Language is civilization’s first weapon

Words are powerful, and we get to decide whether they are weapons of pain or tools for peace.

In all my psychology classes, language’s role in shaping the course of human existence, everything from our minds to society itself, cannot be underscored enough. In our evolutionary history, the advent of language — whether spoken or written or signed — marks the pivotal realization that certain words stitched together to form sentences could bridge otherwise insurmountable barriers between minds, tribes (or nations), and creeds.

With the power of communication at our tongues, diverse perspectives and abstract ideas galvanized humanity towards a newfound sophistication, allowing us to transmit culture, nurture collective identities, and form alliances. But, somewhere between sharing stories around the campfire to creating new writing systems, words slowly transformed into the art of rhetoric, the rules of persuasion, and the basis of deception.

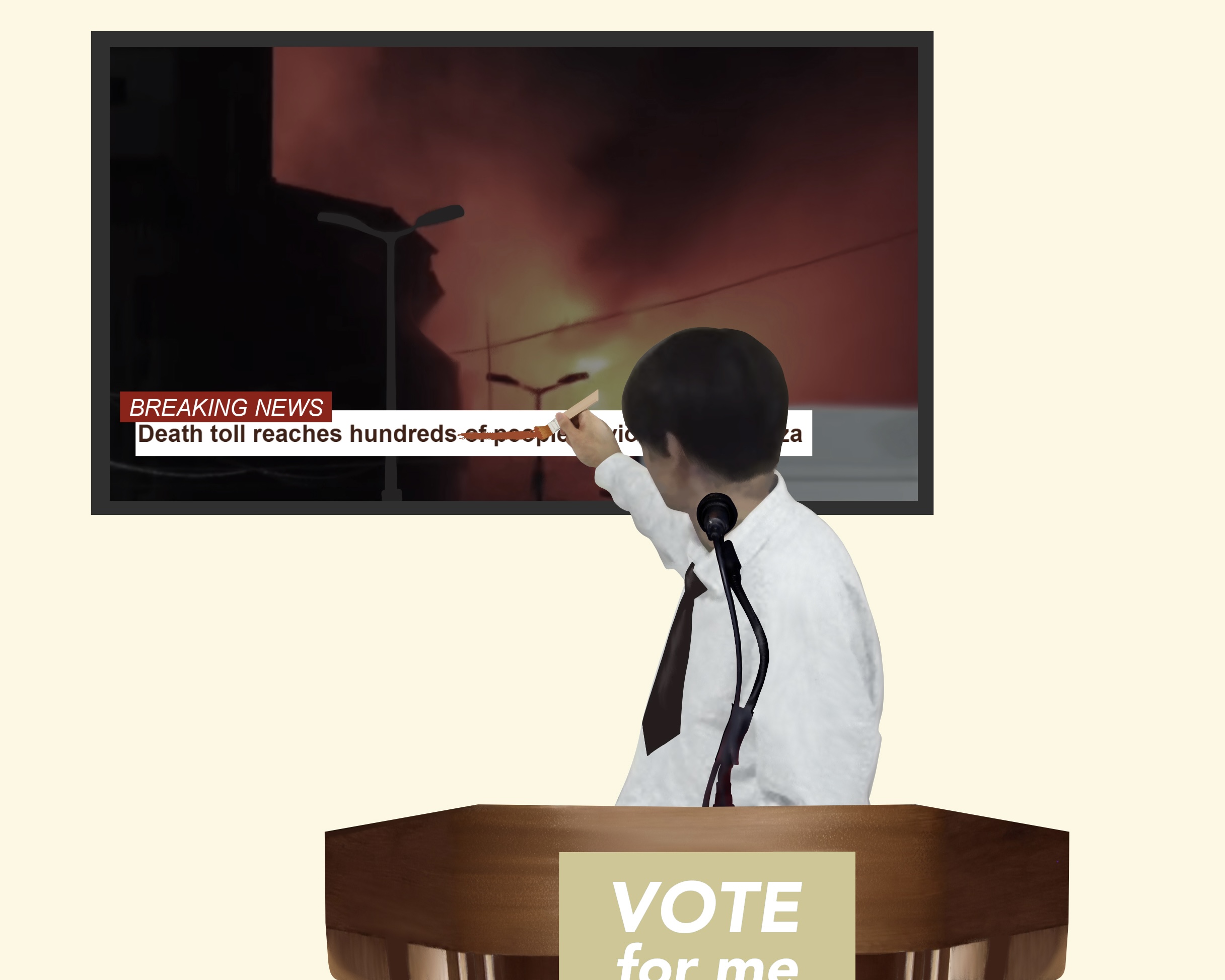

Words as weapons

Words are critical to our evolutionary past. But they are even more important to our current moment. We live in an age where insults can be hurled across continents within mere seconds (if one’s Internet speed allows); where governments, institutions, leaders, and even community members can wield language to dehumanize victims of colonial and imperial violence and, in turn, celebrate the systems of oppression they are positioned to benefit from.

So, how exactly is language abused to distort the realities of our world?

People know words have weight. The conversation about Israel’s illegal occupation and ethnic cleansing of Palestinians is reduced to a palatable afterthought for many, especially those that have a robust social media presence and feel the pressure to comment on such matters.

Sure, the history of the Middle East is “complicated,” but not more or less complicated than any other history. You see, in using words such as “controversial” or “complicated,” to describe the “situation” in the Middle East, language becomes an instrument to minimize and deflect the suffering and colonial violence inflicted on Palestine. And for what? To protect our conscience?

Words leave an impression, and the impression left by our current discourse surrounding the Middle East is that colonialism is a thing of the past. We can use words to distance ourselves from the direct realities of the colonial violence our governments enable. But that does not mean we are spared of the moral weight of living in an interconnected world of our making, where our actions—or lack thereof—are indirectly tied to the oppression of others not very different from us.

And let’s not forget the “civil wars and famines” raging on in Sudan and the aftermath “humanitarian crises” of Tigray in Ethiopia. These are technically correct terms, but in my opinion, they fail to acknowledge the political and economic realities of these countries. Unsurprisingly, these are tied to the colonial canvass of Africa, as well as the proxy nature of many of these so called “civil wars.”

My main concern is why we feel the need to use such covert and depoliticizing language to describe and understand something that is indeed deeply and irrevocably political. By depoliticizing, I mean using language that hides or distracts from the fact that these are man-made wars, genocides, famines, and conflicts. The suffering and, by extension, resilience of oppressed communities is political because it didn’t happen in a vacuum. In fact, the very act of using depoliticizing language is itself political because it could signify cultural ignorance, which, in my opinion, if carried on, is siding with the oppressor.

The science of dehumanization

Multiple research studies in psychology and even neuroscience have observed the influence dehumanizing words has on how individuals are treated. We all know what dehumanization means in colloquial terms. But what does science tell us?

It is easy to spot dehumanizing language, such as animalistic descriptions of people. Psychologist Florence Enock, in her analysis of historical data, found that during historically salient periods like the persecution and extermination of Jews in Nazi Germany, humanizing language was three times more common than overtly dehumanizing language.

This is a contradiction because, normally, we’d think dehumanization is obviously morally depraved and easily recognizable.

But Enock suggests otherwise and illuminates the exact insidious nature of dehumanization. There is no causal link between dehumanization and the explicit and violent harm endured by so many around the world. Instead, dehumanization “increases people’s willingness to endorse harm,” says Enock. A cultural script for dehumanizing certain people over others simply makes it easier for some to sit on the sidelines and watch as others suffer an entirely avoidable onslaught of massacres, famines, genocides, and other countless forms of violence, direct and indirect. It’s essentially the by-stander effect on steroids.

Through her work, Enock suggests that the reason humanizing language is more common in times of oppression is because “dehumanization needs to be understood as something much broader than animalistic name-calling or objectifying. It’s a philosophically wider blindness to the fact that someone may be a human being with subjective experiences […] it’s a fundamental ‘moral misrecognition.’”

A responsibility to each other

Language is not the enemy. And it’s more than just an asset. It’s a tool to chisel out the reality that we want for each other and our shared future.

In 2022 during a public talk, the Indian-British novelist Salman Rushdie was stabbed fifteen times, which left him severely wounded and in hospital for months. Rushdie, through his provocative criticism of militant and fundamentalist religion, has come to symbolize the intellectual freedom and the power of stories in times of division and uncertainty.

In his Masterclass, Rushdie says that “we are the only creatures who does this unusual thing of telling each other stories to try and understand the kind of creatures we are.” As such, we have an immense and often overlooked responsibility to harness the potential of this power. We can choose to use language to erupt in anger and to affirm our echo chambers. Or we can harness its unifying power.

We forget the people less fortunate than us are also mothers, fathers, daughters, sisters, sons, brothers, lovers, and friends. We forget that what separates us from them is sometimes mere geographical luck, or something equally arbitrary. It’s time that the language we use and the stories we tell remind us of our shared humanity.

Opinion Editor (Volume 51); Associate Opinion Editor (Volume 50) — Mashiyat (Mash) is a third-year student studying Neuroscience and Professional Writing and Communication (PWC). As this year’s Opinion Editor, Mash hopes to use her writing, editorial, and leadership skills in supporting student journalism in the essential role it plays in fostering intellectual freedom and artistic expression on campuses. When she’s not writing or slaving away at school, Mash uses her free time cooking cultural dishes, striking up conversations with strangers, and being anxious about her nebulous career plans. You can connect with Mash on her LinkedIn.