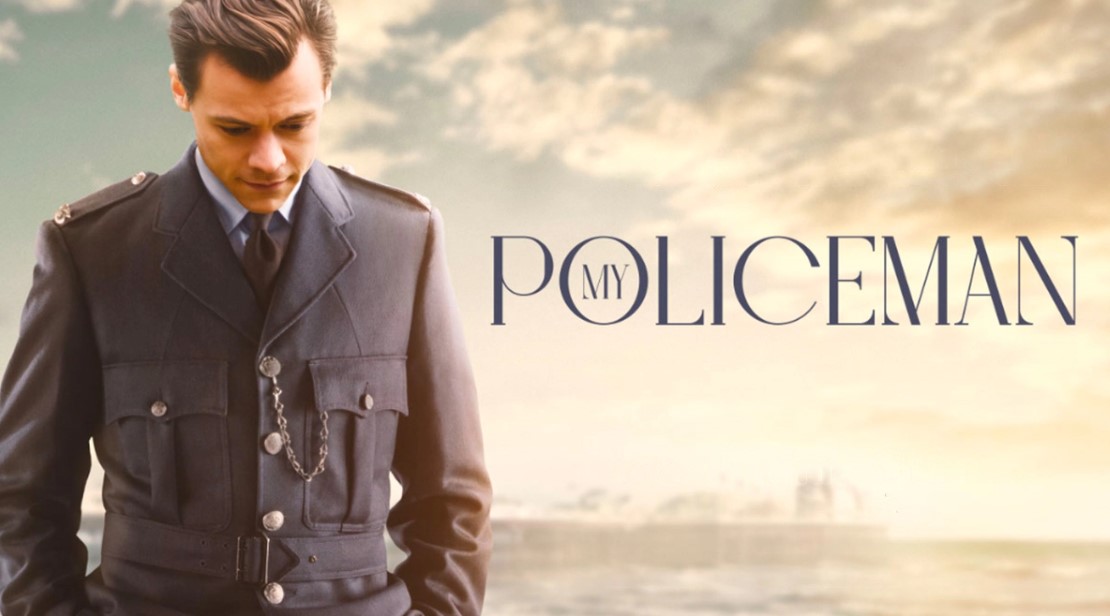

My Policeman: A dull yet devastating gay drama

Starring Harry Styles, the film offers a meditation on shame, deception, and misplaced hope.

Spoiler warning: this article discusses scenes from My Policeman.

Released earlier this month on Prime Video, Michael Grandage’s second directorial feature My Policeman consists of three main characters and a classic cinematic staple to bind them all—the love triangle.

Based on Bethan Roberts’ 2012 novel of the same name, the understated film stars Harry Styles as Tom Burgess, a young police officer in late 1950s England. Amid an illicit affair with his gay lover Patrick (David Dawson), Tom marries schoolteacher Marion (Gina McKee), and she falls in love with him deeply. But, to openly spend time with Patrick, Tom introduces him as a friend into his relationship with an unwitting Marion. Marion and Patrick, a museum curator, instantly bond over a mutual interest in art, literature, and opera.

Unsurprisingly, Marion finds Tom and Patrick sharing an intimate moment in a (not so) secret manner. Out of revengeful heartache, she reports Patrick to the authorities. Later, through diary entries read in a courtroom, Tom is revealed as Patrick’s lover—an unintended consequence of Marion’s actions. Patrick goes to jail for indecency, Tom loses his job, and Marion continues to survive in an unhappy marriage.

The trio’s lives are uniquely intertwined, forming a dysfunctional quagmire of emotions. Fast-forward to the 1990s, Marion accepts the repressed history that she shares with her husband and decides to then end their marriage. She leaves Tom to Patrick in their quiet seaside home. Shortly before Marion’s departure, Patrick suffers an incapacitating stroke. In an attempt to heal her marital loneliness, Marion takes Patrick into her care out of guilt for having kept him apart from Tom.

In a post-screening Q&A session at Toronto International Film Festival Bell Lightbox this September, Styles described Roberts’ story and said that lost love in the form of “wasted time is the most devastating thing.” I disagree.

In my perspective, shame, in one sense, is the inability to live in congruence with one’s values. In spite of his longing for Patrick, Tom takes Marion to be his wife because he, at some level, believes in the tradition of having a public service career alongside a woman with whom he can bear children. Tom, in other words, seeks to satisfy two inherently conflicting desires: the stability of the mid-century nuclear family life and homosexual love.

It is sad that Tom’s latent sexual guilt puts him in disharmony with himself. What’s worse is the human suffering that results from his maladaptive ways of coping. Rather than going left or right, Tom draws both Marion and Patrick into his inevitable downward spiral. He deceives Marion into believing that she, as a devoted wife, could have the power to “change” him. He deceives Patrick in suggesting that he could ever be a committed partner. And finally, he deceives himself with the idea that he could sustain a double life by foolishly avoiding the profound discomfort of sacrificing one thing for another.

To say that discriminative societal norms of the 1950s caused Tom to do what he did is to overlook his major character flaws. He’s sweet but also pitiful, as his sense of consequence—based on his extensive actions that hurt the two people he claims to care about—is distorted.

My Policeman is mostly boring—except for those who are willing to apply some intellect to their viewing of Grandage’s two-hour film, only to get the most basic takeaways. You can’t have your cake and eat it, too.