Lecture Me!: Reforming police culture for police practices in Canada

Professor Julius Haag explains the ‘why’ and ‘what now’ behind a declining trust in police services through the lens of policing in the Greater Toronto Area.

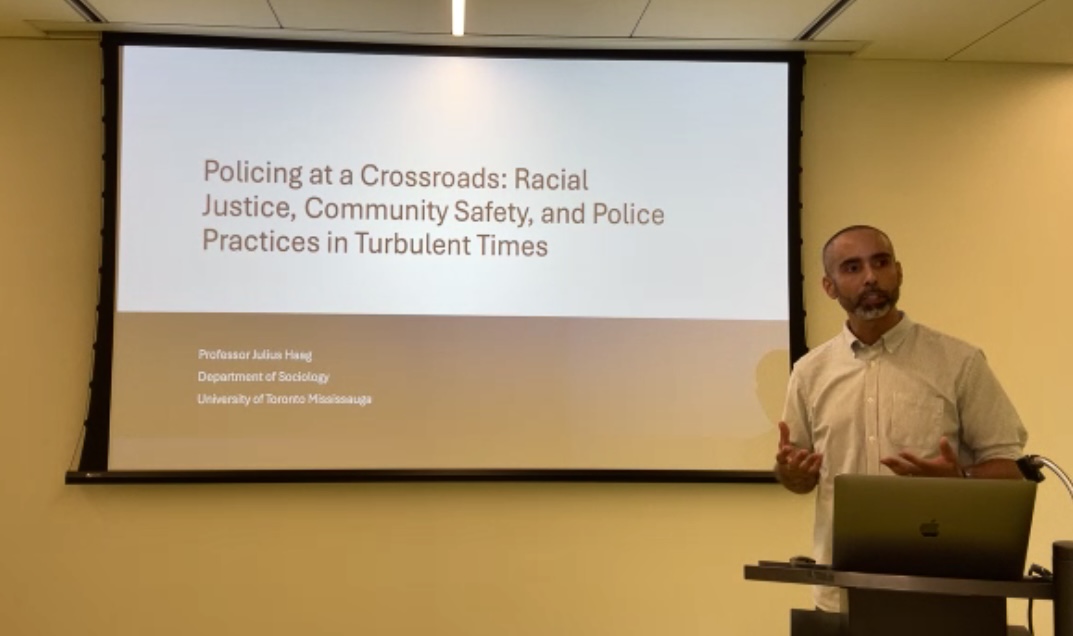

On September 10, Julius Haag, a professor of the Department of Sociology at the University of Toronto Mississauga (UTM), hosted his presentation at the Hazel McCallion Central Library about policing issues in the Greater Toronto Area titled, “Policing at a Crossroads: Racial Justice, Community Safety, and Police Practices in Turbulent Times.”

The presentation examined the evolving role of police officers in response to the public’s declining trust in law enforcement and discussed ways to restructure the police’s role to ensure community safety.

Professor Haag stresses that the role of the police is complex. Police officers provide various services such as mediation, dispute, and referral that require significant discretion. “It’s expected that no matter what your problem is, you can call the police, and they will come to your problem,” Professor Haag explains. However, as police officers are entrusted with significant authority and lethal power to perform their duties, the misuse of discretion is eroding the public’s trust in law enforcement.

Racial disparities in focus

Police brutality and racial profiling are not only issues in the US but they receive less attention in Canada, partly due to the lack of systematic collection of race-based data, according to the presentation. However, instances of involuntary contact—which refers to an encounter experienced by a member of the public that an officer initiates—have revealed significant racial disparities across Canada. In these interactions, officers may ask for information that potentially reveals a person’s unconscious bias.

“It’s interesting how widespread these practices are,” Professor Haag comments. According to Professor Haag, these disparities were more pronounced in affluent and predominantly white neighbourhoods, which “suggests that Black people found in those areas were deemed to be out of place.”

The presentation revealed that recent datasets express that Black people are three times more likely to be stopped than their white counterparts in Canada. Young Black men aged 18 to 24 are 2.5 to four times more likely to be stopped than the Canadian population would predict. Black people are also more likely to be stopped from proactive police efforts such as traffic stops and street checks.

Following the emergence of this data, police argued these outcomes result from a higher population of Black people living in higher crime neighbourhoods with intensified surveillance.

Professor Haag introduced the effect of race and place to counter this dismissal of officers’ unconscious bias. According to Professor Haag, the effect of race and place refers to how racial prejudice and a geographical location amplify bias against marginalized communities. “There is a patterning of suspicion that’s associated with the location that individuals are found and police associations of danger or suspiciousness.”

Professor Haag also collaborated with sight agencies to develop a body of evidence on the use of force. Local datasets from the Special Investigating Unit found Black people were nearly 20 times more likely than white people to be shot and killed by the police in Toronto.

A dataset from 2018 by researchers from CBC News found that between 2018 and 2020, 68 per cent of people killed in police encounters suffered from some form of mental illness. Professor Haag believes these results pose serious concerns with the rising reliance on police as first responders, especially for marginalized communities and those who suffer from mental illnesses.

Community safety as a public concern

While the public relies on the police, the police also depend on the public. Professor Haag highlights how law enforcement often seeks the public’s assistance, whether through reporting problems or providing information for investigations. In this way, the public becomes co-producers of community safety, but this cooperation can hinge on the public’s trust in the police.

Professor Haag mentions recent scholarship from the past 50 years which reveals what motivates the public to trust the police, and it hinges on procedural justice. We decide whether or not to trust the police based on how fairly we are treated.

Professor Haag examines the importance of procedural justice with the example of disputing with your neighbour, “We call the police; they speak to my neighbour, and they get all the information from them and listen to their views. They say, you know what Julius… they’re right, you’re wrong. I don’t care what you have to say. Have a good afternoon.”

Professor Haag highlights that if we believe that police treat us fairly, we are more likely to accept and abide by the outcomes.

In contrast, procedural injustice contributes to a climate of distrust and unwillingness to contact the police in times of need which pushes the public to feel the need to tackle their own problems. Ironically, abuse of discretion paired with procedural injustice creates a paradox of “over” and “under” policing for racialized people.

The tension between the public and the police creates turbulence for both public and police goals. Professor Haag explains that “the pervasive and long-standing distrust between many racialized communities and the police represent a fundamental barrier at [improving] the [relationship between] the police and community and ultimately fostering the kind of trusting relationships the police rely on to exercise their mandates.”

Restructuring police culture becomes crucial in revitalizing security in Canadian communities.

The power of acknowledgement

Professor Haag advocates for the development of several policy responses and the reforming of police culture as a powerful effort for moving forward. “We need data collection so we can trace, track, measure and understand the extent of racialized disparities in our legal system. It then needs acknowledgement from our elected officials that these are real problems, and the police are taking accountability for these issues.”

“We are well beyond the point of denial,” Haag asserts, delivering a grounding affirmation near the end of his presentation. “We’re well beyond the point of saying that this is an American problem, that this is not a Canadian issue, that this is an isolated problem. It is a systemic issue through our criminal legal system…These are areas where acknowledgement, recognition, and taking accountability are key mechanisms.”

Yet Professor Haag is wary of current movements to better police training. He emphasizes redefining the role of the police, “When we think about defunding and de-tasking, this involves a systematic review of what the police do, which emergency calls can be resolved by a better service? If such agencies don’t exist, can we create them? If those agencies do exist, can we fund them appropriately?”

Rather than better training, Professor Haag wants to restructure Canadian society in a way to spread the burden on police officers to more suitable special agencies

“We see police responsible for much of our public response issues like homelessness, mental health, substance abuse, and the effects of concentrated power.” Professor Haag’s proposal does “not [envision] a society that is free of police, but one where we minimize the need for police by finally addressing decades of concentrated social infrastructural problems that for far too long have been the domain of the police.”