People’s Ignorance Won’t Allow for the Existence of Contradictions

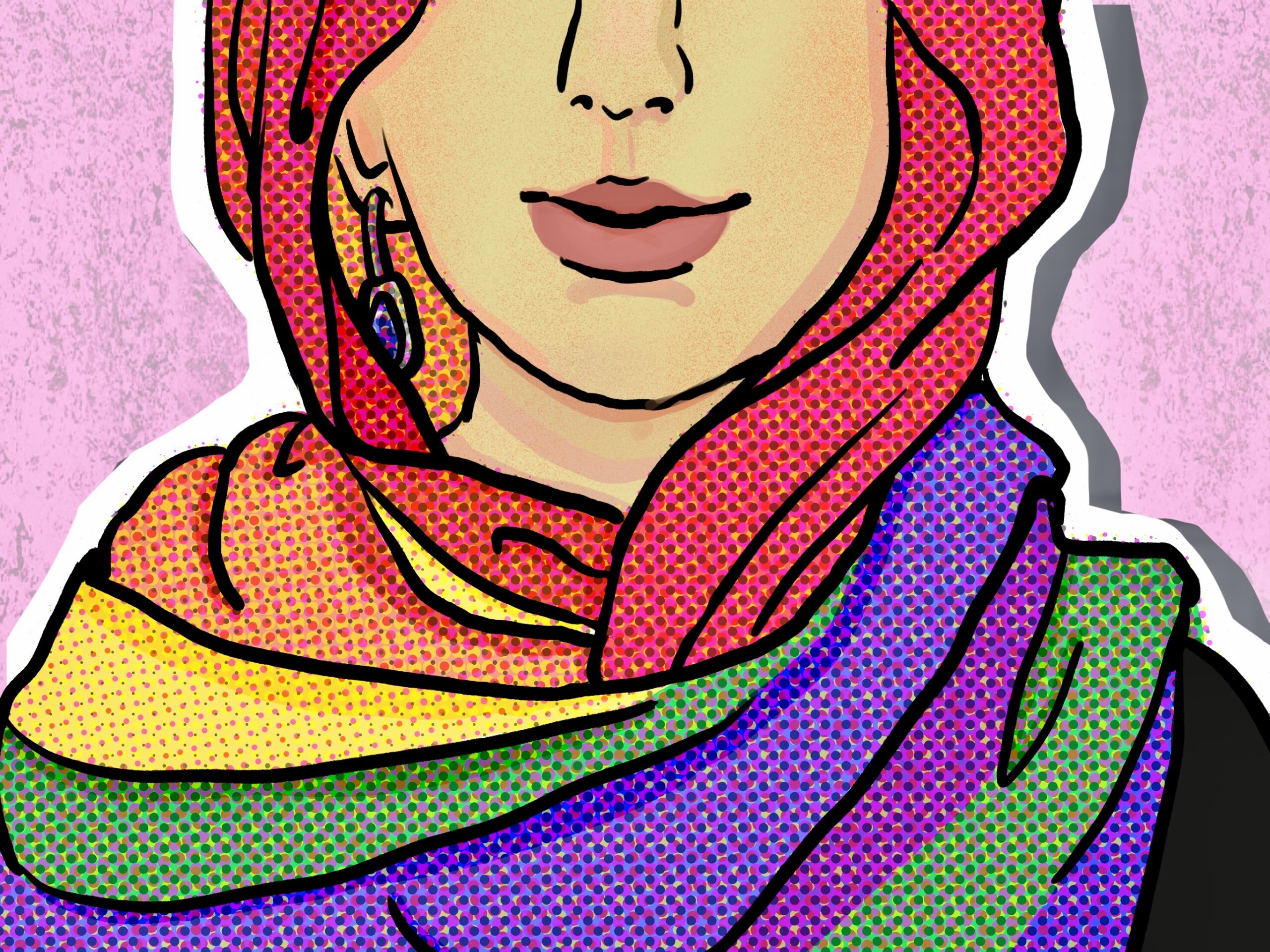

Being Queer and Muslim.

What is it like to be a queer Muslim? It’s difficult. It’s frustrating. It’s tragic. It’s liberating.

It’s none of your business.

But I have to make it your business because otherwise, your ignorance will end up drowning me. The cruel homophobia I see at home, at the mosque, online; the shocked faces people make when they realize that I am both queer and Muslim. It’s painful, and borne out of that pain are these words. I’m tired of the narratives other people create in their head about me. I am queer and a Muslim; what you consider as a contradiction exists in me — whether you like it or not.

The journey to this point of realization wasn’t easy. I grew up surrounded by homophobia: my math teacher in 6th grade used the word “gay” as an insulting joke; my 7th grade English teacher argued with me about how we shouldn’t treat queer students with “civility”; and my sister’s science teacher said that trans people aren’t valid.

It was easy to dismiss the stupidity of homophobic middle school boys, but to reject an ideology reinforced by so many of the authority figures in my life — who had degrees and lived experiences under their belt —was conflicting: surely there must have been credibility to their words? And so, I internalized the homophobia of my social and personal spaces, spewing hate in a hateful environment and building up the toxicity in my life until I was blinded to the harm I was causing.

Queer literature was my saving grace: the worlds of Percy Jackson and Six of Crows, the endless queer comics and webtoons I read incessantly — all helped to chip away at the hatred building up inside me.

It was the queer-friendly and inclusive experiences portrayed in these fictionalized tales that taught me that an alternative reality existed, even if imagined. Compared to the cruel world which taught me hate, fantasy and queer media kickstarted my questioning of the ideologies of the Muslim world around me, of my culture.

Why did the religion of peace — that said I should be kind, charitable, and just — for some reason excuse hatred towards queer people? Why was this acceptable? I questioned my own hypocrisy and my own ideologies. And while it was easy to tear down the homophobia I had built up in me, it wasn’t as easy to reconcile that with Islam.

In 10th grade, things took a more drastic turn: I realised I had my first queer crush. It felt like my own magical secret, like I had uncovered a secret part of myself that was all mine to cherish. I hid it away, accepting the fact that nothing would ever come of it because, after all, good Muslims don’t “act upon their sinful thoughts.” For the sake of religion, I was ready to give up on my queerness. Jealousy and grief built up in me — the sight of hands intertwined, of a rainbow flag fluttering in the wind — all twisted my heart.

Depression overtook me. I was completely alone, and completely helpless. I had no one to turn to, because all the “credible” Islamic scholars had the same answer to my question: that acting on queer thoughts is a sin, and that if I were to “give in,” I’d just end up miserable, condemned by God. I wondered if leaving religion was the only way I could settle the artificial contradiction between being queer and being a “good Muslim.” I was in agony over that choice — a choice which others shouldn’t have to go through. Wallowing in that contradiction is not something I’d wish upon anyone. It drove me into despair and I spiralled down online rabbit holes , all flooded with hateful comments that made me feel like something was wrong with my very existence.

Finding community is what saved me. A therapist at university — the first stranger I had ever come out to — told me it was okay to be a queer Muslim, that there were people like me that existed. That I could choose both. I found queer Muslim creators online who embraced themselves fully. Still, it was hard to let go of the chokehold orthodox Islam had on me: I second guessed everything I was seeing, the incessant fear of Hell preventing me from embracing myself.

Interestingly enough, it was hate that finally clarified my decision for me. A TikTok video I came across — of a Muslim revert excusing his own homophobia with the justification that Islam “gave queer people basic rights, but not all rights” — allowed me to accept an alternative way of being Muslim. I thought to myself: there is no way I could let myself be that hateful. I couldn’t practice an Islam that denied rights and humanity to people, especially when the Islam I knew was supposed to be egalitarian, the most progressive of all religions.

I don’t always feel secure in my current ideologies though. I still struggle with my paranoid religious self, constantly second-guessing my worthiness as a Muslim. But liberation theology written by Muslims (queer or not) that argue for a reinterpretation of the religion that focuses on social justice praxis reaffirms my beliefs and identities — one centered around humanity and fluidity, rather than degrading absolutes. Liberation theology speaks with so much kindness and compassion, using Islam to fight for liberation, to break down oppressive systems, and affirm the rights of all people.

I know that my experiences, or that my very existence as a queer Muslim woman, may be challenging to those of the more traditional Muslim faith. In my experiences, I’ve found such traditional faith spaces to spew hate, ignore the pain and suffering of queer people just to critique them, and focus on endless rules of Islam. If the God you believe in is that cruel, then I must ask you to question what you think mercy is.

Being a queer Muslim has allowed me to question every value I have ever believed in. It has elevated me to the best version of myself — a person that fights for justice for everyone, and not for some. Accepting my identity has been one of the hardest things I’ve had to do in my life. And I’d do it all over again if I had to (how contradictory)!