Going beyond chalk-and-talk

Exploring the difference between active learning and traditional lecturing and how it impacts student learning.

When you picture a university-level math class, you might imagine something like a scene out of Good Will Hunting—a big blackboard with nebulous math scribbled all over it and a lecturer planted in front.

However, University of Toronto (U of T) Mississauga (UTM) students are finding themselves in math courses that break from the traditional ‘chalk-and-talk’ style of teaching. Non-traditional pedagogies such as active and inquiry-based learning are student-centred ways of teaching.

Rather than treating classes as a time for one-way knowledge transfer from professors to students, these non-traditional pedagogies prioritize student engagement and the learning process. Instead of spending the bulk of lecture time listening to the professor and taking notes, students might arrive at class having read some of the lecture material and are encouraged to solve and explore problems during class, often with their peers.

UTM was the first campus of U of T to pilot active learning, and it has since been widely embraced across all three campuses. Many students’ first experience with university-level math is now in an active learning environment.

This departure from traditional lecture styles at UTM reflects the research that points to traditional lectures being an ineffective teaching method. According to a PNAS research article, students in classes with traditional lecturing were 1.5 times more likely to fail than students who were in active learning classes.

According to Professor Jaimal Thind, a teaching-steam math assistant professor at UTM, “Getting up and talking for two hours and making everybody listen is not the best way to teach.”

While practicing math occurs mainly outside of the classroom under traditional pedagogies, active learning enables professors to incorporate content inside the classroom. Assistant Professor Micheal Pawliuk, also a math teaching stream instructor, explained that learning math is “more than just facts and techniques,” and that “it’s about perspective and practicing.”

Classes that de-emphasize pure lecture and incorporate more practice and exploration can better emulate and support the learning process. Professor Thind compares learning math to learning an instrument—while listening to an instructor can be helpful, it is impossible to learn to play the instrument without practicing. Similarly, practice is a core tenet of learning math that cannot be divorced from the learning process.

Unfortunately, math maintains a bad reputation for many people. Whether it stems from the canonical experience of crying over long division as a child or feelings of inadequacy in the subject, many people approach math with fear and repulsion, especially in the context of tests. This is part of a phenomenon known as ‘math anxiety.’

Some non-traditional teaching methods and course structures might alleviate some math anxiety. Courses that use mastery-based grading, where students have multiple attempts at term tests and can master topics at their own pace can reduce the perception that tests are threats.

In an even more radical move, some courses, such as MAT344 (Introduction to Combinatorics) have done away with assignments and timed assessments entirely, opting instead to grade portfolios of students’ work over the semester.

Moreover, in many student-centred pedagogies, students work through problems with their peers during class. Thind describes the experience of math as “being stuck most of the time and coming to terms with it,”—a foreign and disheartening feeling to a student who is new to math. Working on problems in groups “helps [students] feel less isolated,” Thind explained. “There’s something reassuring about ‘I’m stuck, but so is half the class.’”

Although the evidence suggests that these non-traditional pedagogies can improve students’ performance, students have mixed feelings about them. Rakshaan Koodoruth, a fourth-year student completing a double major in mathematical sciences and economics, shared that “for more challenging concepts, I would much rather have active learning.”

However, Adil Billah, a third-year student double majoring in mathematical sciences and physics, prefers the opposite and instead, “normal lecture styles.” He explained that he found it more helpful and rewarding to see “long derivations instead of just doing exercises yourself.”

While there has been a major shift towards active learning in UTM math classes, it has its weaknesses. Professor Pawliuk explained that active learning courses can involve many micro-components, including readings, weekly quizzes, and assignments. Pawliuk admitted that this approach “doesn’t always set things up well for sitting with big ideas or exploring bigger topics.”

The advent of ChatGPT and generative AI is also changing the educational landscape. Plagiarism is becoming increasingly difficult to detect in math assignments, and instructors are forced to adapt. While there had previously been a push to have assignments and non-timed assessments make up more of the course grade compared to tests, Professor Thind noted that this move is quickly being reversed in some classes.

As the educational environment and research on math pedagogies continue to evolve, so will the math courses at UTM. “We want to capture [students’] sparks,” Professor Pawliuk said, “and help them ignite.”

—

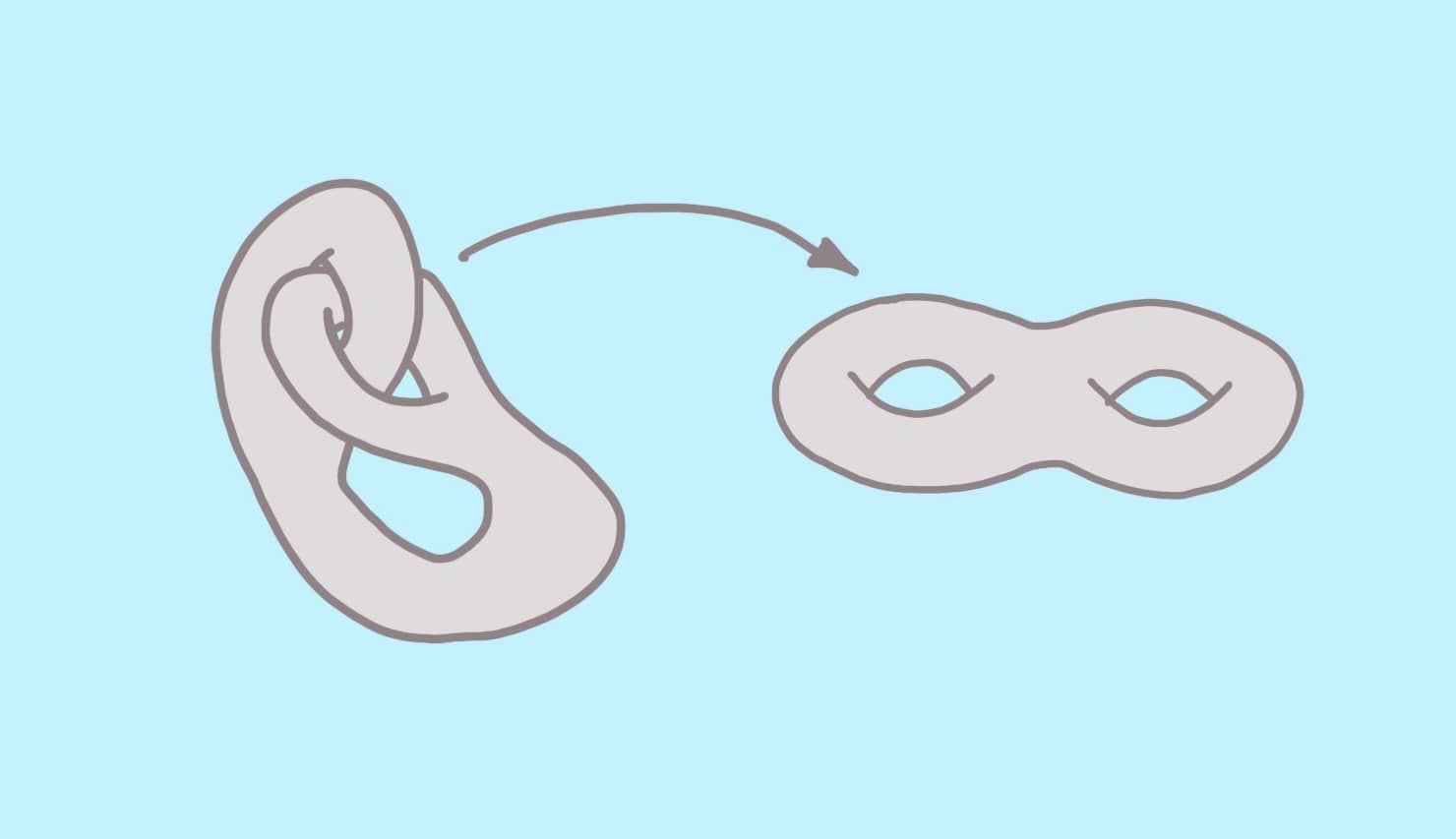

Bonus! A bit of math for you from Professor Thind. In the image above, see if you can transform the surface on the left to the one on the right by stretching, shrinking, pulling, and pushing the surface. You CANNOT tear, cut, or rip the surface.