Conventions and Inventions in Blood Quantum

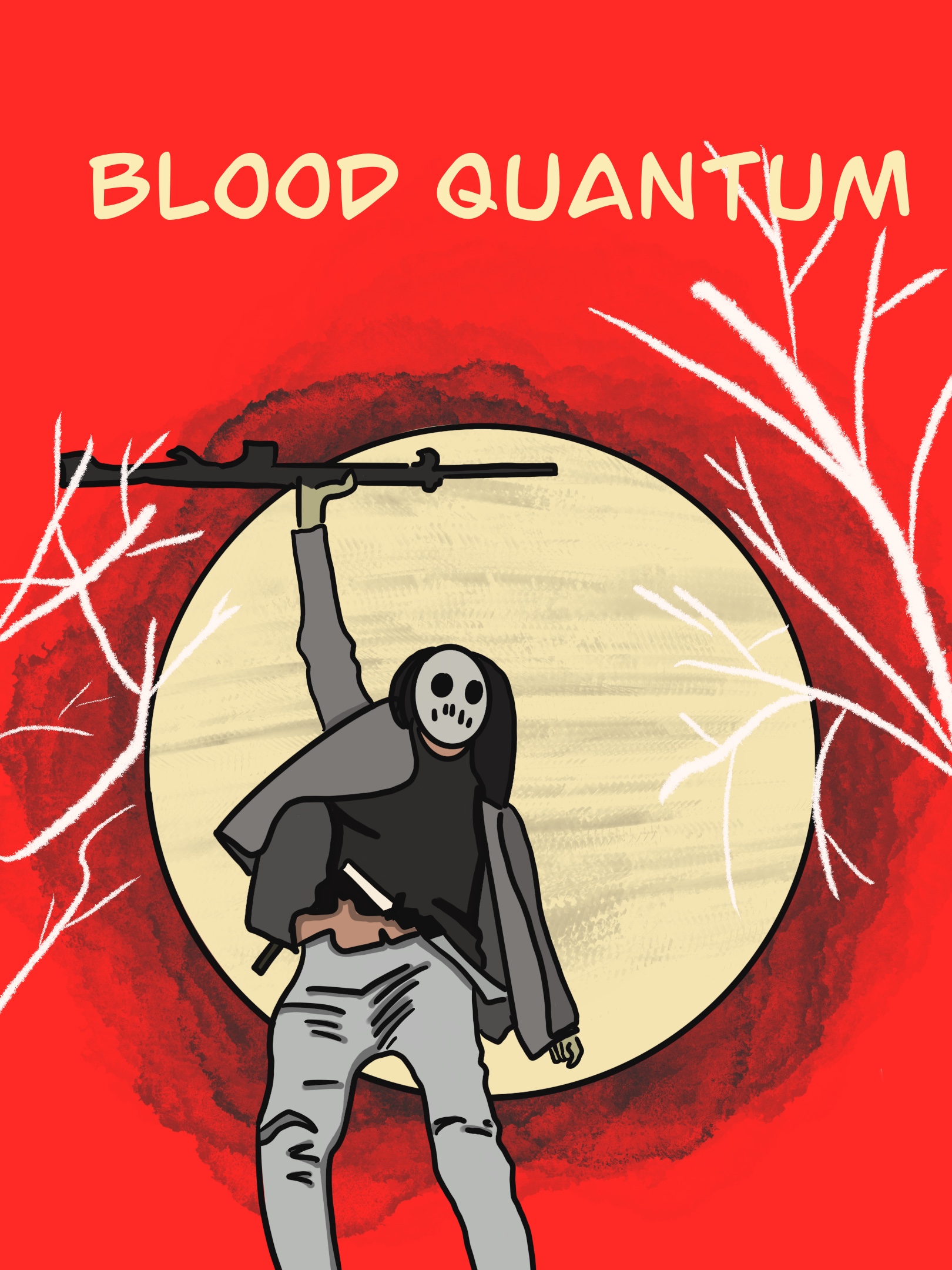

Jeff Barnaby’s 2019 zombie film reimagines the Hollywood western.

Early in the epoch of Hollywood film, Indigenous men were presented as the stoic, fearless warrior—brave and silent. When the western genre shifted towards its modern conventions and began portraying Indigenous Peoples as violent and uncivilized, these redeemable qualities were redistributed onto the white male protagonist—the John Waynes.

Jeff Barnaby’s 2019 film Blood Quantum, however, challenges these conventions and

reimagines the narrative space of the Hollywood western as being capable of expressing an Indigenous narrative in a post-colonial landscape. Barnaby deconstructs these genre conventions and criticizes their stereotypes by incorporating them into an Indigenous narrative—one directed by an Indigenous auteur and starring indigenous actors. The film, in consequence, is self-determined.

As an Indigenous director, Barnaby brings his own accent and expressions to the language of the western film. He sticks close to the script but changes the context in which the film operates. Most notably, he blends the popular Hollywood genres of horror into his western story. The plot of the film revolves around an isolated Mi’kmaq reserve of Red Crow who are curiously immune to a zombie plague that infects the outside world. Barnaby confronts, critiques, and reorganizes dominant narratives to privilege an Indigenous perspective in a post-colonial landscape on screen.

The setting is reimagined from the American plains to a post-apocalyptic coastal setting; the colony—typically spatially and physically threatened by some sort of encroaching danger—is changed from a group of “settlers” to an indigenous community; and the threat reimagined from Indigenous peoples to zombies. The brave, sharp, emotionally guarded “cowboy” is also changed, from John Wayne to the chief of the Mi’kmaq people. These deviations from the western blueprint deterritorialize the genre and reimagine it as capable of including Indigenous voices and perspectives.

There are several scenes that pronounce this but one that caught my attention comes just a few scenes into the second act. A scene opens with a birds-eye shot that frames an old map laid out across a table. The shot transitions to a low angle, “cowboy shot” as Traylor, played by actor Michael Greyeyes, traces the perimeter of the camp, briefing the two beside him on the threatened sections. This sort of scene is characteristic of western films and usually comes before the big showdown, as the male protagonist draws up his plan and takes control of the townsfolk, telling them where to be and what to do and most importantly, “to wait for my signal.”

In Barnaby’s film, the reservation stands in for the colony, the cowboy is reimagined as a chief, and the zombies become the “savages.” These changes work to create the Indigenous western, a reimagined genre that gives a voice to Indigenous Peoples to tell their own story and critique the way their story has been told in the past.

Copy Editor (Volume 49) | aidan@themedium.ca —Aidan is completing a major in Professional Writing and Communications at the University of Toronto Mississauga. He previously worked as the Associate Editor for the Arts and Entertainment section of The Medium, and currently works as the Copy Editor for The Medium. When he’s not catching up on course work or thumbing through style guides, Aidan spends his free time exercising (begrudgingly), singing (unmelodically), and trying (helplessly) to read David Foster Wallace’s Infinite Jest. The latter of which has taken 3 years to reach the 16th page. You can connect with Aidan at aidan@themedium.ca.