Squid Game—a reflection of reality

Netflix’s most popular show dives into the darkest parts of humanity.

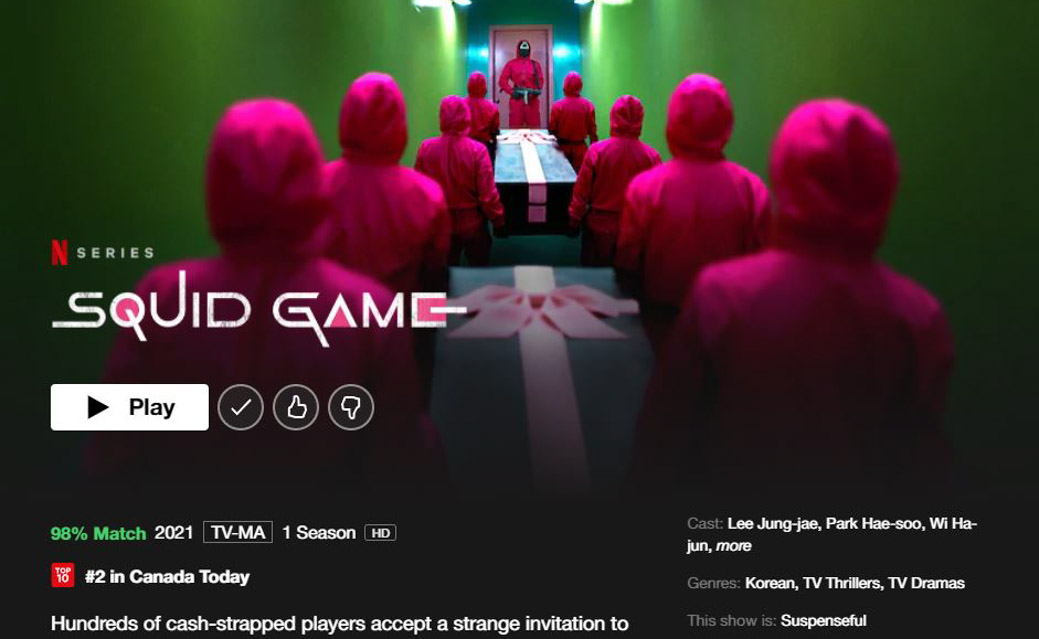

If you have had access to the internet in the last month, there is a good chance you heard about Squid Game—a South Korean Netflix series by director Hwang Dong-hyuk. No, it is not a cooking show, a marine documentary, or an animated show about an elite gamer who happens to be a squid. Released on September 17, 2021, Squid Game is a modern dystopia under the “death game” genre and is the most popular show Netflix has ever released.

All the characters, like Seong Gi-hun (Lee Jung-jae), are in debt and arrive at a mysterious place where they are invited to compete in six games to win a hefty cash reward. The series follows their stories of greed, capitalism, prejudice, and the inconsequentiality of life—exactly what we need when it feels like we are living in our own dystopia.

Hwang winds the stories of each episode together seamlessly; each injury, interaction, and consequence is never forgotten. The themes, and how Hwang expresses them, are immaculate; each aspect is rolled into one big, twisted commentary on human nature.

Each player has a reason for participating in the games, whether it be familial, medical, or personal responsibilities. The series introduces some of the characters’ origin stories, but even though their reasons propelled them to continue playing, those arcs do not return in significant ways. It is like the characters forget their incentives, making those stories irrelevant. Moral responsibility to family quickly turns into pure selfishness, which may be a commentary on human greed in itself, and ruins the sliver of empathy that each character embodies. It makes the characters feel disingenuous. Especially when faced with death, it is safe to assume that their original intentions would return, but they do not.

Hwang strains the moral compasses of his characters to display their capacities for selfishness and what they are willing to do to forgo death. What makes Squid Game interesting is how every player’s narcissism shows through their dialogue and interactions with other players, giving insight to their true personalities.

Squid Game does a great job of portraying the human condition. From birth to death, to the dichotomy between the hunger to win and alliances with competitors, every choice matters. There are multiple amazingly gruesome scenes where characters, who may not have been exposed to an extreme level of violence outside of the games, react differently to those who live dangerous lives. It is a small detail, but it gives the characters more depth.

One of the overarching themes is that the games provide equality between players. Everyone is given an equal chance to win and use whatever skills they have in this idealised structure. Meanwhile, it seems the game master sees themself as benevolent and altruistic, with complete disregard for the God-like role they have taken. The game master’s manipulation of the players’ indifference to death contributes to the insanity in each episode—reverse psychology.

There is something sinister in the art direction of Squid Game. The sets juxtapose the innocence of childhood—interactions in a colourful oversized playground and children’s games—with the corruption of adulthood. The visual aspects are simple. The characters are dressed in the same green athletic outfits and live in a warehouse. Every aspect of their individuality is stripped, which forces the most intrinsic aspects of themselves into the light and emphasizes their humanity. This combination adds to the eerie and horrifying aspect that makes Squid Game unique.

Many dystopian fictions often focus on the action—unnecessarily long fight scenes—and forget how consequences affect the characters, but Squid Game does the opposite. Any violence in the show is an accessory to the story and always has a consequence, whether it is a serious injury, impairment in other games, or even death.

Squid Game gives an emotional dark drama that destroys what people think they know about empathetic characters and “bad guys.” Viewers do not know who to hate, are forced to feel sorry for the bad guys, and are faced with the selfishness, naivety, and greed intertwined in society.

Staff Writer (Volume 48) — Sherene graduated with a double major in Communication, Culture, Information & Technology and Professional Writing. It wasn't until her third year at UTM that she realised she wanted to be a writer and thus began contributing to campus publications including The Medium. When she's not stressing over the anxieties of adult life with Buffy the Vampire Slayer playing in the background, she loves to write, draw, drink milk tea and buy more journals than she'll ever need.