Valley of the Birdtail: How racism changed the experiences of two communities separated by a valley

In their new book, a U of T law graduate and an associate professor in the Faculty of Law highlight the inequalities affecting children in schools on reserves.

In Canada, over 110,000 school-aged children live on reserves. According to a report published in 2018, only 44 per cent of First Nations who lived on reserves between the ages of 18 and 24 had completed high school. In contrast, the same metric applied to only 88 per cent of other Canadians.

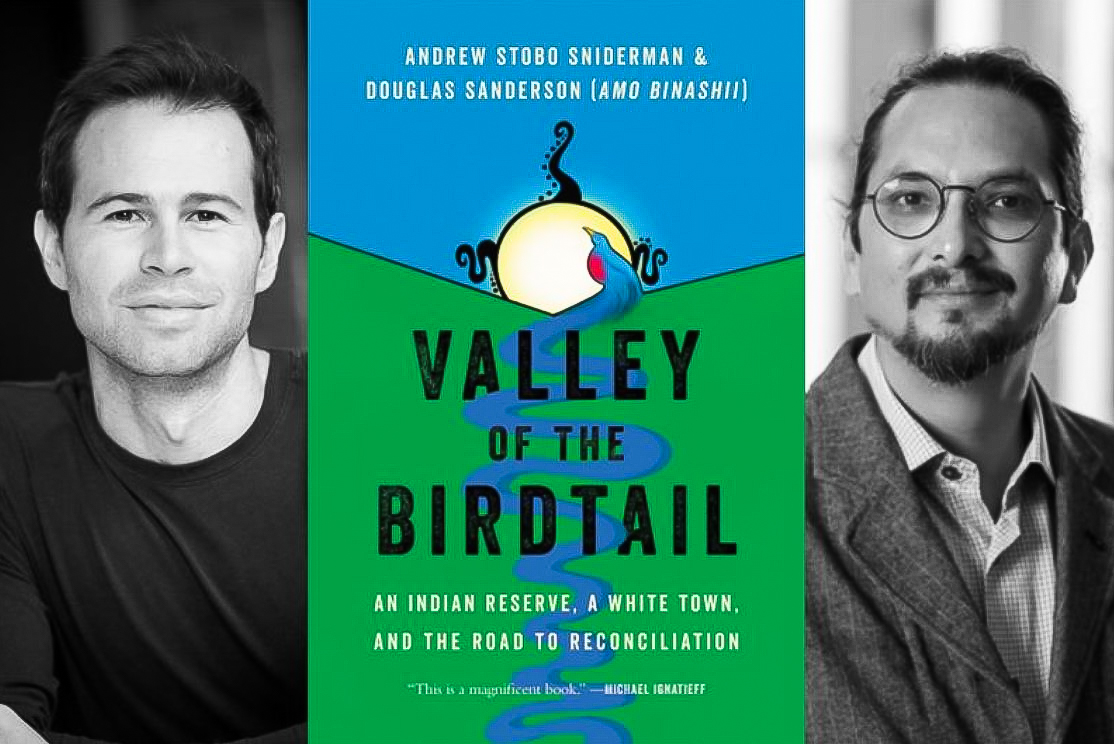

After learning about the inequalities that affect schools on reserves while pursuing his Juris Doctor at U of T, Andrew Stobo Sniderman, a lawyer and a Rhodes Scholar from Montreal, started researching the disparities that led to these systemic deficiencies. “I found out that Indigenous students all across Canada were 40 to 50 per cent underfunded per student, compared to students in provincial public schools. As a law student, I couldn’t understand how that was legal,” recalled Stobo Sniderman. He reached out to Associate Professor Douglas Sanderson (Amo Binashii) to collaborate on a book titled Valley of the Birdtail: An Indian Reserve, a White Town, and the Road to Reconciliation. Released in August 2022, the book is about two communities separated by a valley: Waywayseecappo, a reserve in Manitoba, and a neighbouring town called Rossburn.

During a presentation as part of The Jackman Series at U of T’s Faculty of Law on November 22, 2022, the authors recounted the process of putting the book together, meeting with residents on reserves, and hearing their stories. “It is more ambitious than just a story about the education inequality,” explained Stobo Sniderman. “It’s about how this inequality developed between these two communities over the last 150 years across many domains.”

The book follows multiple generations of two families. In Rossburn, a town once settled by Ukrainian immigrants who fled poverty, family income is near the national average and most adults have completed a university degree. Just across a valley, in Waywayseecappo, families live below the line of poverty.

Residential schools started opening in Canada as early as the 1880s. Indigenous children were taken from their parents and brought to schools so that nuns and priests could transform them into their definition of proper, exemplary individuals. Later, in the 1950s and 1960s, the “integration” era happened when the federal government decided to send students from reserves to provincial public schools to assimilate Indigenous Peoples into the dominant society’s norms.

Finally, in 1971, the Manitoba Indian Brotherhood released a manifesto that demanded an end to integrated education because it had no relevance to Indigenous culture and lifestyle. Put under pressure, the government agreed to give the First Nations communities control over their school education. This led to the current schooling systems where reserve and local schools remain separate, and reserve schools are funded by the federal government, and not the provincial government.

In his interview with CBC, Evan Taypotat, Chief of the Kahkewistahaw First Nation, stated that “The First Nations schools are looked after by someone in Ottawa, who [couldn’t] actually care less about what’s going on on the reserve. The average funding for a reserve kid is about $6,800. The funding for a kid in Broadview, which is about 10 minutes away, is $11,000.”

While increased funding may seem like a logical solution, Professor Sanderson believes “it’s never going to cut it,” because the inequalities go further than just the educational system.

“There’s a couple of documents that we printed out in the book that I had trouble believing. I had to see them for myself to believe they even exist,” continued Stobo Sniderman.

One of the documents the authors found details permission requests from a federal agent to a father that allows him to leave a reserve to go visit his son at a residential school. Another document is a permit from a government agency for someone living on reserve to sell a load of barley to someone from outside of the reserve. Documents like these had to be issued because of the restricting laws passed in the 19th and 20th centuries. For instance, when the residential school system was operational, parents were often denied any contact with their children in the schools. In the late 19th century, The Indian Act banned traditional Indigenous functions including the potlatch, ghost dance, and sun dance, with police arresting Indigenous Peoples for performing ceremonies that were part of their culture. And in 1927, another law was passed forbidding Indigenous Peoples from hiring any legal representatives or seeking legal counsel. These are only a few of the restrictions communities on reserves faced throughout the years. Even though these laws are not presently in effect, Indigenous Peoples still lack independence and equal treatment.

Both Stobo Sniderman and Professor Sanderson believe that the way to resolve many of these injustices is to provide Indigenous Peoples with governing authority over their land. Communities that live on reserves need to make decisions about funding for schools and healthcare for themselves. “We know that if Indigenous governments were empowered to raise and spend money, their child welfare system would be well-functioning,” maintained Stobo Sniderman. The authors hope to change the way readers think about Indigenous education and understand the role of law in finding solutions.

Thank you, Olga, for this thoughtful piece.