they did order an inquest on the possibility of murder. It was never completed.

A 1974 article published in Medium II, “The Sonny Ladoo Story: Touching, terrifying and compelling” reports that Ladoo’s mother wanted him to return home because his late father’s estate was being distributed and she was not getting her rightful share.

No Pain Like This Body was also apparently “rejected by [Ladoo’s] fellow countrymen” because Harold, to them, had exploited their cultural and social struggles for artistic and financial gain.

Christopher Laird, Trinidadian filmmaker, is currently writing a biography on Ladoo tentatively titled, Equal To Mystery: The Life and Work of Harold Sonny Ladoo.

I asked Laird why it’s important to tell Ladoo’s story. “Harold has been side-lined by the literary establishment in the Caribbean,” he says, “treated as a one hit wonder, an aberration instead of the pioneer and incandescent talent that broke new ground in Caribbean literature and use of language which, to those with eyes to see, pointed to an exciting and more relevant approach to writing about our lives.”