Max’s Big Ride returns for its seventh annual ride

Andrew Sedmihradsky cycles 600 kilometres to raise awareness and funds toward Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy research.

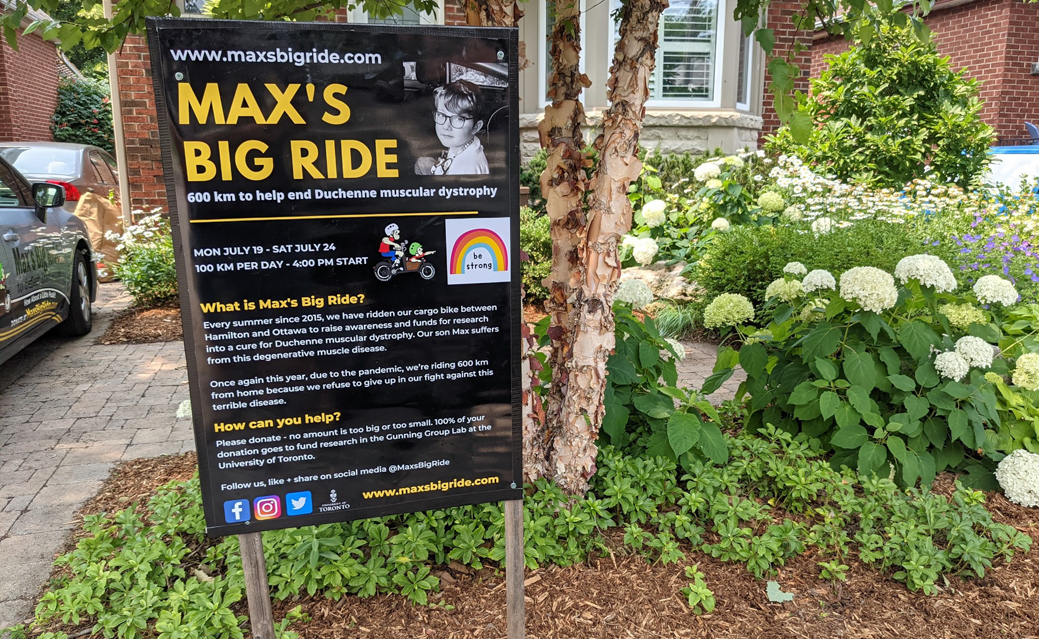

Andrew Sedmihradsky, the global mobility coordinator at the University of Toronto Mississauga’s (UTM) International Education Centre, walks to the front yard of his Hamilton home. He carries a large sign that reads “Max’s Big Ride” in yellow font with a black-and-white picture of his son, Max, sitting next to the title. Sedmihradsky hammers the sign next to his blossoming garden, officially announcing the seventh annual ride to raise awareness and funds towards a cure for Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy (DMD).

For the second year in a row, Max’s Big Ride happened at home due to the Covid-19 pandemic. Using Zwift, a virtual cycling app, Sedmihradsky hooked up his famous cargo bike to a trainer and began his 600-kilometre ride—covering 100 kilometres for six consecutive days.

When Max was diagnosed with Duchenne at the age of two, Sedmihradsky’s family was devastated. DMD is a rare genetic disease that weakens and damages the muscles in the body. This disease halts the production of dystrophin, a protein that strengthens and protects muscle fiber.

Duchenne develops in 1 in 3,500 boys around the world. Those who suffer from it experience frequent falls, fatigue, and problems with behaviour and learning. As time passes, DMD halts the lung and heart muscles; a fatal disease with no cure—yet.

“The way my wife and I dealt with this was different,” says Sedmihradsky. The day after Max’s diagnosis, he told himself, “I’m fighting this. I don’t know what I’m going to do, but it’s important that we don’t give up without a fight.”

Max’s Big Ride was Sedmihradsky’s response to Max’s diagnosis and has since built a community of supporters that have raised more than $230,000 in funds.

Family, friends, and neighbours gather around Sedmihradsky’s front yard. Some contribute money into a donation bucket, others bring food, beer, and signs to show their support—all while socially distancing.

“I felt like I was almost never alone,” adds Sedmihradsky. “There was always someone visiting the house.”

But Max’s Big Ride wasn’t always done from home.

Originally, Sedmihradsky pedaled 600 kilometres from Hamilton to Ottawa with Max up front, riding in a wooden box equipped with padded seats and a seatbelt. The final destination, symbolic to the Sedmihradsky family, was Parliament Hill, where important decisions on funding, drug approvals, and diseases are made.

The usual ride came with lots of planning: finding a safe biking route, booking hotels, booking a van for the return trip, and buying food and supplies.

This year, Sedmihradsky couldn’t risk the health and safety of his family, so he made the important decision to do Max’s Big Ride from home—a decision he doesn’t regret.

Though he misses interacting with the numerous communities that he normally passed by on the way to Ottawa, Sedmihradsky states that riding at home comes with many advantages that weren’t present in the usual ride.

“It’s certainly nice to be able to sleep in your own bed at night,” chuckles Sedmihradsky. But really, “the biggest [advantage] is the outpouring of love from the community. It’s really hard to walk away from that.”

On some days, riding from home gave Max the opportunity to pedal his own stationary bike along with his sister, Isla. Max rode for as long as he could, often lasting up to 20 minutes.

Even though he is losing mobility due to DMD, Max did his best to come out and cycle along with his father—and community members cheered him on. At one point, a group of supporters asked Max what his favourite food was. They learned it was pickles. “So, they went to a farmer’s market and bought him some pickles,” recalls Sedmihradsky with a smile on his face. “It was really cool.”

This year, Max’s Big Ride raised more than $30,000 in donations. Every penny goes straight to the Gunning Group Lab at the University of Toronto Mississauga. The lab, run by UTM chemistry professor Patrick Gunning, continues to deliver promising results against the fight for DMD.

“We had a PhD candidate from the Gunning Lab, who lives in the area, [visit] our house a couple of times,” adds Sedmihradsky. “It was neat to have her drop by and give us a little bit of an update [on the research] and also just to chat with her.”

Gunning’s Lab is currently working on refining their molecules so that they can move onto the next step: animal testing on mice. Like humans, mice can also develop DMD, though they have a much-accelerated lifespan—making them ideal candidates for testing.

“The feedback that comes back from the lab is encouraging and exciting,” states Sedmihradsky. “It’s exactly what we want to see.”

Max’s Big Ride has taken advantage of today’s digital connectivity in many ways, the most prominent being My Big Challenge, an initiative where individuals or groups set themselves a challenge to raise awareness and funds for DMD research. My Big Challenge isn’t necessarily tied to extreme physical challenges, such as riding 600 kilometres in six days. In the past, participants have hosted bake sales, raced up hills, walked two kilometres a day, paddle boarded, or even read books for the duration of Max’s Big Ride.

Yet, some participants have taken the challenge to the next level, for example with doing the Everesting challenge: a challenge where participants pick a hill and repeatedly climb it until they’ve hit a distance of 8,848 meters, the equivalent height of Mount Everest.

This year, an increasing amount of My Big Challenge participants displayed what the future holds for Max’s Big Ride. The higher the participation and engagement rates for My Big Challenge, the more funds Max’s Big Ride raises toward DMD research. For the past two years, all of this has happened without the need for a physical 600-kilometre ride to Parliament Hill.

“Riding from home is something that we’re seriously considering making a permanent thing, rather than going back on the road,” explains Sedmihradsky. “[Max’s Big Ride] has the potential to grow as a [worldwide] community event.”

This September, Sedmihradsky will attend the University of Toronto for a Master of Health Science in Translational Research. The program explores how concepts, such as scientific findings, can be translated into tangible innovations that benefit overall human health.

“In the beginning, I thought: who am I? There are all these scientists working on DMD. How am I possibly going to make an impact?” says Sedmihradsky. “[Max’s Big Ride] has shown me that a regular person without any scientific knowledge, with sheer determination, can make a difference.”

The future of Max’s Big Ride looks bright. Though it started as means to raise awareness and funds toward DMD research, the initiative is taking a new direction: “We’re starting to work on advocacy and ways to influence the direction of research,” expresses Sedmihradsky.

At the end of this year’s ride, Sedmihradsky put away the front yard sign and sat down with his family to watch the Olympics: “I had the right to sit on a chair and watch other people do stuff for a while,” he snickers.

Readers can visit www.maxsbigride.com to donate money for DMD research or sign up for their Big Challenge.