Dennis Lee and No Pain Like This Body

The Canadian writer talks about his editorial work on the book with personal remembrances of its author, Harold Sonny Ladoo.

In the spring of 1967, Dennis Lee, a Governor General’s award winner for English-language poetry, co-founded House of Anansi Press. Anansi has since become a leader in independent Canadian publishing, recently debuting novels by the likes of acclaimed writers Johnathan Garfinkel and Katherena Vermette. In its early days, however, the publisher was, in the words of Lee, “more of a shambling crusade” than a company.

“Dave Godfrey and I decided to [self-publish] my first poetry collection, ‘Kingdom of Absence’ […] Things could easily have stopped with that, but instead we took another step forward in the fall: doing a second printing of Absence, plus a reprint of Margaret Atwood’s first book, The Circle Game, plus a collection of Dave’s stories, Death Goes Better with Coca Cola,” Lee explains. “The only goal or vision for Anansi was that it would be a writers’ press, where literary quality was the most important thing.”

In keeping with the spirit of that vision, Anansi accepted a manuscript of the enduring novel No Pain Like This Body by late Caribbean writer and University of Toronto Mississauga (UTM) graduate of English Literature, Harold Sonny Ladoo. With Lee as its editor, the book was published in 1972. “When Harold submitted No Pain, it both looked not at all like anything we’d published up till then, and at the same time, it fit in perfectly—a passionate, ground-breaking novel by an exciting, one-of-a-kind new writer,” shares Lee.

No Pain Like This Body, one of Ladoo’s two published books, gives readers a sense of Trinidad’s history of indentureship and the near-slavery, poverty, and trauma that it would bring many East Indians—including, as we can only speculate, the socially conscious author himself. “I saw that you made one more among us, dragging old / generations of pain as perpetual fate and landscape, bound / to work through it in words; / and I relaxed,” writes Lee in his elegiac poem named The Death of Harold Ladoo.

In 2022, The Medium published an article wherein I briefly chronicle the life and work of Ladoo. Reading it will tell you that Ladoo arrived in Toronto in 1968 as, like Lee says, “a poor but ambitious immigrant.” Around that time, a spontaneous meeting with Peter Such, former writer-in-residence at UTM (then known as Erindale College), afforded Ladoo a post-secondary education.

Under Such’s guidance, Ladoo and his writing would see transformative change. Seemingly overnight, he went from being a rather ineffective Victorian-inspired poet to a one-to-watch-out-for fiction writer. But Ladoo had a short-lived career. He returned to his home island of Trinidad in August of 1973 only to be murdered over presumably a familial property dispute. The case of his death remains officially unsolved.

“I don’t remember how I first heard about it, but I do recall being stopped dead in my tracks,” Lee says regarding the moment he received news of Ladoo’s death. “I remember listening to a tribute to Harold on the CBC, some months later, and being moved by the East Indian music they played,” he adds. Lee shares that he managed to get a copy of the record and frequently played it for a while afterwards to remember his “deeply serious, committed, [and driven]” friend.

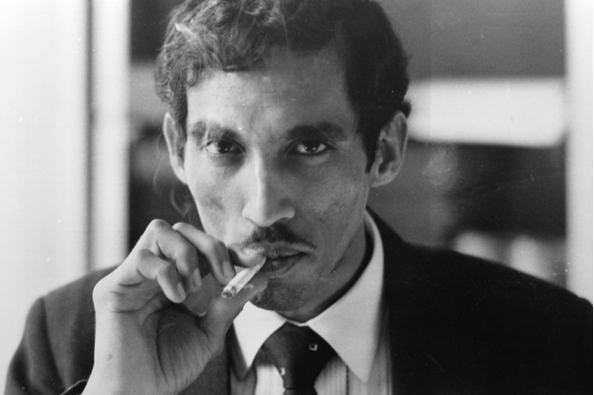

Lee met Ladoo in 1971 at a Toronto pub called The Red Lion, next to an Anansi office on Jarvis Street—a meeting that’s recreated in the opening pages of The Death of Harold Ladoo. “Was he bringing the manuscript in for the first time? Had I read it, and felt enough enthusiasm for the first draft to want to meet? I can’t summon back the details now—it was half a century ago—but the account of that first meeting in the poem is trustworthy—about what he looked like, and how he spoke,” Lee says. “Very thin, deferential at first, then a mounting intensity that became charismatic.”

When asked about the editing process for No Pain Like This Body, Lee responds: “[Harold] didn’t take orders from me, and I didn’t want him to. But I did challenge him on some things—particularly the structure of the book, I believe. His ear for the creole dialect the book is written in was already magical, and of course, that was all foreign to me. So, I had nothing to contribute in that area—and nothing was needed […] I remember a sense of mounting excitement as we worked on it and he did some amazing revision, and the thunderclap power of the story got freed up.”

Ladoo dedicated “No Pain Like This Body” to Shirley Gibson. At the time of the novel’s release, Gibson was the estranged wife of Graeme Gibson, a celebrated Canadian novelist who was then engaging with Margaret Atwood, his partner until he died in 2019. “Shirley was the ‘Office Manager’ of our tiny staff, and she could be very warm and competent, so she was sort of the den mother of this makeshift, off-balance little enterprise when Harold hooked up with us,” Lee recalls. “I imagine she helped him with some of the questions and amenities that a newcomer would need.”

In 1974, Anansi posthumously published “Yesterdays,” Ladoo’s second novel—a rage-fuelled comedy exploring the effects of Canadian mission work on East Indian indentured labourers. By then, Lee had left Anansi and stayed sporadically in touch with Ladoo. “My next main engagement with him would be writing ‘The Death of Harold Ladoo’ several years later,” he says. “It turns out that the initial, self-appointed task—of writing a standard-issue elegy of praise and grief, like a speech at a funeral or a memorial service—is papering over a much more complex relationship to the deceased.”

The poem opens with an articulation of deeply buried feelings that enter the speaker’s consciousness through an explosion of grief. Initially expressed in over-the-top and savage statements that actually don’t have any destructive power, the speaker’s pain is sometimes misread to the detriment of not only Harold’s character, but also the two’s relationship and the environment in which they met.

“To zero in on one of these initial, over-the-top expressions of anger or disillusionment, and declare it to be what Lee ‘really thinks’ of Harold Ladoo, or the Anansi years, or himself makes for good tabloid copy, but completely misunderstands what’s going on in the poem,” Lee says. “There are these heavy-duty pendulum swings of feeling in the course of the elegy, but their overall effect is to arrive at a richer place of understanding […] The speaker comes to accept that Harold had serious flaws as well as extraordinary virtues—and the world doesn’t come to an end,” he explains.

The latest revision of The Death of Harold Ladoo can be found in Heart Residence (2017), a collection of poems by Lee.