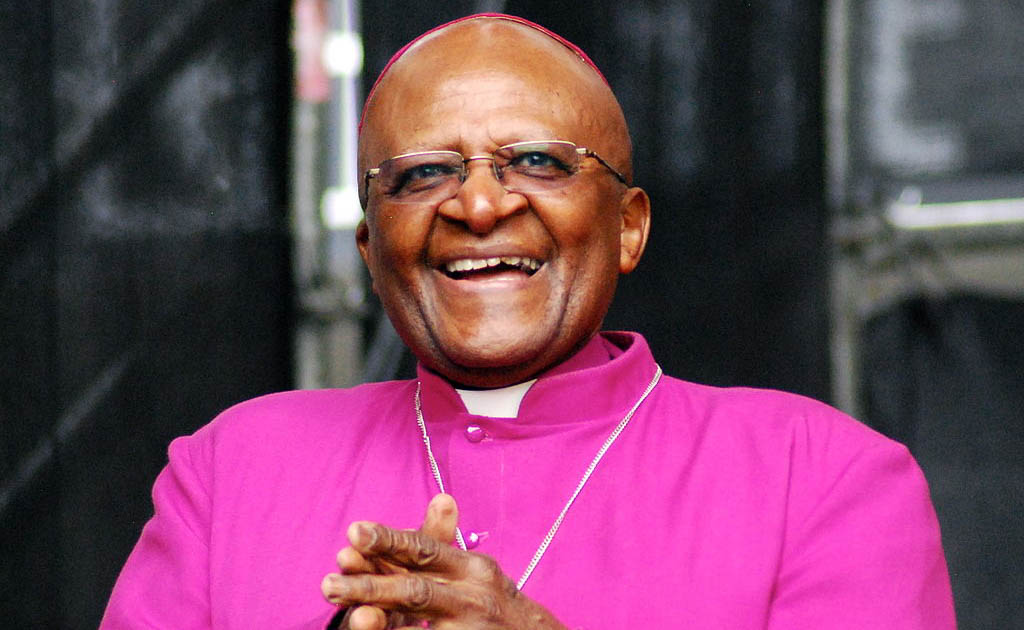

Remembering Desmond Tutu, the incomparable, fearless, and empowering warrior for freedom

In a world where systems of oppression still hold real power, South Africa became the blueprint for positive change

My earliest memory of the late Archbishop Desmond Tutu is more of a sensation. The sensation of quiet power.

I remember a short, purple-robed man speaking. My parents, uncles, and aunties gathered under the smell of black tea and the blue glow of a TV screen, transfixed. I watched them, their backs bending into question marks of prostration. My father looking at me, eyes shining, and saying, “That’s Desmond Tutu.” The archbishop, ‘The Arch’, a name as severe as it was comforting, like a balm of protection.

On December 26, 2021, just a few days before the new year, in a year in which so much had already been lost, the great and beautiful Lernaean beast of our African continent lost an irreplaceable head, and the world one of its dearest loves. Desmond Tutu was dead.

Tutu was born Black during South Africa’s apartheid, when one would eventually pay for that kind of crime, with their body, their time, or their life. I loved him first for his work in advocating against apartheid through the late 90s, a crucial effort in the destruction of the apartheid state. Most notably, he headed the Truth and Reconciliation Committee (TRC), a program designed to reconcile victims of apartheid and their aggressors. Uncovering over 22,000 stories, Tutu steered South Africa through painful, but necessary, recollection. He mediated as his nation looked its beast in the eye and threw its spear. Men and women, bodies still bearing the evidence of an insidious state, whose minds were still haunted and hunted by their pain, came face to face with the demons of apartheid.

Forgiveness seemed too much to ask, and yet it ignited a catharsis that spoke dark truths to power. The world, and South Africa, saw just how vast our possibilities were. To move forward, we must reckon with the past, open our old wounds, and cleanse them so that they won’t fester. In a world where systems of oppression still hold real power, South Africa became the blueprint for positive change.

In a Nobel Peace Prize interview in 1984, Desmond Tutu described a good leader as one who serves, who “leads for the sake of the led,” a position that he espoused as a lifestyle. Service. Giving himself to the causes of the good people, the little people, the voiceless and powerless, he became a moral archetype in Africa and the world over.

Long after his resignation he continued his advocacy. Tutu called for the boycott of Israel in 2014 after the shocking killings of Palestinians along the Gaza strip. He demanded U.S. President George Bush and U.K. Prime Minister Tony Blair be held accountable for their contributions to the Iraq war, and rebuked the wickedness of then Zimbabwean President Robert Mugabe, comparing him to a textbook stereotype of a corrupt African politician.

Tutu was unafraid of controversy within the church too, boldly supporting his daughter’s marriage to another woman in contention with the canonical beliefs of South Africa’s Anglican establishment and expressing a refusal to “go to a homophobic heaven” and worship “a God who is homophobic.” His humanism exceeded the hardness of dogma, a position the impact of which one can only imagine within the thick homophobic rhetoric of Africa’s majority.

The archbishop is gone. What happens now?

We honour him.

The main anti-hero of the play Death and the King’s Horseman calls memory “the chink” in death’s “armor of conceit,” an apt metaphor. We have memory, a primal blessing. Remember him, the archbishop. Remember the message in his posture, his philosophical ‘arch’ of modesty as armor and shield, a weapon more cunning than fury, and just as destructive. Remember how despite being a short man his voice rang high, his presence brushing against the heavens, tickling the feet of God with the height of his moral gumption. I will remember his vestments, purple in color, the color of open wounds and fresh bruises, the same color of wounds and bruises as they heal, the color of pain shared, and pain being taken away. I will remember what he meant to me, a troubled teen struggling with his place in the world and his own identity. He told me to be brave for the little person inside me. Memorize him and who he was to you, to Africa, to us.

Amen.