A student’s worst nightmare: Writer’s block

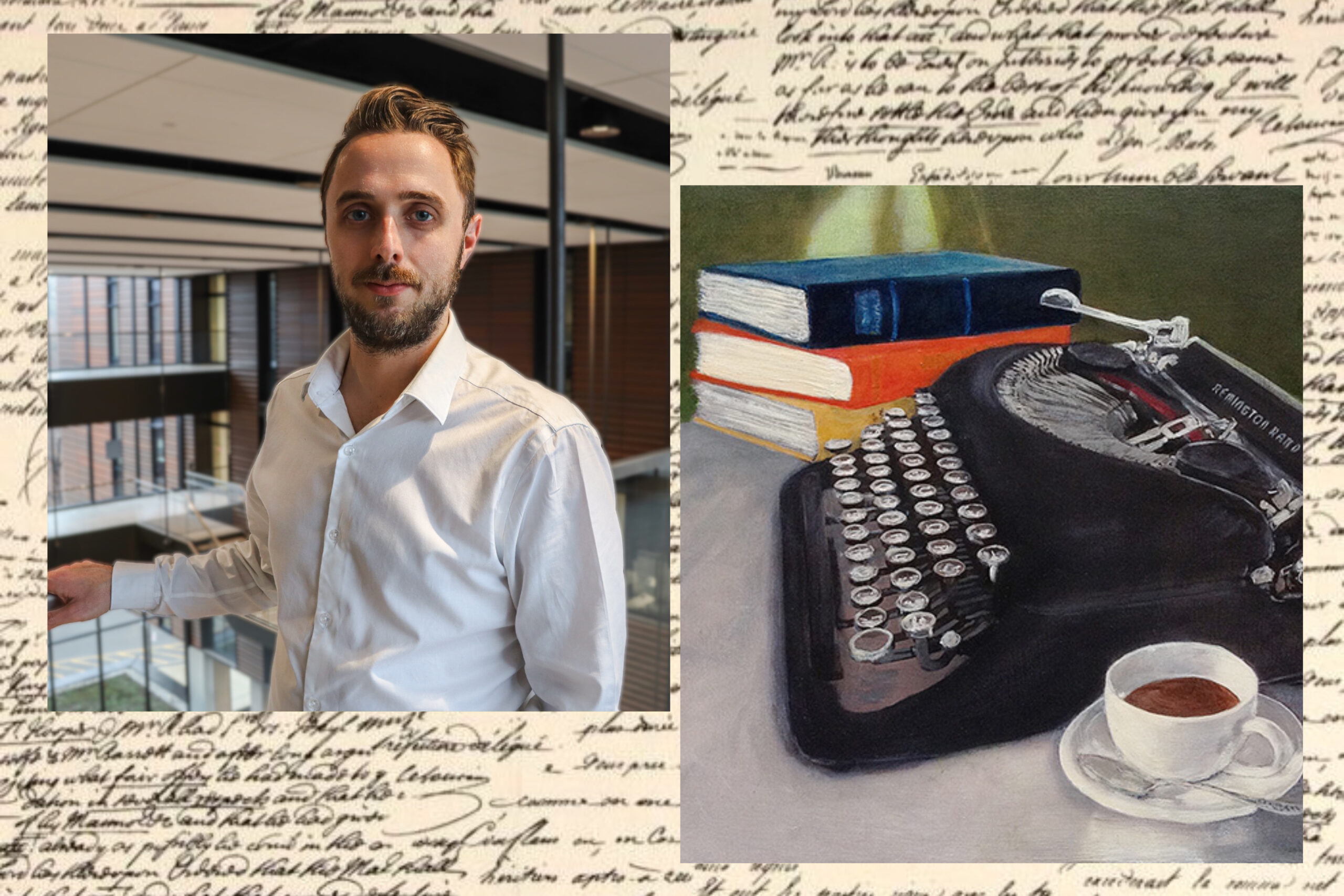

Professor Christopher Eaton discusses his doctorate research and tips on how to overcome writer’s block.

The transition from my small suburban high school to the packed halls of the University of Toronto Mississauga (UTM) is one that I will never forget. I had no idea I would be assigned my first university-level essay within my first week of school, but I didn’t care. I loved essays—until I sat down to write one. A blank stare at a Word document with only my name and course code welcomed me into university. I was hit head-on with an unfortunate affliction: writer’s block.

Christopher Eaton, an assistant professor at the Institute for the Study of University Pedagogy at UTM, is currently teaching a first-year writing class at UTM, ISP100: Writing for University and Beyond. Professor Eaton, along with other professors in the writing stream, teach students how to identify the signs of writer’s block and how to move past them. The course additionally gets students accustomed to academic writing at the university level and beyond. Next academic year, Professor Eaton will teach a course on science communication. The course will explore how various means of scientific dissemination can either benefit data or skew data through the way it is communicated.

Writer’s block is the process wherein writing is stagnant in its developmental stage. In order to move forward, writers need to not only accrue more knowledge, but actually process it, make it their own, and translate it into writing. “Now the challenge becomes,” explains Professor Eaton, “that people don’t know, not even just where to start, but how to form a thought in the paper in a cohesive way.” That can be the result of not having enough time to do the processing work or not having developed the ability to find the information needed. “They know how to find portions of the information, and they’re forming their thoughts on partial conversations in the literature, but they haven’t read the whole scope,” elaborates Professor Eaton.

Professor Eaton completed his undergraduate degree in English Literature and French at Wilfred Laurier University before pursuing his Master’s in English Rhetoric and Literature at the University of Waterloo. In both institutions, Professor Eaton worked at their writing centres, where he developed a passion for language and began asking questions about how people learn to write. “I was able to start thinking about writing; how people learn to write and how they transfer skills from one context to another—how they pick up on certain skills and adapt them in unique ways,” explains Professor Eaton.

Completing his PhD in Education at Western University, Professor Eaton’s doctoral research looked at the ways that writing is taught from the perspective of people who are going to be teaching students everywhere from Kindergarten to Grade 12. “These [teachers] are accomplished. They have an undergraduate degree. They’re moving into professional practice and they’re struggling with a very fundamental concept that they’re going to have to help students work their way out of in the classroom,” explains Professor Eaton.

Additionally, Professor Eaton focused his doctoral research on how students develop writing skills and the student perspective on writing. “I wasn’t looking at it from the instructor’s perspective or what the best practices are, but rather how students are interacting with those practices,” explains Professor Eaton, “In most cases, we were looking at why students are so resistant and why there might be a change in that attitude by the time they finish their mandatory first-year writing courses.”

“Students would tell us that they know what they want to say, but don’t know how,” explains Professor Eaton. “We took a step back to look at the literature and we started asking ourselves, well, ‘what are they actually saying?’” At that time, Professor Eaton concluded that students don’t really know what they’re trying to say; they are still processing the information they need to write about.

Unfortunately, the solution to writer’s block isn’t always one a student is willing to hear: you need to be prepared. “Staggering your work with outlines and drafts helps prevent writer’s block,” explains Professor Eaton, “although I know that’s not always possible in a busy semester.” Outlines can help you work through your notes, readings, and research to further process the information you trying to put out. “When we’re learning something new, we have an introductory period where we’re starting to just really process the ideas for the first time,” argues Professor Eaton, “And that’s normal and part of the learning process.” Get more information, do more research, get a deeper understanding of the concept, and you’ll slowly be able to translate that thinking into a rounded product. So rather than focusing on being stuck, acknowledge that being stuck is a normal part of the thinking process. Push through the writing hump, because after all, writer’s block is a rite of passage for all university students.

Associate Features Editor (Volume 48 & 49) — A recent graduate from UTM, Dalainey is currently working on completing her post-graduate studies in Professional Writing in Ottawa. She previously served as Staff Writer for The Medium‘s 47th Volume and as Associate Features Editor for Volume 48. Through her passion for languages, Dal hopes to create a fun and inviting atmosphere for readers through her contributions to the paper. When she isn’t working, Dal focuses on developing digital art and writing her first novel. You can connect with Dal on her Instagram or LinkedIn.

This article does a great job outlining the writing process and where the common struggles come from. Professor Eaton’s perspective on the topic makes for an interesting discussion and he provides great solutions. Oftentimes writers block is just not knowing how to put the idea on the page or needing to think a bit more. In my experience even something simple like listing out what each point or section will entail can be beneficial since it helps you think deeper about your points and lead you in a clear direction.