All history is written in pen

Ink bleeds through more than textbook pages.

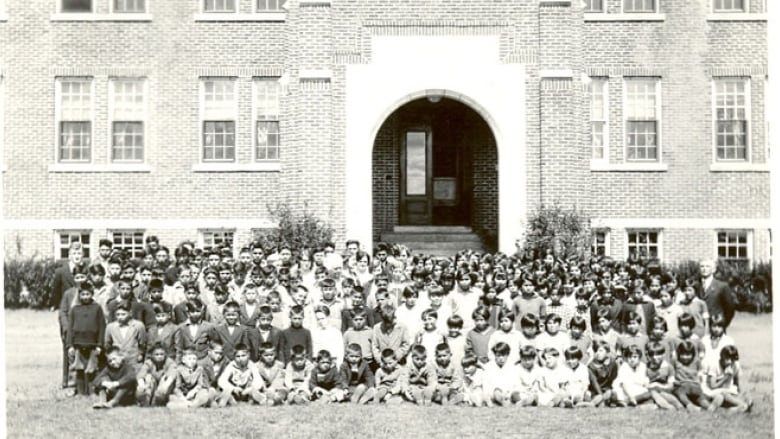

Only 26 years ago, in 1996, the last working Residential School closed its doors in Saskatchewan, Canada. The school system was advertised to give children a new outlook on the expanding state of our nation, teaching them a curriculum approved by the Church and Canadian government. There, they would learn English and religion—merging their cultures and existences with the colonizers who made their way to their land. Except, these schools did not aim to merge with Indigenous communities; they imposed their beliefs on young, defenseless children—leading to hundreds of violent deaths, and thousands of ruined lives.

Indigenous children attending these schools faced a complete erasure of identity. Stripped of their clothing, families, and languages, these students experienced unrelenting sexual torment, physical abuse, and psychological warfare. The government did not choose to instill “Canadian culture” into these children, but rather elected to diminish any existence of Indigenous language and traditions. It was a genocide with repercussions greatly impacting the community today.

When I was 10, I read a biography in order to qualify for a book competition. In the autobiography of her life, Shannen Koostachin of Attawapiskat has stuck with me for the last decade. She was a young Indigenous girl, who has since passed in a car crash, but has made such a beautiful impact on society. Within the biography, she speaks of the education system in Attawapiskat and her demand for an apology from Stephen Harper, the Prime Minister at the time. The grounds of the sole elementary school in the area were contaminated by a neglected toxic diesel leak—one the government refused to rectify. The horrible state of the reserve led to many people falling sick, and many committing suicide.

Dreaming of an education, students filled portables, hoping for a better future—one where they have equal opportunities to non-Indigenous students living in popular areas.

Shannen first introduced me to the horrors of Residential Schools, the lack of healthcare and water, and the suicide crisis amongst Indigenous youth. It was through her that I learned of the stolen children, the women who never made it home, and the inequity Indigenous Peoples face within healthcare. But most importantly, she opened my eyes, at a young age, to how Canadian politicians pretend to care, but truly do not.

Across Canada today, over 1800 unmarked graves have been found across Residential Schools—extending Residential School crimes beyond death. It is suspected that at least 1 in 50 children died, raising the anticipated number of total murders to 4100. To the children that survived to become adults, they endure the repercussions of these schools 26 years later.

These adults are shown to have higher rates of chronic infections and diseases and high rates of depression, but due to the lack of accessible healthcare, they endure a cycle of total silencing—unable to receive the help they need from those who make empty promises of reconciliation. And with limited medical resources comes limited mental health resources. About 25 per cent of Indigenous Peoples struggle with substance abuse—a significantly higher number than non-Indigenous people in Canada.

Indigenous reserves lack necessary resources for basic human needs. Approximately 85 per cent of Indigenous reserves are facing a water crisis. Researchers have found that water within these communities is infected with E. coli, cancerous chemicals, and uranium—further leading to the increased need of healthcare they do not have. At this point, this is blatant poisoning of an ethnic group. I dare call it an ongoing genocide.

After a century and a half since the first opening of a Residential School, we’d assume a non-existent disparity amongst the resources and equity accessible to Indigenous Peoples and non-Indigenous groups. Except, that is not the case. Suicide rates amongst Indigenous youths should not be six times higher than in other populations across Canada. Women should not be abducted while going on a walk. Indigenous men should not be incarcerated at a higher rate because of their ethnic identity. The truth is, the government is doing bullshit with reconciliation. Their efforts do not match what they need to do to make amends. And to be honest, their efforts to make amends will never be enough if they keep neglecting the water and healthcare crisis.

From reading Shannen’s story eleven years ago, I knew that it would be ignorant of me to pretend that my existence in Canada is not at the expense of thousands of lives. This country is built on stolen land, and there is no other way to put it. The responsibility for reconciliation is not solely dependent on the government, but also on us and what we choose to do with the stories we know. We must listen to the stories, talk about their experiences, and give Indigenous voices a platform to re-write the traditions and languages erased by hate. All history is written in pen. The government does not get to choose Indigenous history as written in graphite, willing to be erased at the flip of a pencil.