Halloween is a celebration of multiculturalism

Halloween spans beyond the horrific costumes and parties—it gives us a time to reflect on multiculturalism and traditions.

As a child, there were few days more exciting to me than Halloween. I looked forward to the 30 days of counting down to the celebration once October began. I watched decorations go up in my neighbourhood, bought and carved pumpkins, and figured out what I was going to dress up as (which was always some form of princess).

It was never a question for my parents whether my brother and I would celebrate Halloween with our peers. When my grandparents immigrated to Toronto in the late 60s, they participated in Halloween, even though the holiday was not celebrated in their home country of Trinidad until recently. My mother and her sister grew up with costumes and trick-or-treating, and when my father came from Trinidad to Canada in the 90s, he also knew that his kids would experience Halloween just like the other Canadian kids.

While I was initially surprised that Halloween wasn’t a very big celebration in Trinidad, upon reflection it made sense to me. Holidays that are tied to religion—like Christmas and Easter—tend to have a greater presence in the Caribbean. Instead of religious foundations, Halloween was marked by the Celts at the transition from summer to the colder seasons, usually around the end of harvest time. Trinidad is an island with a relatively constant climate—a holiday marking the change of seasons wouldn’t have come naturally. It makes sense that my grandparents and father weren’t exposed to Halloween outside of television.

Knowing that my father and grandparents had limited exposure to Halloween, I can look back and appreciate that my parents have always done their best to make sure that my brother and I never felt excluded from activities that our peers were participating in. My grandparents embraced holidays that they didn’t know of in Trinidad—like Halloween and Thanksgiving—and my parents took that even further. We were enrolled in programs like Girl Guides and fencing (which I loved) and encouraged to go on our school’s camping trips and ski trips. With a little cajoling, my parents allowed us to go to friends’ parties and even sleepovers. Though it may not have felt like it at the time, in retrospect, my parents were definitely more lenient than they could have been.

While they made sure that we experienced Canadian traditions, they also took care to see that our Trinidadian traditions weren’t ignored. We fasted for Diwali, went to prayers held by family members, and grew up eating Trinidadian food.

For the majority of my life, this “exposure” to both cultures has largely existed in the bubble of my own family, and I have the sense that this was a similar experience for other children of immigrants. “Traditional,” typically non-Canadian celebrations are carried out at home, and some families may or may not choose to engage in more mainstream celebrations. Recently, however, I’ve noticed that the way things are celebrated is changing, and it’s going both ways.

As a tutor, I hear stories from my elementary school students, and I have been pleasantly surprised to hear about how many learned about or participated in Diwali activities this past week. I’ve heard stories of teachers who typically don’t celebrate Diwali, Eid, or other holidays being cognizant of them to support their students. Just as kids are encouraged to decorate their classrooms with pumpkins and skeletons this month, they were also encouraged to come to school in their traditional attire and talk to their classmates about what and how they are celebrating.

This kind of openness and eagerness for multiculturalism is not something I experienced when I was in grade school. Not out of malevolence—there just wasn’t much awareness. As time goes on, and the peers of my generation re-enter school—this time as teachers—I’m extremely gratified to see how our experiences as multicultural Canadians are informing our lessons for younger generation.

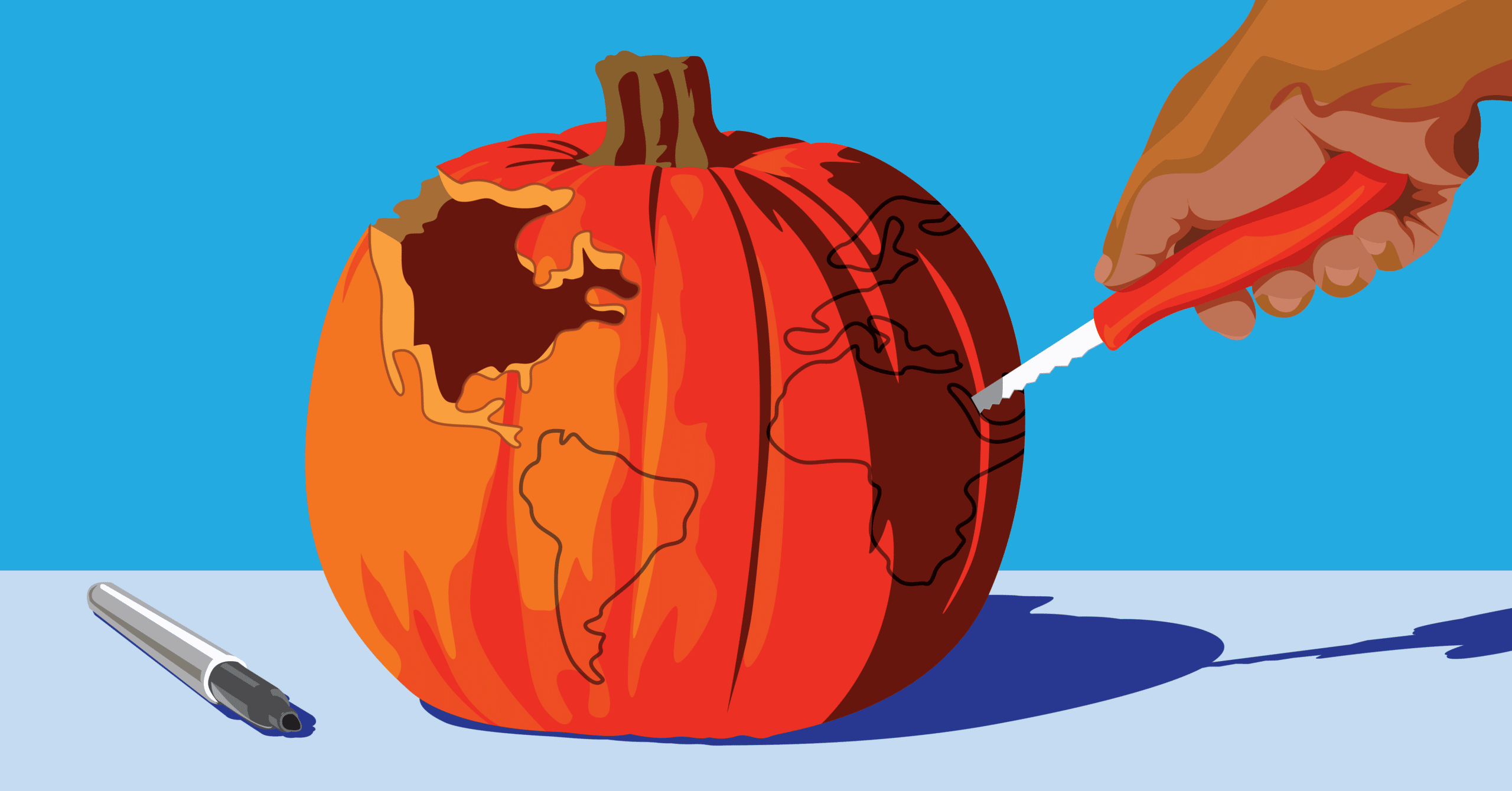

As for Halloween and Trinidad, I mentioned that it’s going both ways; in recent years, the holiday has taken root in the islands, mostly as a party event for clubs and fêtes. However, before Covid-19, more and more kids were starting to get out, dress up, and trick-or-treat. I hope the celebrations resume this year. One of the benefits of a globalized world is that we can take part in everything our world has to offer in a fun and respectful way, while also embracing the traditions that define us.