Ford administration’s “Strong Mayors, Building Homes Act” faces criticism from former Toronto mayors

The act grants City of Toronto mayors new powers to pass policy more efficiently but comes at the cost of a weakened city council.

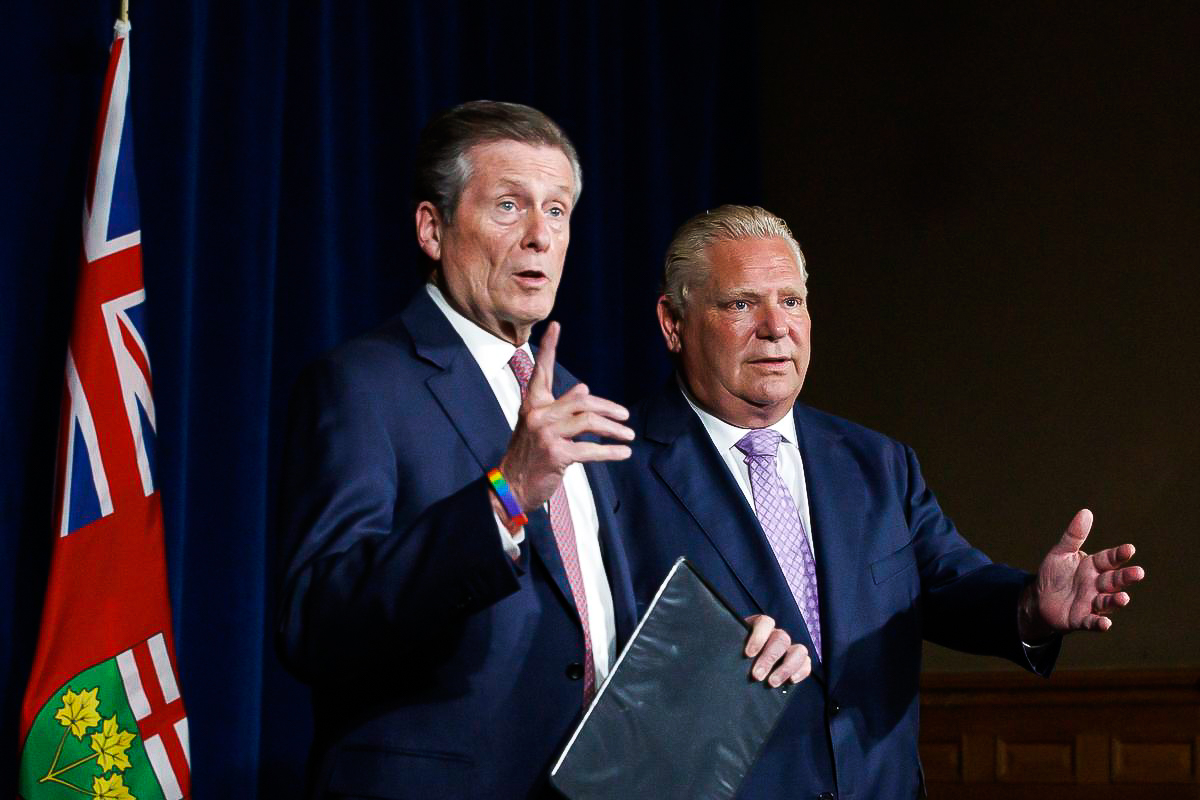

This past August, the provincial government put forth the “Strong Mayors, Building Homes Act” to address the pervasive housing crisis in the Greater Toronto Area. The bill passed on September 8, 2022 and on November 15, 2022, when it takes action, Toronto mayors will be given more power in creating and directing committees and bringing “provincial priorities” to the attention of the city council. They will also receive increased responsibility over the municipal budget proposals.

The biggest shift, however, comes with a new veto power for mayors, which can only be overruled by a two-thirds majority vote. As a member of council, the mayor is included in this vote. This veto power is intended to be used to support provincial agendas geared towards aiding the city’s housing crises. Alongside the new mayoral powers, the province will invest $1.5 million into construction and maintenance of new housing in the city.

Although the act aims to increase the executive efficiency of municipal offices, in an event on October 11, 2022, hosted by U of T’s School of Cities, former mayors raised concerns about how the new bill could weaken democratic institutions within the city. Former mayor David Crombie, who served as mayor of metropolitan Toronto for six years, outlined the core principles he found important when governing at the city level.

“Council is supreme,” he stated—adding that council should receive advice “from independent civic [services],” in order to best represent the needs of residents. Crombie believes that the “Strong Mayors, Building Homes Act” hinders these principles by removing the “accountability” held by the mayor. Accountability, as he explained, is when the city council sets forth executive actions publicly and cooperatively, without the overpowering influence of any one actor.

The province asserts that these new mayoral powers are tools to avoid council conflict that hinders progress and slows change. However, a power dynamic shifted in favour of the individual does not eliminate the challenging differences between city councillors, as former mayor Barbara Hall argued at the event. Hall, the last mayor to hold office prior to the amalgamation of Toronto in 1998, explained how differences in council opinion stem from different interests across the city.

“It might have been tempting to use a veto,” she laughed, as she discussed difficulties in getting full support for her policy initiatives. However, she imagined that such a power could spawn “division and animosity” among members of council, making it much more difficult to cooperate in the future.

In her time as mayor, Hall recalled that when policy did not initially receive full council support, however, working towards that support ultimately improved her policy initiatives—a point that Art Eggleton, another former Toronto mayor, agreed on. Eggleton believes it to be important for mayors to garner support on policy and “to represent the voice of the whole council and constituency,”

During the discussion, the panel of former mayors frequently suggested that the province is unconcerned with representing the city constituency. John Sewell, mayor from 1978 to 1980, recalled when the Ford administration killed subsidies to the TTC and rent-geared-to-income housing. The willful ignorance towards residents’ struggles coupled with a reduced, weakened city council, is a “disabling” of democratic institutions, Sewell contested.

Eggleton, who was the longest-sitting mayor of Toronto for 11 years, also critiqued the provincial agenda. While the legislation is clearly stated to address the housing crisis in the city, he pointed to a lack of specificity in these goals. “What kind of housing are we talking about?” he asked, further explaining that the city is in an affordable housing crisis, and legislation needs to be able to reflect that regardless of provincial goals.

David Miller, who ended his term as mayor in 2010, said “there’s a magic in municipal government that isn’t present in provincial and federal governments.” He stated that this comes from the partnership between residents, the council, and the mayor. It saddened him to say that the new act is a “ward that disempowers engagement.”

The panel fully agreed that despite their opposition, it is still within the municipalities power to interpret the legislation. Therefore, residents, councils, and mayors alike should not act disempowered. Instead, we should continue to engage and put faith in our democracy because that is what decides the limits of our city.