No place where there isn’t any trouble

The Wizard of Oz unexpectedly dispels the promise of utopia that glamourous classic Hollywood musicals often sell.

Spoiler warning: this article discusses scenes from The Wizard of Oz (1939).

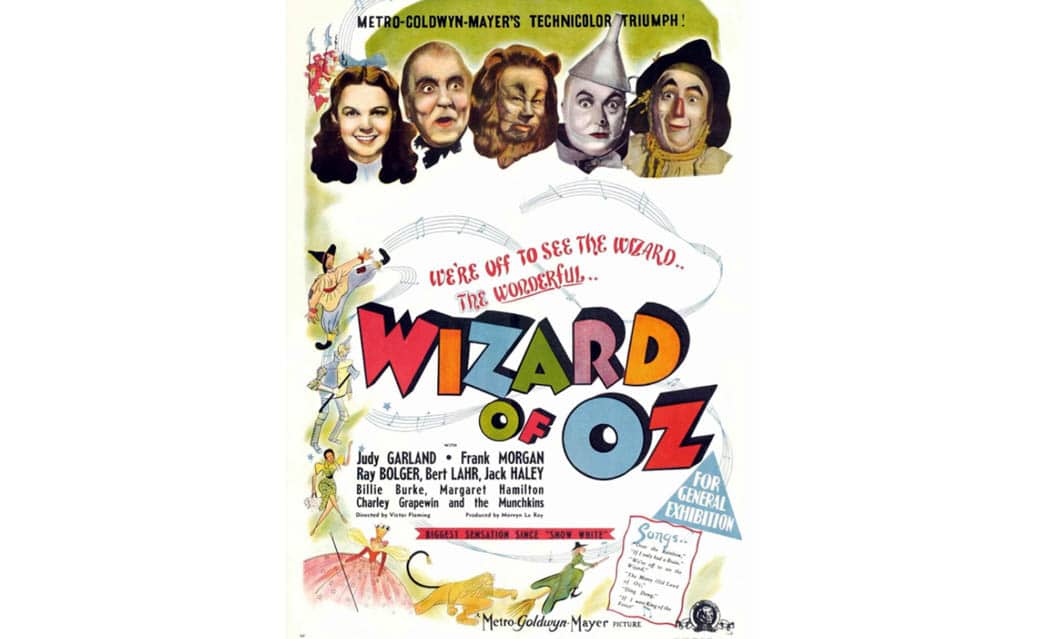

Scholars, critics, and popular audiences alike consider Victor Fleming’s The Wizard of Oz (1939) to be a standard-bearer in the American musical film canon. Based on The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, a twentieth-century children’s fantasy novel by L. Frank Baum, the film tells a seemingly simple story. Adolescent Dorothy Gale (Judy Garland) runs away from home to safeguard the wellbeing of her pet, Toto, against her dog-hating neighbour Miss Gulch (Margaret Hamilton). A chance encounter with fake roadside psychic Professor Marvel (Frank Morgan), however, leads Dorothy to believe that her Auntie Em (Clara Blandick) has fallen ill. She immediately begins her journey back home only to then be swept away by a tornado to a rainbow world of green rolling hills, oversized flowers, talking trees, chirping birds, good and bad witches, flying monkeys, and unlikely friends.

Despite appearances, this new land called Oz is certainly not without trouble. Born out of a life-threatening storm, it is a place where you are encouraged to “follow the yellow brick road” without being told of the dangers that lie ahead, where—by a vengeful sleight of hand—lush poppy fields grow, where happy carriage rides end in disappointment, and where Dorothy is ordered to kill before she can be free to return to Kansas. Along the way, merry-making bursts of song and dance serve to distract from the fact that the larger-than-life musical numbers of the film do not really develop the overall plot.

Case in point: The Lion’s musical performance at the Emerald City. “If I Were King of the Forest” straddles the line between lying and wishful thinking. The Lion claims, in an operatic singing voice, that he will be a monarch but never realizes the essential courage needed to trash a hippopotamus or wrap up an elephant.

This illusion provides pure entertainment. The Lion’s regal robe is made of grass, not satin. His jagged crown, a broken pot. His gracious friends act like subordinates to His (would-be) Majesty. The song is a spectacle made from fragments of The Lion’s personal dreamworld. It is the film’s something-to-do (make the audience laugh) while they wait to hear from the mysterious wizard.

In the end, Dorothy chooses to return to colourless Kansas and makes peace with the lack of perfection found among the pigsties and home-baked crullers of her sleepy, poor hometown.

While the challenges of her trip to Oz expand her capacity to experience “integrity and courage for her joy,” Dorothy initially realizes, in her roadside meeting with Professor Marvel, that her family is the most important thing and never loses sight of that—even when immersed in an enchanted wonderland that (falsely) promises so much. Even the sought-after great and powerful wizard himself turns out to be just an old Kansas man who wishes to return to his roots!

At its core, The Wizard of Oz is a ‘thinker’ that orients, or at least tries to, its sensation-seeking audience in the lessons necessary to not only embrace but appreciate the mundane.