Speedrunning’s popularity shows no signs of slowing down

Exploring the evolution of a community capable of raising $3.4 million for charity in one tournament.

What started on a 1980 Atari 2600 video game called Dragster now captivates millions of people worldwide—speedrunning. The goal is simple: complete the game as fast as you can. Nearly every single-player video game in the world has a speedrunning record attached to it.

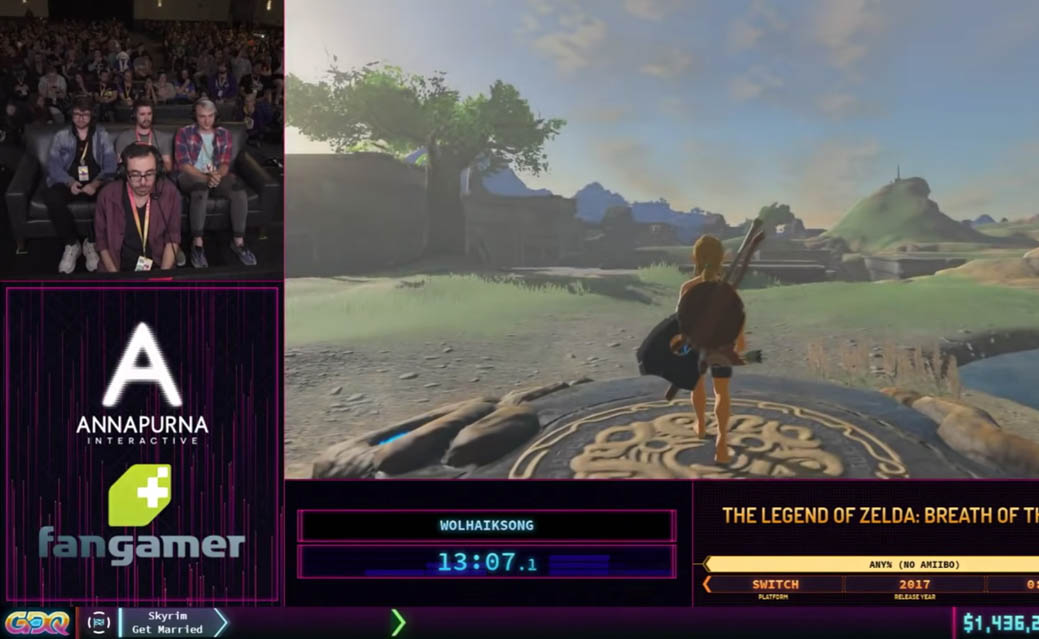

In 2019, a speedrunning tournament called Summer Games Done Quick raised $3,032,114.62 for Doctors Without Borders, a humanitarian organization. The marathon consisted of hundreds of players competing across hundreds of games. For 2022, Awesome Games Done Quick (AGDQ)—a bi-annual fundraiser that ran from January 9 to January 16—raised $3.4 million for the Prevent Cancer Foundation.

So, what is speedrunning?

The video game that kick-started speedrunning’s popularity was id Software’s Doom (1993). In the game, players assume the role of a space marine as they fight through hordes of demons invading from hell. The original game had nine levels that players needed to beat sequentially.

What set Doom apart was that it had a timer embedded in the game, setting your time against a par time—or a “time to beat.” It allowed players to record video files that they could watch, study, and share with others. Players could publish their achievements on online forums. Evidence of a record was no longer reliant on a blurry screenshot of a timestamp, now there was video proof.

The use of video files not only lent credibility to players’ achievements, but because the game’s mechanics were complex enough to encourage creative strategies and competition, being able to watch someone else’s speedrun helped propel the community forward.

Beneath this was an underlying philosophy: speed is equal to skill. Anyone could complete a level in Doom if they were given the rest of their life, and the nature of video games allows them just that. But to complete the level with perfect execution at a speed that no one else had achieved, now that is the challenge.

Across all forms of elaborate achievement-driven competition, those who distinguish themselves from their peers are not just fundamentally stronger, faster, or smarter, but they also approach the challenge like no one else before. Speedrunning demands this, and that is why it continues to captivate audiences. It generally does not matter how you do it as long as you are the fastest.

As the internet and video games evolved through the 1990s, chat boards and forums became clubhouses where players could theorycraft—find prime strategies through mathematical analysis—and admire the achievements of others. Pretty soon, games like Metroid, Mario Kart, and Perfect Dark had hundreds of players competing in speedruns.

Speed Demos Archive, a website founded in 1998, created a virtual space where players could publish their recordings and discuss strategies. It consolidated a community that was previously spread across dozens of different forums and websites. The website opened the door for speedrunning to expand to games that had not been previously challenged, and the community flourished.

In 2005, YouTube gave speedrunners the platform the community was waiting for. Suddenly there was an intuitively designed website where players could upload more than just their record-breaking runs. Now, players could document their progression toward breaking a record by documenting all the work that went into it. They could showcase their strategies, publish their calculations, and demonstrate their triumphs. This was an important development in speedrunning’s popularity because it emphasized the how. What captivates the attention of fans is not so much the timestamp that legitimizes a record but rather the strategies the player used.

As YouTube was not reserved for speedrunning, it helped draw a wider crowd toward the challenge because it exposed speedrunning to people who would never have come across it otherwise. When the streaming platform Twitch was released in 2011, viewers could now witness the time and effort that went into setting records live. It also helped monetize speedrunning so that players could make a living off what they spent so much time doing. This monetization also attracted sponsors and helped catapult the gaming community to where it is now; to where it can raise $3.4 million for the Prevent Cancer Foundation.

Today, players compete across a variety of different games and categories in speedrunning tournaments all over the world. Some people attempt to speedrun a game blindfolded or compete against another to see who can do it the fastest.

AGDQ is set to have its next fundraising event, Frost Fatales, from February 27 to March 5. It is an all-woman speedrunning event that will raise money for the Malala Fund, a charity that aims to bring education to women across the world.

Copy Editor (Volume 49) | aidan@themedium.ca —Aidan is completing a major in Professional Writing and Communications at the University of Toronto Mississauga. He previously worked as the Associate Editor for the Arts and Entertainment section of The Medium, and currently works as the Copy Editor for The Medium. When he’s not catching up on course work or thumbing through style guides, Aidan spends his free time exercising (begrudgingly), singing (unmelodically), and trying (helplessly) to read David Foster Wallace’s Infinite Jest. The latter of which has taken 3 years to reach the 16th page. You can connect with Aidan at aidan@themedium.ca.