Between an Atom and a Star

I lost my grandfather on July 19, 2022. For the first time, “I’m sorry for your loss” took on a new meaning—and so did the essence of living. As I attended the funeral, the wake, the celebration of life—as I looked through his room and read his diaries, I desperately searched for the chapter unwritten.

I carry with me a piece of guilt that will forever be in the thickness of my skin. Deep regret that I took out the loneliness of feeling small in a big house on the only man that made every room feel full. An insufferable pain has showed me that I was never enough, and yet he loved me all the same.

The way I’ve told his story here has gone through many changes, and part of me has—and does—regret embedding myself within it, because when someone dies, you try your hardest not be selfish with your loss. But although one life is gone, and with it a story unfinished, hundreds of broken hearts are left behind.

There’s always more living to do, but we never choose who lives.

Among the stacks of papers he’d written, I found an eight-page essay titled, “How to overcome stage fright.” In blue pen, Dedia (my grandfather) explains how to turn fear into strength. He suggests doing so while smiling. This is my first attempt.

____

At the wake, we sit to his left, dressed in black as a hundred colleagues, friends, and students say their goodbyes. One by one, they bow their heads, whisper their parting words, and leave flowers at his feet.

I try to calm my trembling hands by digging my nails into my palms. The skin between my forefinger and thumb is marked with deep red crescents.

I wonder if anyone will ever have such perfect words to say about me.

I look at Mama, her expression veiled by her dark eyelashes; she stares right through me. I run my hand down her back and feel the urge to disappear, or to at least be too young for this to leave an impression on me. But I know it will.

It’s my turn to give a speech.

A hundred eyes stare at a stranger. I speak quickly, aching to sit back down, to hide behind the familiar armour of my mother and grandmother.

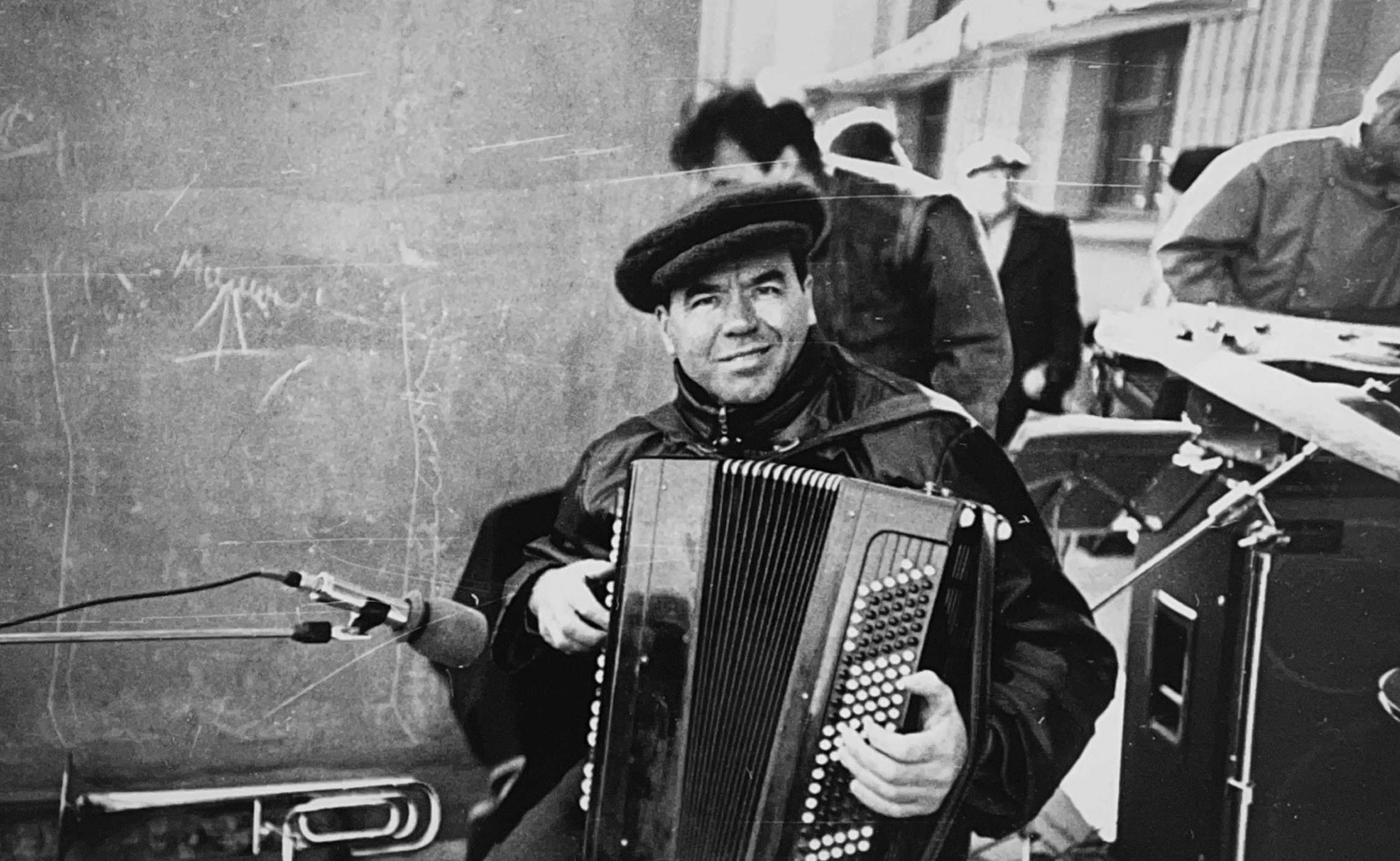

I remember being told the story of his performance at the “Carrefour Mondial de l’Accordéon” festival in Montmagny, Québec in September of 2000. He stepped onto the stage. The audience knew what instrument he played, but they didn’t know how to pronounce his name. He sat on the stool at centre-stage—a thousand eyes staring at a stranger—and began his set. He received a two-minute standing ovation after each song.

This will be his final standing ovation.

____

My grandfather, Viktor Koniaev, was born on January 17, 1939, in Orichi, a small settlement in the Kirov region of Russia. War was eavesdropping. Viktor lost his father, Sergey, to the war in 1941—an enemy bullet staining his white undershirt. Shortly after, his eight-month-old brother passed in great tragedy, leaving him an only child to his mother, Claudia. Claudia was uneducated, but she worked hard in pursuit of a better future for her son.

Kirov was the first train stop on the evacuation route from Moscow to Siberia. Many fled to the region during the war, while others travelled farther, enduring colder climates to avoid the deafening echoes of the endless bombing. There was little choice. There was little living.

One settler in Kirov was a famous accordionist. Under the grey sky, heavy clouds, and stagnant air, he filled the streets of suffering people with his energetic tunes. He performed traditional songs that reminded war victims of a time before living was a feat of chance. Nobody sang or danced along, but he kept playing.

This stranger changed Viktor’s life.

Dedia—the nickname I came up with for my grandfather when I was two years old—could have been walking from school or to the grocery store when he first heard the unique sound of the accordion. Its tone played over and over in his head, springing to life in infinite combinations. He wanted nothing else.

A few weeks later, Claudia found a stool in between Dedia’s small hands. He played with the wooden spindles, imitating the musician he had seen on the street. His eyes were closed, head tilted to the sky; this became his signature pose—the one I would observe at the dinner table as something heavenly filled the room.

Dedia graduated from his mimical instrument and self-made sounds when Claudia bought him a garmon for his eighth birthday (the cheaper, smaller alternative to the accordion). The weeks of potato-scrap dinners were forgotten when the instrument fit snugly between his hands. Soon, he outgrew it and advanced to the larger instrument.

Dedia spent every minute away from school practising endless scales and playing songs, but when he completed the eighth grade, his confidence slipped. He didn’t believe he could dedicate his life to an instrument. So, at the age of 15, Dedia travelled to Kirov, the capital of the region, to become an electrician. In the two years that followed, Dedia installed and repaired wires, mounted lighting systems, and struck the bass buttons of his accordion every day after work.

After the war, and 27 million lives lost, there was an explosion of dance and music across the country as the spirit of celebration spread. Solomon Sakhar, a Russian Jew who fled Nazi occupation, founded organizations for musicians, orchestras, and dancers in Kirov. Dedia’s second feat of good fortune came when he met Sakhar, who admired his talent. They played at balls and danced at local city squares, re-imagining a bright Russian future. This was the start of Dedia’s career as a musician: self-educated, ambitious, and playing against all odds.

In 1958, Dedia was invited to accompany the Russian traditional dance group, Dymka. The ensemble, founded in 1956 by Sakhar and Boris Kobrinsky, travelled to put on shows around Russia, as well as more than twenty-five countries across Central and Western Europe, Asia, and Africa. In 1980, Dedia performed as a soloist at the Olympic Games in Moscow. He continued touring with Dymka into the 1990s, and in 1992, his dedication to his art, his virtuosity, and his achievements were recognized by the Federal Ministry of Culture, who awarded him with the Honour Prize—the highest distinction a musician can receive in Russia. He was also equally devoted to education and started teaching at the Kirov Musical Institute in 1965. He continued instructing until the age of 80, raising generations of accordionists—each boasting about their nationally-renowned teacher.

In early 1963, Dedia was invited to a birthday party. He was a popular guest at any celebration, but that night, his electrical training proved to be of more use than his accordion. The light in the dining room went out, leaving the party in darkness and Dedia unable to see the keys on his instrument. So, he climbed on a small ladder, swiftly screwed in a new bulb, and brought a warm glow back into the room. He danced with all 10 women at the party, but at the end of the night, he walked only one to the tram. Buying two tickets, he made sure she got home safely. “I noticed he had a nice hat and jacket,” is what Lulu, my grandmother, remembers.

Since they had met at the birthday party, Dedia had been taking her out every Sunday to the restaurant at the train station—the best one in town. But that summer, when Lulu travelled from Kirov to Staraya Russa to visit her mother, she didn’t tell Dedia when she was coming back, she only mentioned that they’d see each other upon her return. A few weeks later, when she arrived back in Kirov, Dedia stood on the train platform in a crisp white shirt, holding a fresh bouquet of flowers. It was the fifth bouquet he’d bought that week.

They were married on December 24, 1963.

The following year, Sakhar encouraged Dedia to complete conservatory training for the accordion at the St. Petersburg Musical Institute. Dedia continued to perform, travelling 24 hours in one direction to complete examinations between shows. He graduated as an orchestral conductor and was quickly gaining popularity.

Dedia dedicated his entire life to his craft. His mind was always filled with hymns and his fingers covered with calluses. His lungs overflowed with music—not air. Dedia loved what he did; his passion could never be a chore. He loved his instrument and the impact it left on those who had the pleasure of hearing him.

In 1999, my mother escaped the crime and chaos of St. Petersburg by moving to Québec, Canada. She missed home—the culture, the food, her parents. She wrote to Dedia, asking him and Lulu to move to Canada—for the same “better life.” Dedia wrote in a letter to her: “My biggest concern is that I don’t know if I will be of much use in Canada as an accordionist.” He was 61 years old. He worked for another 19 years.

From her childhood, Mama remembers endless music. In the late hours of the night, or when she was doing her homework, Dedia would press the keys on either side of the instrument, without expanding and contracting its bellows—imagining the sound as he gave a silent performance.

Dedia would wake at 7 a.m. and cross the city to begin teaching at 8 a.m. He strapped his 16-kilogram accordion to his body like protective armour. After his working day, he would hurry home and quickly eat a dinner prepared by Mama’s grandmother, Babulia. At the kitchen table—eating alone as Mama, Lulu, and Babulia had dinner earlier—he would call Mama over, and whisper “на-ка,” urging his daughter to steal a few dumplings or a piece of buttered bread at his “here you go.”

Despite the endless hours of work, the time seldom spent with family, and the physical demands of his job, he was happy—eternally happy and satisfied. He was also praised, appreciated, and loved. Not only for his music, but also for his character.

____

My blonde hair peeks out from underneath my silky black headscarf. I shove my index finger through the lace and scratch behind my ear. In the car, on our way to the funeral service, I scrape the polish off my nail bed. By the time we arrive, my left ring finger has lost half its colour. “Stop that,” whispers Mama, lightly swatting my hands from the comfort of the other.

The priest asks me to place a cross in Dedia’s left hand and a small icon of Christ at his feet. I lift the white blanket concealing his hands. His fingers look stale, almost blistered. I carefully position the cross between his thumb and index finger. The priest and the choir begin singing, reciting a prayer unfamiliar to me. I sign the cross upon my chest, remembering to motion from right to left as the porters close the casket and screw nails into its wooden frame.

Late in the day, one of Dymka’s retired dancers gets up to give a toast. “Once I saw him on my way to rehearsal,” she starts in Russian. “He was in his 60s. He was standing in an almost-empty bus. I asked Viktor, ‘Why don’t you take a seat?’” She continues, “I noticed his accordion on the seat in front of him. He was standing above, eyes peering at the instrument. He replied to me, ‘No, Tatiana, this seat is for my accordion.’” And so, as he ran to and from work, for 61 years, he didn’t sit—happily standing and affording a moment of respite for his precious instrument.

_____

We return home in the afternoon. Mama and I share a few words of regret over our mutual sense of not having known much about him despite loving him deeply. “We didn’t protect him enough. We fed him leftovers. We thought that just because he was the man of the family, he would be okay. Look at us now, three women,” she says, walking out of the living room onto the balcony.

I peel the black dress off my skin—the sun has left impressions of its folds on my body. I walk into Dedia’s room. It’s warm.

Over the next few hours, and the following weeks, in an enclosure no larger than two-by-three metres, I am surrounded by 50 years of memories, and from them I learn more about Dedia than I have in the 21 years of my life. In his fortress of remembrances, I am guided through his most private and vulnerable thoughts, his most memorable triumphs, and his most precious stacks of musical notes. His presence in the room is eminent.

I start at the small shelf to the right of the door. A few sheets of music hang loose, brushing against the rusted hinges. Mama and I go through thousands of notes, scores, and annotated books. I show her passages from newspaper articles he’s copied into a crumpled notebook. Mama calls these faded, well-loved, and probably forgotten scrapbooks “his internet.”

“He told me a few months ago he saved you a stack of special songs he wanted you to learn on the piano,” says Mama. “You should try to find it.” I tirelessly search for those scores, wondering which of the loose sheets are meant for my unskilled fingers.

I get lost in his writing. As the light peers through the dusty window, I sit on his twin bed, cross-legged, my body sinking into his bumpy, uneven mattress. I immerse myself in his cursive writing—in some places it’s neat, in others it’s barely legible. Even Mama can’t make out what he’s written. He writes about how to teach music, how to cook borscht, how to give out scores at competitions; he writes about how to play the accordion—when to exhale, when to inhale—how to be a good musician and a good man. He writes about his marriage, his daughter, his aspirations, and requests to God.

_____

Before our departure home, we visit his grave one last time. Thousands of tombstones, some big, some small, some maintained, others overgrown with tall grass and weeds. His gravesite down the “Alley of Stars” places him close to the entrance. In our two weeks in Kirov, the hundreds of carnations and dozens of roses have dried out under the hot July sun. But, at his head are two fresh flowers and a hope that his legacy, both as a musician and a man, lives on.

I recently came across a passage: “The scale of man—spatially—is about midway between the atom and the star.” Dedia is the closest we will ever get to a star.

Виктор Сергеевич Коняев

Вечная память. Любим.

January 17, 1939 – July 19, 2022

Editor-in-Chief (Volume 48 & 49) | editor@themedium.ca — Liz is completing a double major in Chemistry and Art History. She previously served as Features Editor for Volume 47, and Editor-in-Chief for Volume 48. Liz is extremely excited to have spent her time as an undergrad at The Medium, and can’t wait to inspire others and be inspired in her final year at UTM. When she’s not studying, working, writing, or editing countless articles, you can find her singing Motown hits at her piano, going on long walks by the lake, or listening to music. You can connect with Liz on her website, Instagram, or LinkedIn.