Muslim representation in film—a conversation with Nesa Huda

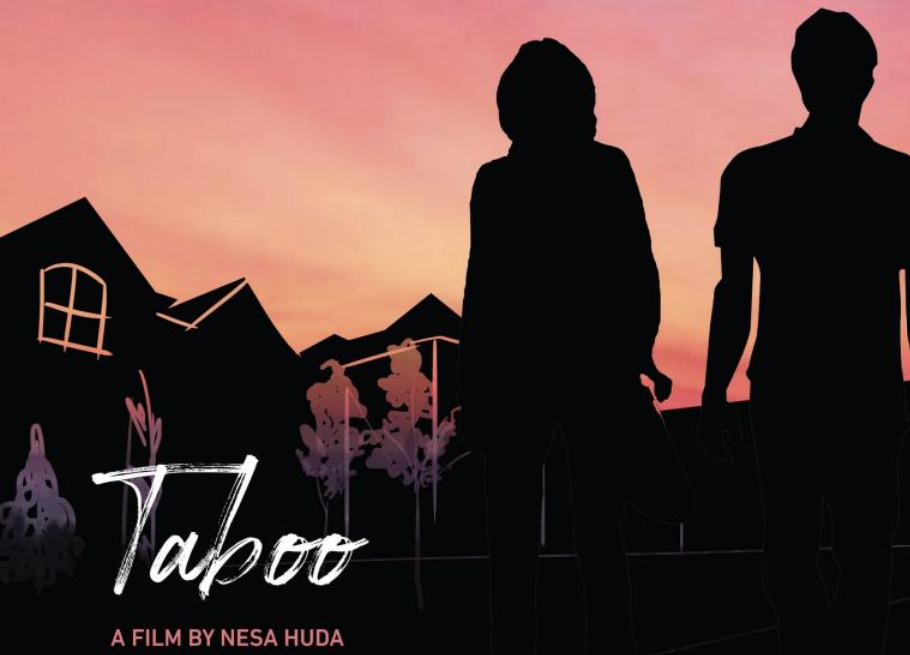

As the writer and director of her short film Taboo, Huda uses film to tell the stories that many fail to hear.

Trigger warning: This article mentions anxiety, depression, and suicide.

Nesa Huda is a filmmaker, writer, director, and University of Toronto Mississauga (UTM) alumna. On March 16, 2023, Innis Town Hall Theatre in Toronto premiered Taboo, a short film written and directed by Huda. In an interview with The Medium, Huda spoke about the development of the film, and how its story portrays struggles with mental health—specifically in Muslim communities.

Taboo came to Huda while she was still at UTM. The film’s concept was born from two life experiences that profoundly impacted Huda’s life. A close relative of Huda’s was hospitalized for a severe anxiety attack, while another friend of Huda’s suffered from depression, anxiety, and suicidal ideation. At the time, when her friend would share some of their feelings, Huda didn’t know how to help.

“I didn’t understand the language,” she shared. “I didn’t understand any sort of tactics [or] how I could just be there for that person, and so that’s kind of how the idea for the film came about. I [thought], how do we start those conversations with people? How do we support them?”

Taboo follows Naureen (Nawal Salim) as she attempts to make sense of her best friend Yousef’s (Abdul-Shakur Alawi) suicide attempt. Yousef, already in a precariously vulnerable position, watches his community shut him out. Although this exact situation hasn’t happened to Huda, Naureen and Yousef felt very real to her. She began writing the film’s script in October 2017, the year she graduated.

“I’ve been working on Taboo for so long, so to see that people were excited about it and that it touched [them] and that [they] found it relatable was just really nice,” Huda said.

Growing up in Windsor, Ontario, and attending Islamic school, Huda described her childhood as “sheltered.” An appreciation of film was instilled in her from a young age. Her family owned “a robust DVD and VHS collection,” she explained. She remembers watching movies with her family, and although she was not old enough to understand many of the films they watched, she said, “I understood that these films were bringing my family together onto a plane [where we could] all relate to each other, even if we weren’t good at expressing that.”

After her family moved to Mississauga, where Huda attended high school, her new environment became a nasty culture shock. “People like me were no longer the majority,” she explained, “and that took a huge toll on me and my self-image. I didn’t really understand where I fit into the social sphere anymore.” As she was frequently dismissed by her peers, Huda began to question her appearance and her identity as a Muslim Canadian.

As a child, Huda was a voracious reader. But when she was in her early teens, films and TV started to replace books. She would spend hours at the library, combing through films, taking them home, and watching two every night. But none of the movies she brought home had characters that looked like her. Even if they did, Huda said that they were represented as “terrorists.”

Based on her family’s experiences with discrimination and a lack of representation for her community in the media, Huda began to push her interest in film to a deeper level.

“I [thought], okay, if [the representation] is not there, then I’m just going to have to make it myself,” she explained.

After completing a Master of Fine Arts degree in Screenwriting from Boston University, Huda now lives in Los Angeles and works in the film industry. She described that she “tried everything”—from production design and videography to animation and production management—before realizing her true passion. “It always came back to this: I want to write the story, and I want to direct the team.”

I asked Huda how she hopes people will respond to Taboo. “First and foremost, it is about Muslims, and the fact that we are unable to properly address mental health in our spaces,” she started. “[While] I think it’s getting better, there is still work that needs to be done within our families and within our private spaces,” she said.

Additionally, Huda hopes for the film to be relatable for those who are Black, Indigenous, or a person of colour (BIPOC). She expressed that “many immigrant communities” tend to view mental health in similar ways.

Huda hopes to have BIPOC mental health professionals speak after future screenings of Taboo—to provide the audience with an open and constructive space to dissect BIPOC and personal issues. The short film’s Instagram, @taboothefilm, also shares resources relating to mental health and self-care. “This is not just a film, this is the start of a discussion,” Huda concluded.

Copy Editor (Volume 50); Associate Arts & Entertainment Editor (Volume 49) — Maja Ting is in her third year at UTM, completing a Specialist degree in Forensic Biology. In her spare time, she reads, visits the ROM repeatedly, waits for public transit, talks and reckons more than is good for her, and refers to herself in the third person.

while I appreciate this article and the perspective offered, with all due respect, I think that one might be overestimating the impact and influence of Muslim representation in film.

Furthermore, from my perspective, as an ethnic and religious minority of the middle East, for example, I think that the perspective here is unfair and hypocritical, because it does not address the lack of representation of non muslims in Muslim majority countries. The article complains about the stereotypes and stigma that Muslims face in Western countries, but it does not acknowledge the discrimination and persecution that non muslims face in many Muslim majority countries. The article also does not recognize the diversity and contributions of non muslim minorities in Muslim majority countries, and how they are often marginalized or excluded from film and media. I think also that representation in film is not only a matter of importance and necessity for Muslims in Western countries, but also for non muslims in Muslim majority countries. I think that this is a more fair and honest perspective, one that should have been addressed.