How do we react when those we care about act unethically?

PhD candidate Rachel Forbes studies the importance of upholding moral standards and why we are less harsh on our loved ones.

As an inspiring journalist, I hold a set of ethical and moral codes: write with integrity and truth when sharing a message with the public. No matter what field you are in, there are moral codes required to uphold professional standards. Even in our personal lives, we set boundaries and hold ethical values, although, these are often not synonymous with those outlined by our professions. But what happens when people we care about cross those boundaries? Rachel Forbes, a PhD candidate at the University of Toronto, evaluates that personal struggle by asking: what do you do when someone you love crosses your ethical boundaries?

Forbes completed an Honours Bachelor of Science with a Psychology Research Specialist in 2017, and a Master of Arts in Psychology in 2018—both earned from U of T. Forbes worked as a teaching assistant for different courses in the Department of Psychology, and under the supervision of University of Toronto Mississauga professor Jennifer Stellar, Forbes is expected to receive her PhD in Psychology by the end of the year.

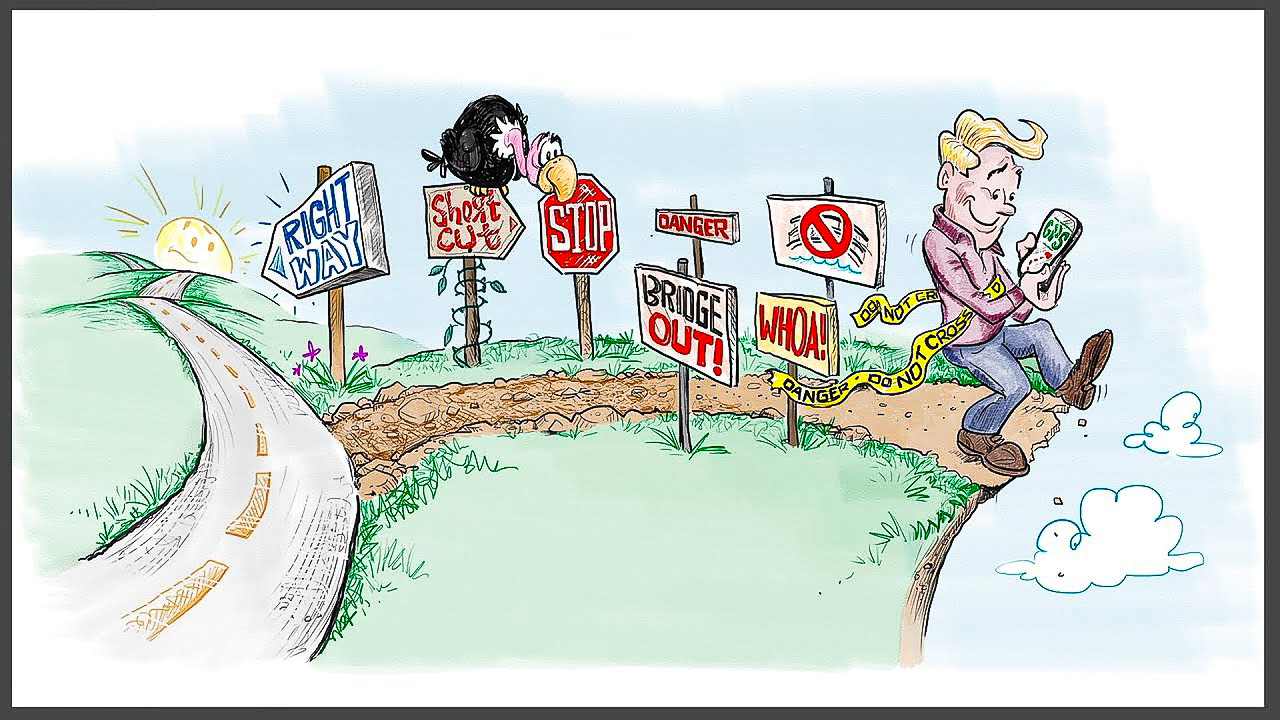

Forbes published her article “When the Ones We Love Misbehave: Exploring Moral Processes within Intimate Bonds” in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology: Attitudes and Social Cognition. In her research, Forbes discusses how we react when our loved ones do something unethical. To develop and implement our ethical codes, we rely on our grasp of morality—a code of conduct often described as the self’s perception of what’s right or wrong. It could be thought of as the common imagery of having an angel and devil on your shoulder, guiding you through decisions.

Forbes’ research stands out among the abundant studies on morality for its unique viewpoint—rather than focusing solely on morality in the context of strangers, she considers people’s moral responses to unethical actions performed by those they care about. As a hypothesis, Forbes predicted that the emotional response of individuals would be significantly less negative toward transgressors with whom participants have a personal connection, and more negative toward the unethical behaviours of strangers.

Forbes’ research was conducted over four independent studies. In the first, Forbes collected data from 207 participants who were in a romantic relationship for a minimum of one year. She studied the participants’ reactions to three hypothetical situations—each designed to be immoral, and each involving a different transgressor: a romantic partner, a friend, or a stranger. To understand each participant’s opinion on the hypothetical acts, all participants were asked to rate how unethical they believed each act was on a scale of one to seven, where one was “not unethical,” and seven was “very unethical.” For example, a participant could have been asked to rate the ethicality of their romantic partner committing theft, lying about having paid a bill, or starting a rumour. Results of the study favoured Forbes’ hypothesis, demonstrating that participants showed stronger negative responses to strangers, and tended to be more lenient toward individuals they had intimate bonds with.

The second study served to replicate similar results from the first study by asking nearly 500 participants to recall both a time when people in their lives had done something morally wrong, and one when strangers misbehaved instead. Participants were then asked to attempt to reason as to why each person had chosen to do something unethical, and then rate their acts on the same scale as the first study. The results demonstrated trends similar to those from Forbes’ first study.

Because the second study asked participants to recall an event that happened in the past, Forbes identified a potential for retrospective bias—our tendency to recall past events and their frequency inaccurately. So, the third study aimed to eliminate this factor by asking participants to report daily unethical acts experienced with strangers, romantic partners, coworkers, and friends over 15 days. Unsurprisingly, participants reported that their loved ones had conducted many more unethical acts than strangers. However, as Forbes predicted, participants reported feeling less angry towards their friends and romantic partners for committing immoral actions as compared to strangers.

The final study asked participants to bring a romantic partner, friend, or acquaintance with them. The subjects were then asked to reveal to each other unethical decisions they had made in the past. Forbes provided each participant with a survey that suggested that the other had done something unethical. The participants had to rate themselves and their partners on an ethical scale similar to that from studies one and two. Forbes’ study revealed that participants were less critical of their loved ones, but more critical of themselves in their morality ratings, supporting Forbes’ original hypothesis.

Over the course of these four studies, Forbes was able to identify that there is, in fact, a difference in the ways that people perceive immoral acts done by their loved ones versus those by strangers. Forbes also noted that this watering down of our moral responses could be our way of safeguarding our relationships. An interesting finding demonstrated that individuals felt some embarrassment or emotional burden when thinking of their loved ones as acting unethically. Thus, in trying to protect the intimate bonds we share with people, we end up translating the burdens of their transgression onto ourselves.

Associate Features Editor (Volume 48 & 49) — A recent graduate from UTM, Dalainey is currently working on completing her post-graduate studies in Professional Writing in Ottawa. She previously served as Staff Writer for The Medium‘s 47th Volume and as Associate Features Editor for Volume 48. Through her passion for languages, Dal hopes to create a fun and inviting atmosphere for readers through her contributions to the paper. When she isn’t working, Dal focuses on developing digital art and writing her first novel. You can connect with Dal on her Instagram or LinkedIn.