Painting Love: A Reflection on Love and Museums

Shortly before the first time I fell in love, we were standing in front of Alex Colville’s Soldier and Girl at Station. The couple was in embrace. He and I faced the painting, hand-in-hand, my thumb comfortably curled inside his palm. “He threw his bag to the side to catch her in his arms, he’s obviously arriving,” I argued, letting go of his tender grip and taking a step back for a new perspective. He argued that the soldier was leaving.

I went back to see the painting at the Art Gallery of Ontario many times during and after our relationship. It became familiar—my soldier came and left too. He was in the marines, and I was delusional. I quickly learned that love is flawed because we, as human beings, are flawed. Some flaws I’m actively working on, others I’ve accepted. For example, I enjoy taking the last piece of food on a communal appetizer plate, and I fall in love too easily. Love can be a smile in the morning, an “I love you” at the end of each phone call, or a shared cup of coffee—but love is also accepting your partner’s flaws just as much as yours. I was under the impression that love was perfect. I was wrong.

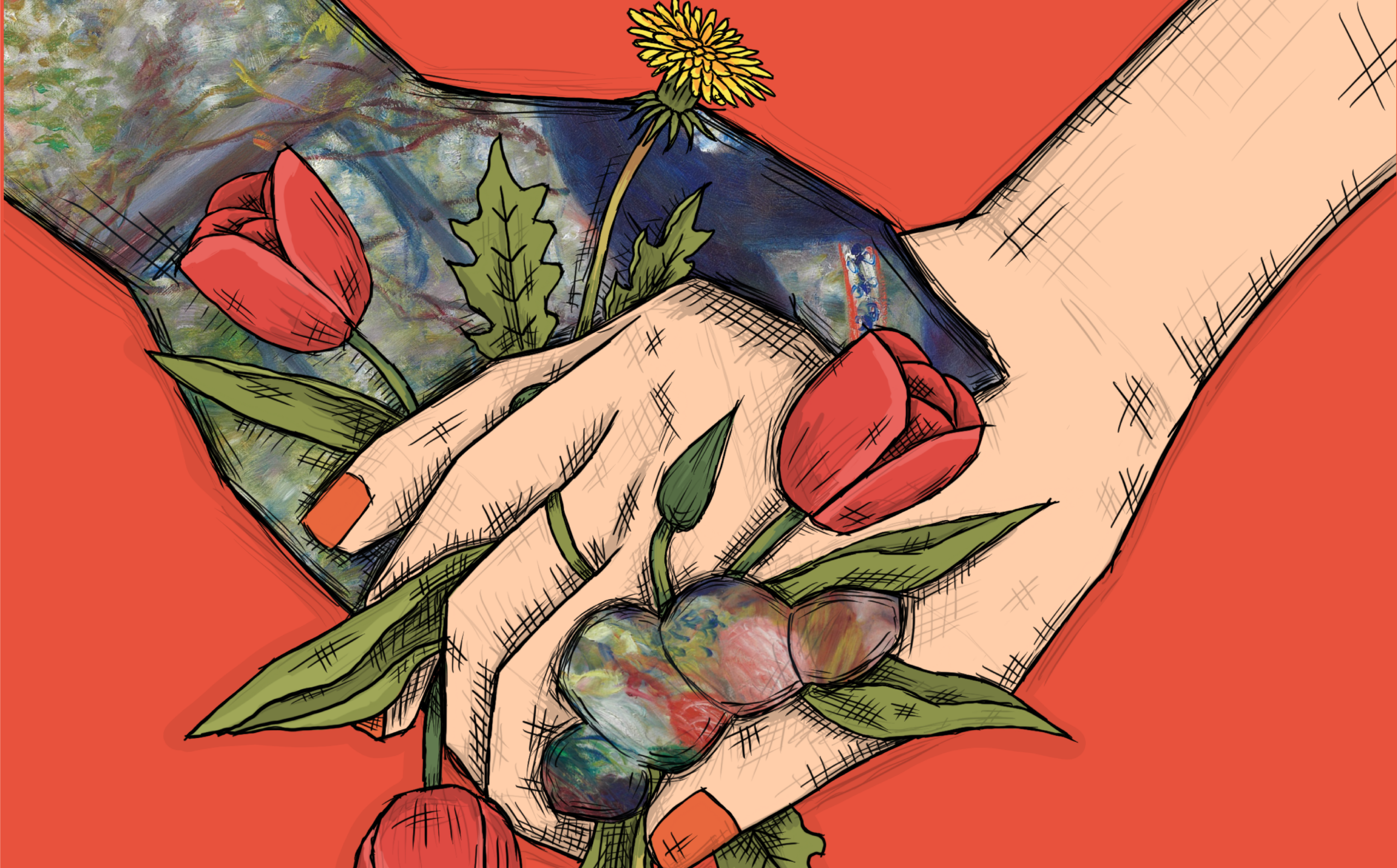

Religion, ambition, distance, and timing—so far, those seem to have been the reasons I haven’t found an eternal love. Heartbreak forced me to realize that we exist not as individuals, but as threads in an interconnected web of relationships—some nourishing, others deleterious and disheartening. Every relationship has its own purpose, sometimes evident in the moment, sometimes long after you’ve removed their contact from your phone and vowed to never speak to them again. Relationships—romantic or otherwise—rely on the emotional capacity of those involved. Love is not a 9-to-5. It’s a 9-to-5 followed by a 5-to-9. When I am single, I prioritize being emotionally available to myself; that is how I heal. When in relationships, I ask myself four questions: Are you willing to be vulnerable? Are you able to be a better person tomorrow than you are today? Can you listen when you would rather speak? Will you water the flowers even if they are weeds?

Before all else, I fell in love with art in 2014 while in St. Petersburg. My mother, an artist, brought me to a painting lesson off the Avtovo metro station. This was the first day that I noticed that art had always been all around me. Coming onto the platform from the train, I faced a crystal palace. We walked around the pavilion; the ceiling of the underground station was supported by 46 columns—30 lined with marble, 16 lined with molten glass. My mother told me the station was built and decorated to commemorate the end of the German siege of Leningrad during the Second World War. It was the first station of the second operational metro system of the country. A mosaic panel titled Victory adorned the far wall. A woman and a child.

The painting instructor, Igor, asked my 13-year-old self what my favourite painting was. He told me that I would paint it. This was an easy task for the last-minute addition of a teenager who was too old to be babysat but too young to explore the city on her own. I looked over at my mother, her eyes were fixed on the unlimited supply of oil paints. In the small art studio on the third floor of a Soviet-style apartment building, the unfamiliar Russian women were busy unpacking the chocolate candies, home-made pastries, and tea they’d brought to share with others. They made sure I was fed.

The only painting I could remember was from a postcard I’d seen at a gift shop a few days before. The back read “Pierre-Auguste Renoir.” French, like my father, I thought. Igor passed me his tablet and I searched the artist’s name. It was the first image that appeared in the results—Two Sisters (On the Terrace).

“Ah, Renoir, great choice,” Igor chirped. For the rest of the day, he spoke the artist’s name like one does to a baby, over-enunciating the vowels in a higher pitched, diminutive voice and smiling with his front teeth. “Renoir-chick,” he called him. He treated me with care, as if his own child was finally discovering the magnificence of the passion he loved deeply. He was delicate, both with the master’s piece and with my poor rendition. The picture was patient with him, and he was patient with it. I didn’t know you could love and respect art. Nor did I know that love was an art either; one that could also be learned, taught, and experienced with time. I would soon know this too.

I had never liked art museums before. In each new city we visited, my mother would bring me to these large, bright buildings with confusing floor plans. I always carried the map. When I was ten years old, she dragged me to the basement of the Hermitage. As we scurried past crowds of tourists with cameras bearing elongated lenses, she kept looking back at me, my hand in hers, saying “I’m going to show you Rembrandt, just you wait.” I stood next to her as she contemplated The Return of the Prodigal Son. I tugged at her pant leg, wanting to leave. She tried to explain the painting before us. The son kneeled at his father’s feet in repentance, pleading for forgiveness.

In my formative years, my mother endeavored to edify me with art; I, rather, was interested in eating gelato and building sandcastles. After my lesson with Igor, art became a material and medium with which to think, affording new octaves, new registers. The paintings and sculptures that drew my eye weren’t the ones that made it onto postcards—although those showed me beauty in all its forms; rather, I became captivated by art’s power to repair and resist.

Understanding art relies on an ability to be open and enter and engage in conversation. I asked Georgiana Uhlyarik, curator of Canadian art at the Art Gallery of Ontario, what role museums play in making art active in society. She answered, “Art is part of everybody’s daily life—whether they know it or recognize it or not.” The soft patterns of paws in fresh snow, the geometry of street signs, the varied textures of asphalt, and the lattes at your favourite coffee shop. Toronto’s Victorian homes, billboards, engines, and people coming together. The human body, bread, love, sex, and tears.

Uhlyarik recalled art movements at the turn of the twentieth century that worked to break down the hierarchies between textile work, furniture, painting, fashion, and ceramics, rather defining visual expression and art as a “communal and fundamental way of communicating that is preverbal.” Museums are still trying to disrupt these outdated orders by acknowledging that the rest of the world does not exist in hierarchies as we traditionally understand them—nor is society framed only in a white, Eurocentric moulding, she shared. “The future is, at least, the aspiration is, to create very welcoming, very active, very socially engaged spaces, but also to continue to be a space of communion.”

In The Future of Museums, Gerald Bast, rector of the University of Applied Arts Vienna, outlined that futurists argue that museums are cemeteries to which we take a pilgrimage once a year at most. They also argue that the fate of museum objects is akin to that of wild animals transported to the zoo. Bast explained this by comparing the reactions of an elderly couple with that of a child when presented with Baroque art. The Massacre of the Innocents by Peter Paul Rubens at the Art Gallery of Ontario depicts the execution of all male children in the vicinity of Bethlehem under the order of Herod the Great. Bast posed that with sight of such a painting, the elderly couple will admire the aesthetic beauty of the bare bodies and the technical perfection of the artist’s work, while the child, frightened, will want to leave the gallery upon spotting tied, bloodied, gagged, green-faced babies scattered across the canvas. Ruben’s intent was neither of those outcomes—the painting was completed as a reflection on the massacres taking place in Antwerp, Belgium during the Dutch Revolt. It was meant to elicit dread, acting as a weapon of counter-reformation.

In the text, Bast asked: “Why are the visitors in a museum generally left alone with the superficial aesthetic effect of an artwork? Why is art in the museum so rarely experienced as an analysis of life reality and so rarely seen as a contribution to the development of social ideas?” Museums are moving to reframe our experiences to address these questions.

“What is great about a museum, in addition to getting to see the art, is that it’s a very contemplative space.” As a philosopher, Diana Raffman, a professor at the University of Toronto, deems the museum to be a natural space that simulates an experience akin to doing philosophy. The sensory, perceptual modality of art—one that doesn’t exist in literature, for example—places us in dialogue with the artist. In my opinion, what art, especially good art, asks of us, is a response. It draws us in, connecting us to its fibres, its material, its composition, and its subject. It asks us to inquire about what we see—to ask questions and to seek answers. Of course, acknowledging how well one paints, the history of a piece, and its provenance can allow us to determine with its value, but for me, the value lies in the response. Does the piece move me? How does it move me? Why does it move me? Raffman explained to me that the purpose of an artistic image is “not simply to prompt action, or to communicate a message, or to be a beautiful object, or to be aesthetically apprehensible;” rather, art pushes us into this “other” space where instead of acting, we contemplate.

The importance of humans and art across generations has been mutually inclusive—one does not exist, nor can it be valued, without the other. We have left our marks on caves, placed script on paper, and laid brushstrokes on canvas to show the life we have borne. Art is a mirror in which we have revealed our turmoil and our grief in painted faces and sculpted bodies—sometimes appearing tenderly, sometimes grotesquely. Art captures what is fleeting, making us feel alive despite being stains and fading letters in the library of history. Art is beauty, and beauty is the antidote to our suffering.

The last time I visited my father in Montreal, we attended the Museum of Fine Arts. We walked through the exhibits slowly. I savoured the rare moments I shared with him, and the rare moments I shared with art. The museum didn’t feel like a cemetery, more like an eternal field of blooming tulips in the spring. I returned to it because it made me feel alive, injecting meaning and light into my veins. With each visit, even standing at the feet of the same works of art, I found new understanding. What was unclear—love, loss, sadness—became clear. The museum became my playground and my teacher.

The star exhibit at the Museum of Fine Arts was Nicolas Party’s—a contemporary Swiss visual artist—“L’heure Mauve (Mauve twilight).” The installation presented the indivisible unity of humans and nature in a colourful meditation. Party’s watercolours, pastels, and sculptures were set against works from the museum’s collection. The exhibit’s title referenced Ozias Leduc’s oil painting of oak branches fallen in the snow. In the winter scene, a purple glow reflects off the white landscape, set in the transitory moment between day and evening. It reminded me of the leap from action to acceptance—when the body and mind welcome the result. When the self acknowledges that what is meant to be isn’t always what is wanted. When I finally let go of the hope that what once was will come back.

My father was once a director, strengthening his love for the arts in visits to art museums. He and I shared a few breaths in front of Leduc’s L’heure Mauve. The artist’s name felt familiar, I told him. He reminded me of his documentary on Leduc—one of Quebec’s first Symbolist painters of portraits, landscapes, still lifes, and decorator of churches—he’d shown me a few months prior. I knew very little of what my father did, but then I knew a little more. In her work Collecting Piece II, Japanese multimedia artist Yoko Ono wrote, “Break a contemporary museum into pieces with the means you have chosen. Collect the pieces and put it together with glue.” That day at the museum, I did just that—I broke the exhibit down and glued it with the slivers of what I knew about my father. The picture was now different.

To love my father meant to engage with him. To give into his flaws, his imperfections, his demands, and to remember that he is human. To answer his emails and to show up at his door. In his book The Art of Loving, German psychologist Erich Fromm wrote, “Love is an activity, not a passive affect; it is a ‘standing in,’ not a ‘falling for.’ In the most general way, the active character of love can be described by stating that love is primarily giving, not receiving.” We often worry about how to be loved, or how to be lovable, rather than choosing to learn how to love. Love is not easy—it does not come without fail or effort. It can feel effortless—that is good—but it requires effort. Ultimately, love is a choice. It’s easy to love when the sun is shining, but real love involves bringing an umbrella when it rains.

There are very few lived experiences that start with tremendous hope and prospect, yet fail so regularly, as love. Overcoming the failure of love involves realizing that love is an art that can be learned and nurtured with time and experience. Van Gogh once said, “I feel that there is nothing more truly artistic than to love people.” That may be why most impactful artworks are about love, in one way or another. It is also why the recipe for loving one person will not be the same as for loving another, or for loving that same person tomorrow. Van Gogh’s oil paints were predictable—he knew how the colours would behave when he used certain brushes or painted on certain canvases. But people are imperfect and unpredictable, so loving them is a far greater endeavour than painting.

I’ve learned that understanding art and love in the modern day requires letting go of the conventions of both. Boundaries, limits, and expectations cannot be set; love and art are boundless. They exist beyond our capabilities and even our understanding of them. In many ways, love will always be passion, strength, care, and beauty. Art will continue to be a love letter through colours, pictures, and lines. The familiar memory of sending an image across the ocean with a “This made me think of you” was a love letter, revealed in the way the brush strokes touched the canvas, immortalizing that which I could not explain with words.

In his 1991 memoir-in-essays, Close to the Knives, American artist and activist David Wojnarowicz details his story in fragmented acts and sights. The final essay, “The Suicide of a Guy Who Once Built an Elaborate Shrine Over a Mouse Hole,” retells the life of a friend through interviews of mutual acquaintances. The essay is a meditation on death, and art’s ability to speak on the artist’s behalf. Wojnarowicz struggles to reach a conclusion; he fears that his own death will silence his voice. “I am glad I am alive to witness these things; giving words to this life of sensations is a relief. Smell the flowers while you can,” he ends. Smelling the flowers means finding the courage to commit to pleasure despite the forces competing for our health and for our love. It’s realizing that the only way forward, is through. With courage, with care, with passion, and with love.

Editor-in-Chief (Volume 48 & 49) | editor@themedium.ca — Liz is completing a double major in Chemistry and Art History. She previously served as Features Editor for Volume 47, and Editor-in-Chief for Volume 48. Liz is extremely excited to have spent her time as an undergrad at The Medium, and can’t wait to inspire others and be inspired in her final year at UTM. When she’s not studying, working, writing, or editing countless articles, you can find her singing Motown hits at her piano, going on long walks by the lake, or listening to music. You can connect with Liz on her website, Instagram, or LinkedIn.