Surviving (and learning) in a subscription economy

Students are sick and tired of being forced to keep a separate piggy bank to pay for course materials and content they don’t even own!

“I cannot believe I have to pay 170 dollars just to be able to access the test questions for this course!” My roommate bemoaned the other day. This conversation brought back memories of being in first year and paying at least 100 dollars out of pocket for each course.

Once you finally get past the Hunger Games that is U of T course enrollment, there’s a giant wall in your way before you can actually start reaping the benefits of the exorbitant tuition you pay each year: buying textbooks.

Most first- and second-year courses at U of T require students to purchase hefty textbooks with hefty prices to succeed in the course, with professors often citing the fact that textbooks greatly supplement one’s learning. While this can be true, mandating textbooks to such a degree where a student risks losing participation marks without it or must budget harder because of the costs associated sounds fundamentally unfair to me.

Playing with piracy

First year courses are notorious for weeding out students to narrow the applicant pool and success rate. If success in a course hinges on buying extra materials, often masqueraded as “recommended preparation”, what about students who are forced to make a choice between all these extra textbooks and one month’s groceries? Most students cannot afford this, and it significantly hinders their academic success and enthusiasm, not to mention their mental health.

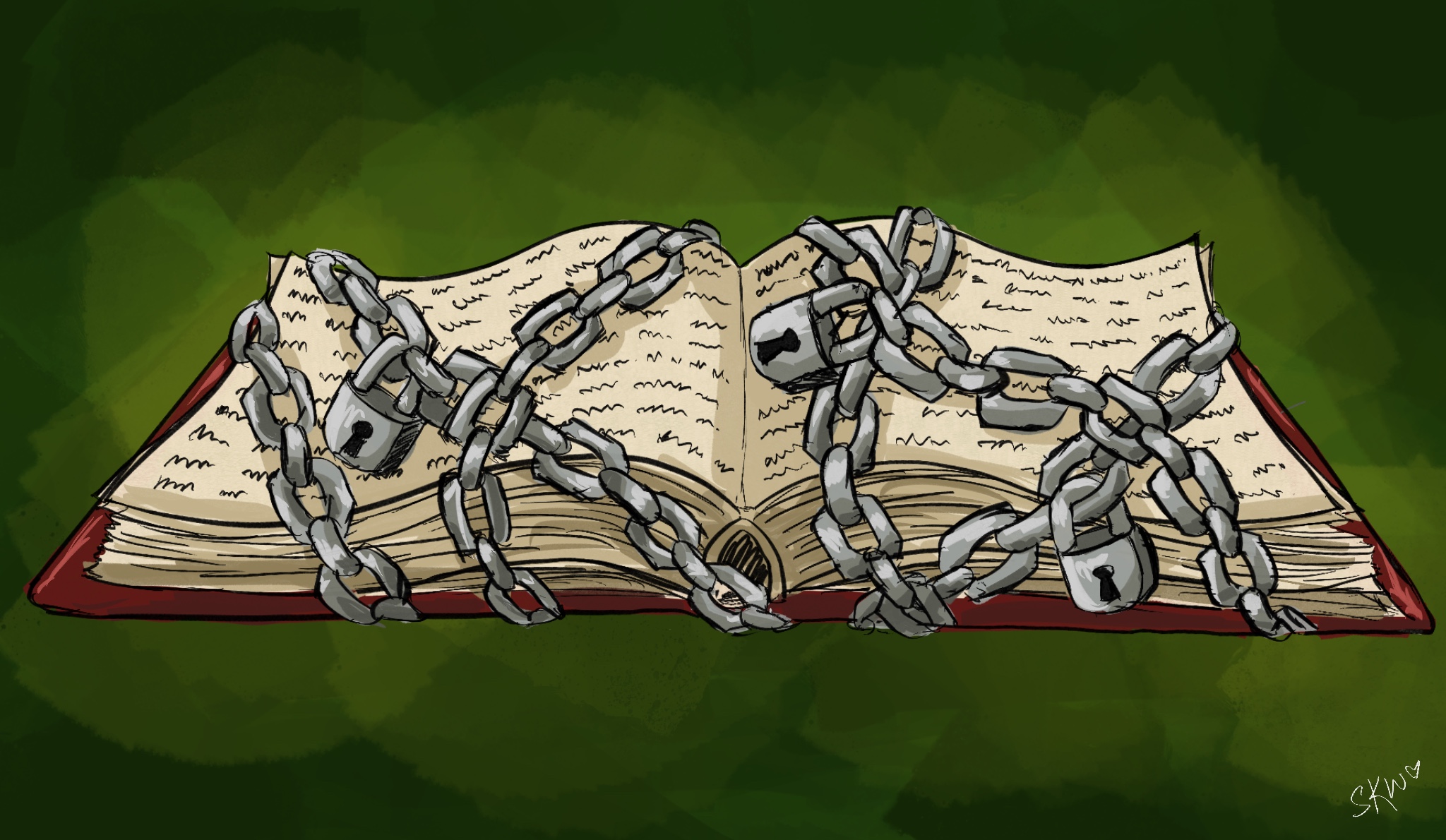

In lieu of buying textbooks from the official licensed companies, many students turn to pirating sites as alternatives to gain access to their required readings. Shadow Libraries refers to online databases of books and articles that are inaccessible for ordinary Internet users for a variety of reasons: the publications could be discontinued, out of print, not easily obtainable, or protected by paid firewalls.

The use of these pirated sites is problematic as it violates various copyright laws and can leave students liable to legal action, but it remains a popular practice among university students to cope with the inaccessibility of traditional textbooks.

Piracy is undeniably an ethical violation, as it constitutes a theft of intellectual property and utilizing an author’s work without appropriate compensation is condemnable. Piracy also puts the student who pirates at risk: from financial scams to personal data theft and security risks, piracy isn’t the best idea when it comes to digital safety.

But for students like me and countless others, it’s not so simple.

I am in no way endorsing that students forgo the violations and risks piracy represents just to save money, but the fact that many students resort to piracy indicates larger problems tied to questions of access, privilege, and worth in academia. Limiting access to credible and ground-breaking research by imposing paywalls highlights the gatekeeping and elitist nature of academia. But, this is the model that academia was founded and continues to thrive upon.

Pulling back the curtain on inaccessibility and true ownership

So, piracy is unethical, but so is the normalized exploitation of students, based on factors beyond our control, in the name of an education we paid for. Universities in under-developed and non-affluent countries also struggle with egregious paywalls (with no return policy) and structural limitations, which compromises their research and contributes to the larger problem of whose work is represented in the academic world.

So, why are academic journals and credible information so expensive and inaccessible, while misinformation is often left to proliferate free of charge? Taxpayers’ dollars and the government pay for research to be conducted, published, and distributed. What’s the point if such research will only end up in the hands of the few?

Having access to prestigious science journals like Nature means paying yearly or monthly subscription costs. How often have you wanted to read an article, only to realize you must pay $30 a week to access it?

In reality, a price tag seems attached to any content nowadays. From music to movies to documentaries, we are forced to pay our way into any “information” in this subscription-based economy, whether for entertainment or educational purposes. Having monthly or yearly subscriptions is not only indicative of how inaccessibility is built into our economic model, but also promotes and normalizes codependency with these “services,” and in the process, eradicates a true and genuine sense of ownership.

Who is really benefiting from this? The answer, my friends, is astonishingly unoriginal: corporations! Not only do they benefit monetarily, but they also take away the power of control, curation, and influence from the consumer, one subscription and paywall at a time.

In the throes of capitalism, nothing is sacred.

What professors should do: a student’s perspective

There has been a push in academia in the last few years towards open science, a movement with a goal to make scientific research, data, code, and publications easily and freely accessible to ordinary people, without the hassle of countless barriers. This is a very important step towards making science readily available to common people, which encourages and promotes transparency and equity, resulting in faster progress and leaving a greater impact.

Some U of T professors are also advocates of the open science movement, and this can be observed by the way they structure their courses. Many of my forensic science and psychology professors feature open access textbooks as the required reading for the class, removing the barrier of needing to pay to do well in the course. If there is a paid component, like practice questions, many professors provide the students with practice questions of their own in the lecture slides based on that paid material, so that no one needs to pay extra.

When it comes to streaming services and other subscription-based networks, the lure of such things is harder to escape. After all, there’s nothing better than coming home after a long day of lectures (and paywalled research papers) to the comfort of a Netflix show. While this is okay, as students, we need to remind ourselves that utilizing free resources at our local libraries or contacting researchers directly are ways to lighten the weight on our wallets when it comes to the prices we are often encouraged to pay for the sake of academic success.

Ultimately, the traction and popularity of open science has been steadily growing, and it wouldn’t be presumptuous to hope that in the next 5 years, most professors will break barriers and promote greater accessibility by no longer forcing students to pay extra for textbooks.