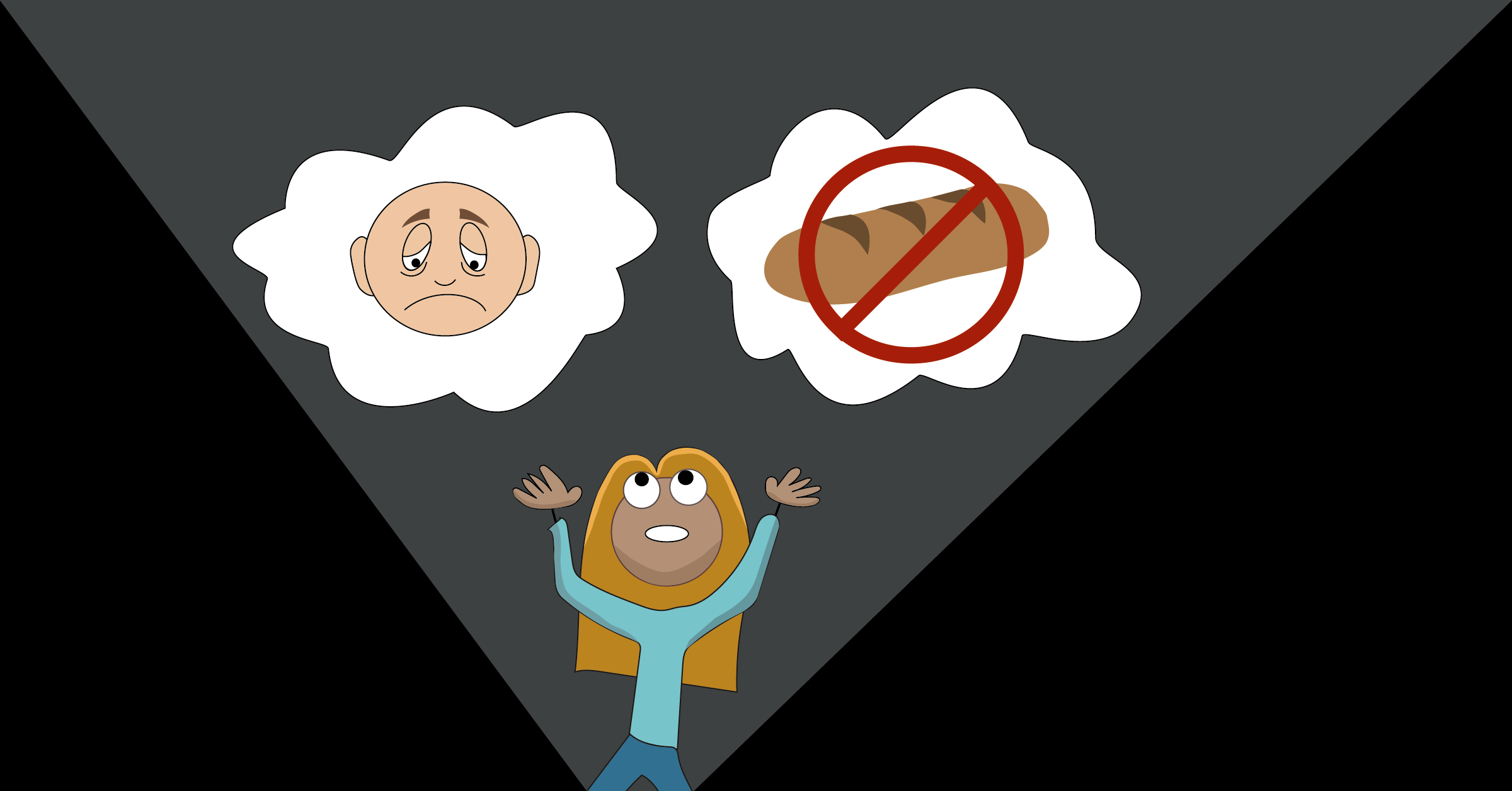

At first glance: Gluten tolerance and its misleading presentation

Many people who ingest the powdery protein mixture get sick by doing so and don’t even know it.

Gluten is a low-carb combination of protein substance from wheat, rye, and barley. It’s commonly an ingredient in flour that bakers rely on to make their dough stick together and rise when it’s baking.

Foods that contain gluten include pasta, beer, salad dressings, and, of course, baked goods. Even close-to-the-mouth topical products like lipstick and toothpaste contain gluten that can, as the Celiac Disease Foundation suggests, “unintentionally be ingested.” Some people struggle to digest gluten and experience in turn headaches, diarrhea, constipation, stomach aches, and joint pain.

Mental and emotional ramifications include all-encompassing fatigue, brain fog, and apathy—symptoms that society sometimes treats as exclusive to depression, especially if you’re a university student. What we eat or don’t eat influences the prevention and management of infirmities, and also triggers illness and subsequent psychological stress.

Gluten intolerance overlaps between three medical disorders. One, known as celiac disease, is largely accepted as an autoimmune disorder caused by a genetic predisposition to permanent gluten sensitivity. When individuals with celiac disease ingest gluten, their immune systems mistakenly destroy villi in the small intestine.

Villi are small structures that coat and expand the small intestine’s membrane and help the body regularly absorb nutrients. In other words, those with celiac disease are at greater risk of malnutrition. Alongside mood changes, manifestations of undernourishment, and disruptions in digestion, celiac disease may lead to more serve outcomes like infertility and anaemia.

The second disorder is wheat allergy. According to the Government of Canada, wheat is a food allergen that causes gastrointestinal discomfort like celiac disease, but also presents its own unique characteristics—skin issues and impediments to breathing are signs of a serious allergic reaction.

Last of all, non-celiac gluten sensitivity (NCGS) shares a similar symptom profile to celiac disease with the difference between them being: 1) NCGS sufferers recover faster when they stop eating gluten-containing foods, 2) NCGS doesn’t cause intestinal damage like celiac disease, and 3) both conditions are diagnosed differently.

Celiac disease is detected in two steps. First, doctors will order blood tests. If the results are positive for celiac disease antibodies, an endoscopy may follow to check for damaged villi. An endoscopy is a nonsurgical procedure wherein a flexible tube affixed with a light and camera examines a person’s digestive tract. If celiac disease and wheat allergy aren’t diagnosed, doctors will ask their patients to eat gluten-free foods over a period of time to assess for NCGS.

In a recent Harvard Health blog post, contributing editor Dr. Eva Selhub advises her readers on nutritional psychiatry: “Start paying attention to how eating different foods makes you feel.” Rather than attributing depressive thoughts and feelings to a neurochemical imbalance that needs to be drugged, the first question we might ask is, could this perhaps be a problematic diet masquerading as depression?