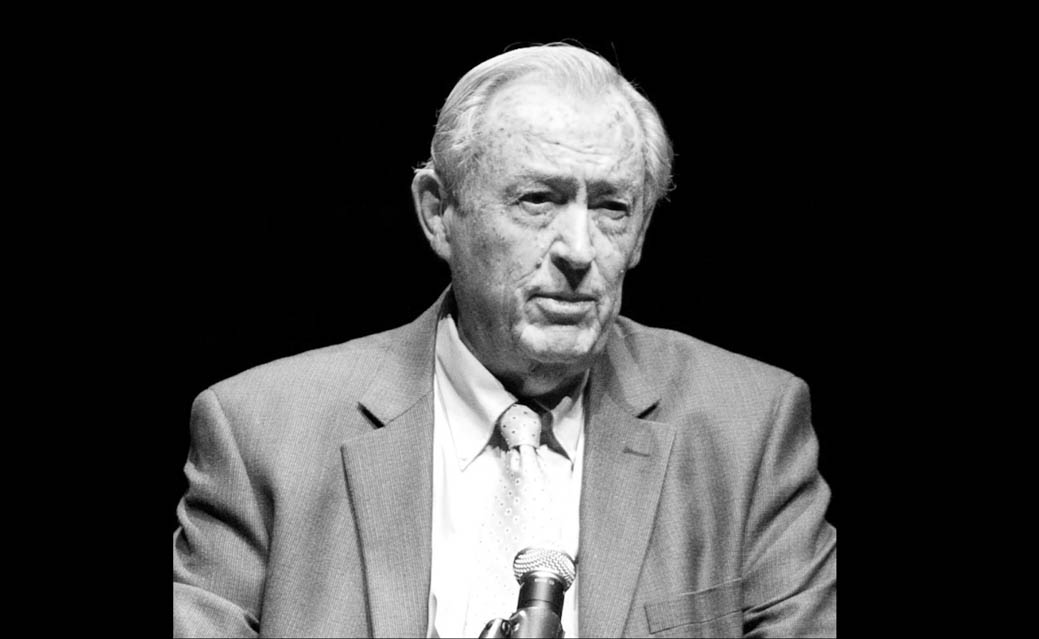

Paleoanthropologist and Wildlife Conservationist Richard Leakey Dies at Age 77

The Leakey Family was responsible for some of the biggest contributions in the study of human origins.

On January 2, famous Kenyan anthropologist, government official, and paleontologist Richard Leakey died at the age of 77. Leakey was the son of paleoanthropologists Louis and Mary Leakey. Together, they were responsible for the discoveries of many fossils that changed modern understanding of human evolution.

Dr. Lauren Schroeder is an assistant professor in the Anthropology department at the University of Toronto Mississauga (UTM). She teaches ANT302: Biological Anthropology: Primatology and Paleoanthropology, a course that discusses the diversity and evolution of humans among other topics. She defines the field of paleoanthropology as “the study of the anatomy, behaviour, and environmental context of our ancient human ancestors. Research in paleoanthropology can tell us about evolutionary relationships between species, the processes that led to our development as Homo sapiens, and how our lineage has changed over time.”

Richard, as a third generation Kenyan, spent most of his life in his home country. When Kenya became an independent state, he chose to keep his Kenyan citizenship. Richard grew up in East Africa, where his parents led excavations of the Great Rift Valley nicknamed the “cradle of humanity.” There, Louis, Mary, and their team made several important discoveries on human evolution. These include the discovery of the Proconsul, a common ancestor of humans and apes, as well as the “remains of the earliest man ever found” known as the “Zinj” skull—known today as Paranthropus boisei.

In 1976, Louis, Mary, and their team also discovered the Laetoli Footprints at Laetoli Site G in Tanzania. These became the oldest evidence of bipedalism—walking on two legs—in hominins, species that are human-like.

Originally, Richard was determined to avoid falling in his parents’ footsteps. He became a safari guide instead. However, while on tour near Lake Turkana, he discovered the site of Koobi Fora, a site that is known today as the “richest and most varied assemblage of early human remains found to date anywhere in the world.” Richard, along with a group of fossil hunters known as the “Hominid Gang,” discovered 400 human-like fossils, amounting to around 230 individuals. The most significant of these discoveries is the “Turkana Boy,” which was discovered in 1984, and is the most complete early hominin skeleton ever found. Richard moved away from paleoanthropology in the late 80s, but his wife and daughter, Meave and Louise Leakey, continued leading excavations in the Turkana region.

Richard’s discoveries, like those of his parents, further supported the growing theory that mankind began in Africa. While some scientists at the time disagreed with Louis Leakey’s interpretations of his findings, they could not argue with the significance of them. Louis’s discoveries would form the foundation for the subsequent research into the origins of human life.

Richard also put forward contentious theories of his own. His discoveries of hominin fossils led him to believe that there were multiple kinds of early humans, some of which went extinct, while others, such as Homo habilis (the earliest known humans), eventually became Home erectus, our direct ancestor.

“In general, much of the hominin fossil material from East Africa that has provided vital evidence for the evolution of our lineage was discovered during expeditions led by one of the Leakey family members,” says Dr. Schroeder.

She explains that all discoveries since have supported Louis Leakey’s theory of mankind originating in Africa, and it is now considered common knowledge in the scientific community. However, Dr. Schroeder notes that “it is important to point out that other early 20th century paleoanthropologists working in Africa, such as Raymond Dart who discovered the Taung Child in South Africa (Australopithecus africanus), were also advocating for Africa being the Cradle of Humankind.”

Richard Leakey’s achievements do not end with paleoanthropology. As a vocal conservationist, he was the director of the National Museums of Kenya from 1968 to 1989. He also became director of Kenya’s Wildlife Service (KWS), bringing it back from the brink of collapse. At the time, the poaching industry was slowly decimating the country’s elephant and rhinoceros populations, unbeknownst to most.

In that position, Richard became known for his ruthlessness, controversially ordering his park rangers to shoot illegal hunters, poachers, on sight. He also organized the burning of a cache of ivory to bring attention to the overhunting of elephants and rhinoceros. The “cremations,” one in 1989 and another in 2016, were carried out to send a message that ivory is worthless unless it is attached to an animal. In recent years, the KWS has come under scrutiny for the severity of their anti-poaching measures, with some even linked to unlawful deaths.

In his campaign to put an end to poaching and combat corruption in 1989, Richard made a lot of enemies and faced hardships. Known as being extremely combative, he entered Kenyan politics as the leader of the opposition party against the former president’s corrupt regime. He was publicly beaten in 1995 after joining the opposition, and was known to have bodyguards day and night during his tenure as director of KWS. Richard also dealt with numerous health issues, including a fractured skull as a child, kidney disease and subsequent kidney transplants, as well as having both legs amputated at the knee after surviving a plane crash in 1993.

After a career in politics, he turned his attention to climate change and telling the story of our evolution with his museum Ngaren: The Museum of Humankind, located in the Great Rift Valley, Kenya. This museum will hold Richard’s work, telling the story of more than two million years of human evolution and history, as well as a look to the future. In a statement, he said “Ngaren is not just another museum, but a call to action. As we peer back through the fossil record, through layer upon layer of long extinct species, many of which thrived far longer that the human species is ever likely to do, we are reminded of our mortality as a species.” Construction is set to begin this year.

The Ngaren museum will also display the work of his family, which has contributed so much to our understanding of humanity and its beginning. Dr. Schroeder touches on this in ANT203. “I discuss most of their major discoveries in my class. However, as they have discovered so much, I usually don’t have time to discuss them all!”

Dr. Schroeder notes that the field of paleoanthropology is continually changing as new discoveries are made. “This constantly changing understanding of our evolution in light of new fossil discoveries is what makes the field exciting, and the Leakey family has often been at the centre of this,” she concludes.

Staff Writer (Volume 48 & 49) — Hema is currently in her final year, finishing a double major in Linguistics and French Language Teaching and Learning. She previously served as a Staff Writer for Volume 48 of The Medium. Her favourite part of writing is the opportunity to research new topics, speak to new people, and make her voice heard, and she hopes that her articles can spark this interest in other students. In her spare time, you can find her in bed reading with a cup of coffee (and she's always looking for more book recommendations!).