Neglecting neurodevelopmental research in the Canadian Indigenous community

Oppression on Indigenous communities extends in disparities within psychological healthcare systems.

In recent years, there has been a push to promote more representative and distinct samples within research. A lack of diversity elicits serious ethical and equity consequences, preventing racially and ethnically minoritized (REM) populations from experiencing the benefits of tailored, high-quality healthcare.

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) is a neurodevelopmental disorder characterized by “persistent deficits in social communication and social interaction” that typically emerge within the first few years of life. ASD research has excluded equity-deserving groups, especially Indigenous communities, and continues to grossly lack diversity. Although ASD is equally prevalent across all races in North America, research of this disorder experiences inequalities in the diagnosis, treatment, intervention, and recruitment of non-Caucasian groups.

Several scholars have indicated that a key catalyst to this problem is referral bias due to researcher perception of children from REM groups. Health and human service providers as well as professionals can facilitate either conscious or unconscious cultural biases and prejudicial communication toward external groups.

Very little has been done to deepen the understanding of factors contributing to this underrepresentation. To address this gap—while it is limited—precursive research has been carried out to analyze strategies to promote better inclusion practices, more effective recruitment of diverse audiences, as well as address disparities in ASD “service access and care.”

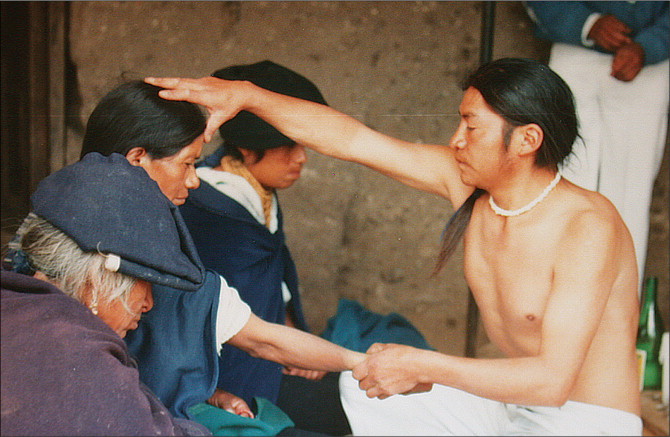

The unequal footing prevalent in Indigenous communities inhibits them from acquiring knowledge of economic, community, and healthcare resources. Fear of legal uncertainties, lower literacy rates, and linguistic boundaries have aided in the legal and healthcare distrust among their communities. Discrimination and prejudice have been key inhibitors in seeking access to services. It has been reported that Indigenous groups are more likely to trust community health workers from the same subculture as it decreases the stigma that occurs when seeking healthcare outside of their communities. For this reason, recent strategies have facilitated the recruiting and training of researchers from REM populations, as they share similar characteristics and experiences representative of the group they are serving.

Confounding what has been known as an “othering” disorder, healthcare in Indigenous communities has been difficult due to its low accessibility, as well as Canada’s tainted past of healthcare exploitation and medical negligence. Historically, research has been done on Indigenous communities rather than with them, causing distrust in the system. Indigenous women of Canada have been subjected by hospitals to forced sterilization. This lack of consent was justified by claiming an inability for isolated communities to raise children with a Eurocentric mindset. Sadly, not a thing of the past, these practices began decades ago and even crept into 2018, with the belief that no child could thrive on a reserve. Unfortunately, the severity of the issue is still unknown owing to a lack of comprehensive investigations and withheld public data.

Access to supportive services is limited, ASD awareness is low, and diagnosis is oftentimes delayed or worse, left misdiagnosed. Furthermore, this specialized support is oftentimes off the reserve, making the tailoring of assistance for Indigenous children with ASD not just challenging, but impossible. Eager to better integrate the lived experiences of autism within Indigenous communities into current research methods, there has been a dramatic shift to engaging community members within research directly. Retiring the old research model overseen by academic institutions which abided by strict ethics rules rather than providing a grassroots approach, recent research has seen more integration of people with lived experiences.

Integrity-based decolonization approaches rooted in community participation ensure any research done is with the community’s best interests in mind and it appropriately serves its target community. Equipped with a more humanistic lens, there is a hope that this new research paradigm will aid in influencing policy within and outside reserves and finally, ASD can be embraced rather than labeled.