The brain science of being transgender

How science is an invaluable tool in combating misinformation and transphobia.

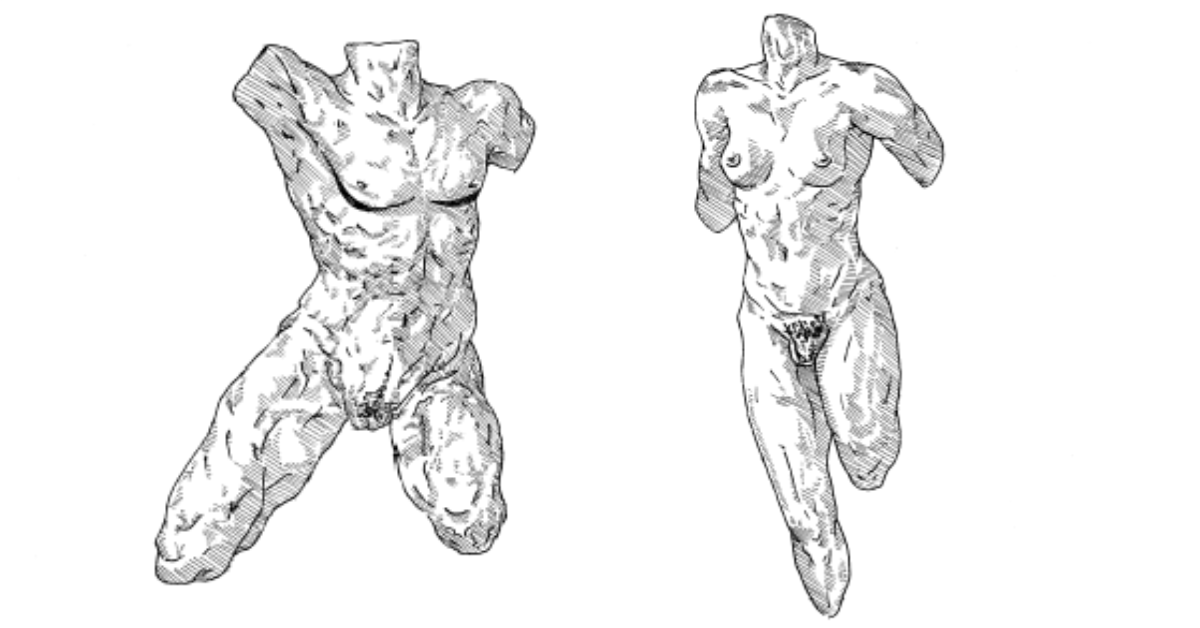

Throughout scientific history, both scientists and the public have been curious about the sexually dimorphic brain, otherwise known as the “gendered brain” in pop science. The brain is the most malleable organ in the body, perpetually influenced by genes, the dynamism of our environments, our internal experiences, and more. The interaction of these factors combines in exquisite and sometimes unexplainable ways to create the inexhaustible variety we see in our fellow human beings.

Only recently has science turned its attention towards unbiasedly and systematically uncovering the secrets of the gendered brain in relation to transgenderism. The incongruence caused by a mismatch between a person’s biological sex (defined by chromosomes, gonads, hormones, and genitalia) and their gender identity leaves traceable and measurable imprints on their brain. We now know that sexually dimorphic brain regions selectively respond to who an individual perceives themselves to be, rather than their assigned sex at birth.

We indeed live in a political world. All over the media, I hear debates and polemic rhetoric surrounding the “transgender issue;” of what rights these people ought to be afforded and the legitimacy of their experiences. In the end, I am left confused and disheartened by the hostility and misinformation perpetuated by both sides of the political spectrum. So, naturally, as a student of neuroscience, I turn to what science has to say.

The purpose of this article is not to provide a political opinion about transgenderism; it’s to represent the larger scientific conversation in a way that is digestible for all and why it’s important to listen to this conversation.

In his influential book: Behave, American neuroendocrinologist Robert Sapolsky writes that “it’s not the case that transgender individuals think they’re a different gender than they actually are. It’s more likely they got stuck with the bodies of a different sex from who they actually are.” With this remark, Sapolsky summarizes almost three decades of neuroscience research on brain and gender, and what it means to be transgender—no matter what stage of transitioning one is in.

Firstly, it’s important to state that many children and adolescents go through gender identity struggles. Yet, as they grow older, these struggles either resolve themselves or the child becomes a part of their LGBTQ2S+ community. In fact, only 23 per cent of childhood gender incongruence (discomfort caused by a mismatch between one’s gender and sex) leads to transgenderism. Surgically transitioning as a transgender person is also associated with improved psychological well-being.

According to one literature review, “Studies show that there is less than 1% of regrets, and a little more than 1% of suicides among operated subjects.” With some of my friends, I have personally been a witness to how their process of transitioning has benefited their lives. As mentioned before, the brain is uniquely sensitive and responsive to sex in a way the rest of the body isn’t, and when it comes to sexual development, the body and brain tend to develop asynchronously and at differing paces. By the time a boy hits puberty, they will most likely develop adult male genitals, acquire a deeper voice, and start growing body hair. However, due to atypical biological events in their past, their brain will resemble that of a female rather than a male. But what does this really mean?

A pioneering study from 1995 found that a specific brain region associated with sexual behavior was larger in males than females. Upon investigating this brain region size in male-to-female trans individuals, researchers found that this specific brain region was consistent with the transitioned sex (female) of the individual rather than their assigned sex at birth (male). Another follow-up study from 2000 tracked transsexuality as a function of the number of brain cells present in sexually expressive brain regions. Usually, males have twice as many brain cells in these brain areas responsible for sexual dimorphite attributes as compared to females.

After controlling for hormone statuses, sexual orientation(s), and social context(s), the study determined that male-to-female trans individuals did not have the cell count of their birth sex, but the sex they insisted they were. Likewise, female-to-male trans people had cell counts representing their gender orientation rather than their biological sex. These studies spearheaded the modern, and still progressive understanding of sex-gender mismatch: the idea that sex differences in the genitals take hold before sex differences in the brain, and that the lack of synchronization between these two processes might lay the foundation for transgenderism.

The unshakable conviction that one isn’t born in the right body is so far supported by science, but more research needs to be devoted to further replicating these results and exploring how gender identity is coordinated with brain function, hormones, genes, and more. What we do know is that being trans isn’t simply a feeling. It’s an intense and persistent psychological experience that originates from fully biological possibilities and results in distinct physical imprints on the brain as the organ matures.

Sometimes, transphobic rhetoric is bolstered by the claim that “switching genders is simply unnatural.” Even if something seems unlikely, not well-observed, or even downright impossible to us, the fact that it exists makes it, by definition, natural. The reality is that gender struggles are more common than people think, and it’s crucial that in an age of science, we as students commit ourselves to learning the facts of the situation and be open to new information with a compassionate mind.

Opinion Editor (Volume 51); Associate Opinion Editor (Volume 50) — Mashiyat (Mash) is a third-year student studying Neuroscience and Professional Writing and Communication (PWC). As this year’s Opinion Editor, Mash hopes to use her writing, editorial, and leadership skills in supporting student journalism in the essential role it plays in fostering intellectual freedom and artistic expression on campuses. When she’s not writing or slaving away at school, Mash uses her free time cooking cultural dishes, striking up conversations with strangers, and being anxious about her nebulous career plans. You can connect with Mash on her LinkedIn.