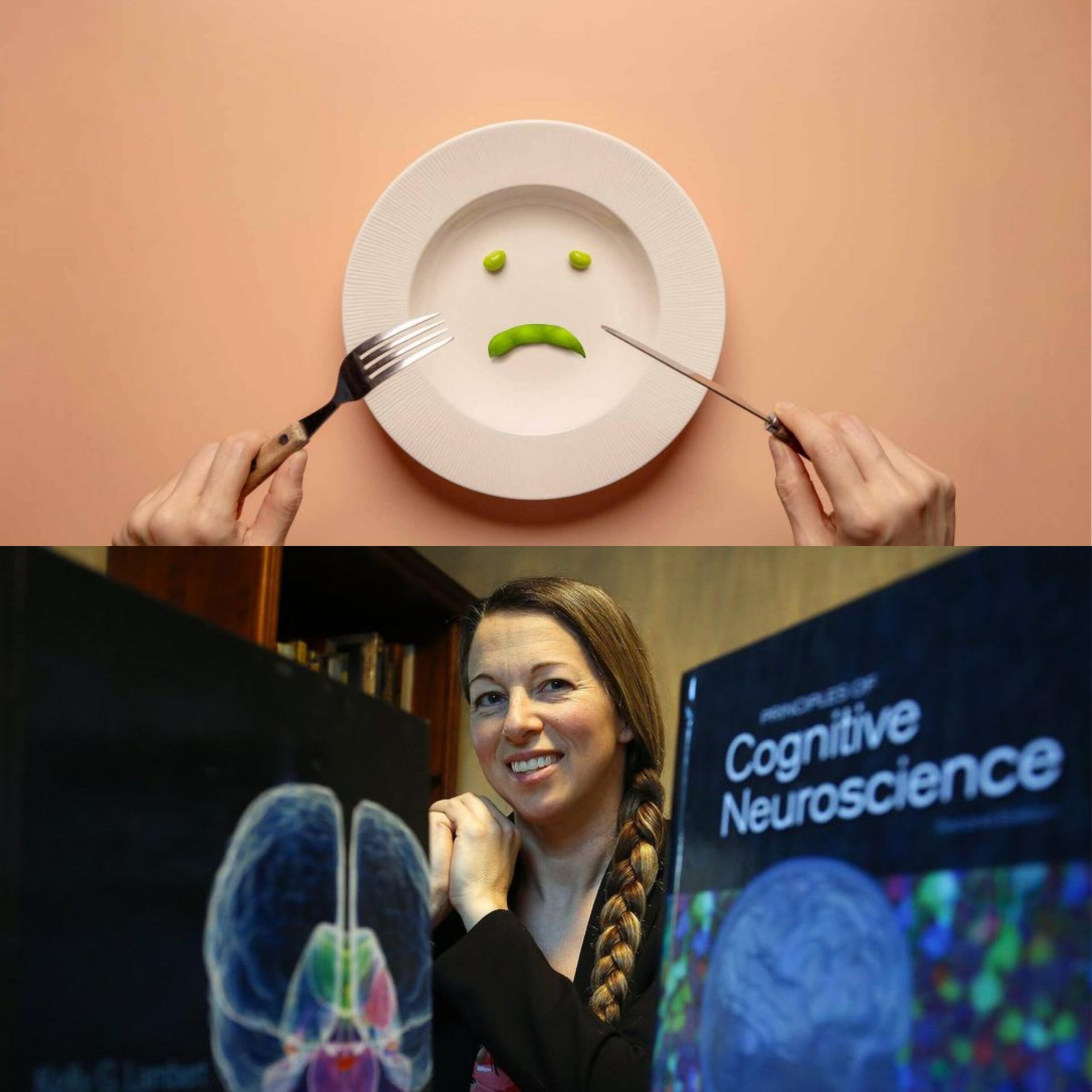

U of T lecturer Taryn Grieder on self-perception, eating disorders, and disassociation

Grieder discusses how we develop these disorders and how we can prevent them from getting worse.

Globally, one in eight individuals struggle with mental health illnesses. In Canada, this ratio is greater—one in four young adults experience mental health disorders. These include eating disorders and dissociative disorders. Together, they affect a large portion of the Canadian population. In her class on abnormal psychology (PSY346) at the University of Toronto Mississauga, Taryn Grieder, a lecturer and neuroscience researcher, discusses the importance of diagnosing these disorders and developing methods to treat them.

In an interview with The Medium, Grieder provides some examples of what an eating disorder can look like: “It includes disorders like anorexia, binging disorders, pica, and more.” She describes it as an unhealthy relationship with food, where your self-perception is distorted. Similarly, Grieder says, “dissociative disorders are abnormal self-perceptions.” This can happen if someone doesn’t know who they are or if they have multiple personalities.

Both of these disorders are psychological responses to stress. People who inhabit high-stress environments are most at risk for developing these disorders. For example, many people with low social economic status, or those with sick family members are at higher risk because their circumstances make them more prone to stress.

Adolescents and young adults are especially prone to eating disorders. Grieder explains that eating disorders often don’t fully develop until adolescence, when a person starts to learn more about the importance and effects of food. At this age, they also begin to perceive other people’s opinions of them and, unfortunately, start to grant them more importance than their own views.

Factors like social media that encourage a distorted self-perception can give rise to eating disorders. Social media applies pressure on people to look a certain way. Consequently, adolescents can become overly cautious of what they eat in an attempt to “look good.” Grieder mentions that “about 10 per cent of the population will end up experiencing [an eating] disorder,” with most being female.

Dissociative disorders, however, are much less common. Grieder states that “only about one to two per cent of the population identifies with this disorder.” It typically results from childhood experiences such as trauma or abuse. Grieder comments that the “symptoms don’t start showing until later in life, in adulthood, with their friends and the environment they live in.”

Grieder strongly encourages those who are concerned they may be showing symptoms to seek help through counselling and therapy. These services address the problem immediately, provide advice on what to do next, or in some cases, involve other professionals for more support.

Finding symptoms in yourself or others is reasonably simple with eating disorders. In Grieder’s view, “[these] symptoms are visible instantly after the person starts falling into it.” Symptoms may include feeling guilty about what you eat, obsessively checking calories, not allowing yourself to eat, or being in denial about any of these actions.

Though symptoms of dissociative disorders are much harder to see, Grieder notes that addressing the illness and seeking help as soon as possible is crucial. She advises looking for unusual behaviours such as not remembering notable events that happened, like forgetting a significant purchase or an important conversation. Although zoning out is a regular occurrence for most, zoning out for very lengthy periods can indicate an onset of the disorder.

As of 2020, over one million Canadians have been diagnosed with an eating disorder. An additional 1.5 per cent of the population currently battles with a dissociative disorder. Often, they can lead to further mental health issues. Alarmingly, eating disorders are the mental illness most responsible for suicide, the second main cause of death nationally. As such, Grieder stresses, “if you see someone or yourself showing symptoms, […] find help immediately.”