Censorship is evolving, but so is journalism

An interview with journalist Emma Paling on fostering hope in an age of distorted realities.

From a young age, I remember wanting to write — with the vague dream of being a journalist always looming over my shoulder — even as I flung myself into the sciences for hopes of a better career. Now in my third year of university, writing is no longer relegated to a hobby. It shapes my career decisions and my civic engagement. But though I love it, 2024 has taught me that the journalism industry I want to work in is not without its flaws.

The pitfalls of mainstream media

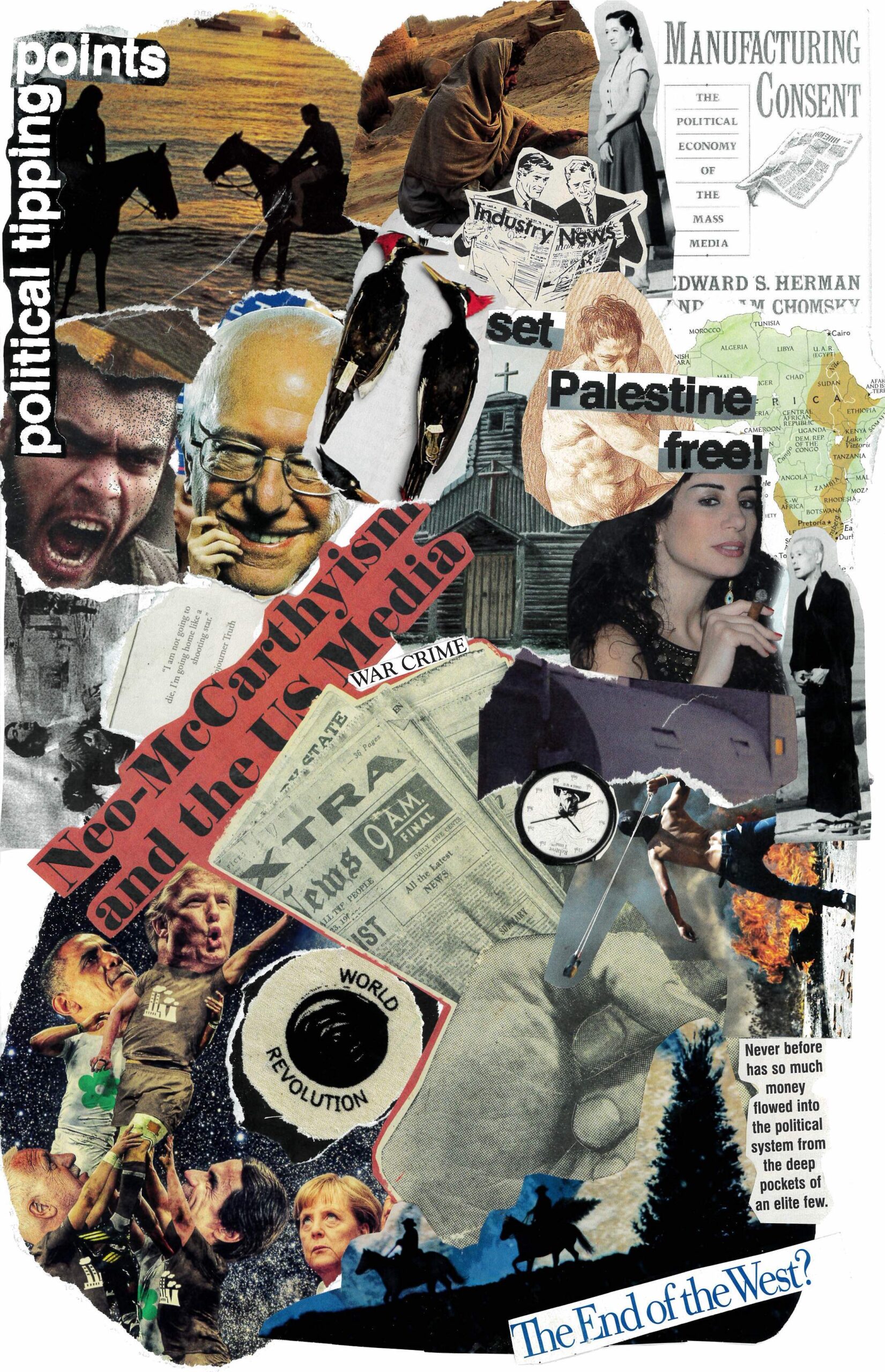

Although public trust in centralized mainstream media — such as the New York Times, the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC), the Toronto Star, and Global News — has been declining, these platforms remain at the forefront of shaping public perception, especially during politically important moments such as elections and other globally relevant events. As corporate-owned establishments, these news agencies have an unshakable grip on the information access and decision-making of ordinary citizens. Politically or financially motivated pressures, the concerns of the corporate elite, and the status quo influence these news organizations to report certain things in certain ways.

Even smaller platforms like the Huffington Post are driven by a corporate model and informed by industry norms. Journalists, whose responsibility is to deliver critical, empathetic, and accurate reporting, often work under difficult conditions where their time, resources, and access are restricted by demands to increase virality and digital traction, while adhering to simplistic, partisan-pleasing neoliberal narratives.

This is heartbreakingly evident in the Canadian media’s coverage of Israel’s genocidal violence on Palestinians in the Gaza Strip, West Bank, and neighbouring countries following the October 7th Attacks by Hamas. In writing this article, I had a conversation with Toronto-based journalist and writer Emma Paling, who has done exceptional investigative reporting on the media’s treatment of Palestinian stories.

“Colonial bias” and slow violence: the media and Palestine

How much propaganda and lies can be packed into a headline? In the month following Israel’s retaliation against Hamas, Paling investigated anti-Palestinian bias in how editors and directives at CTV News, CP24, and BNN Bloomberg — all owned by Bell Media — “guided” their journalists to cover stories about Palestine. Not only were more Israeli voices featured, but mentions of Palestine as a country and identity, and critical narratives about the extent of violence in Gaza were sanitized or simply censored. For example, coverage of protests with chants for liberation, statements on the exact Palestinian death toll, and the provision of important context on Israeli-Palestinian history — especially ones that focused on Israel as an occupying power — were met with unjustified scrutiny and censorship.

What was particularly appalling to me was another report by Paling where she reveals the extent to which the CBC normalizes sanitized language, even when journalists resist such editorial decisions. Not only did the CBC use more sympathetic language to describe Israeli casualties and sentiments, but the CBC responded to complaints over their editing choices by asserting that “Israel carries out its killings ‘remotely’ instead of face-to-face,” which “does not merit the terms ‘murderous’ and ‘brutal.’” At the time, Israel had killed more than 22,600 Palestinians. Unbelievable.

There’s multiple reasons for this, but when asked why the Canadian media — which prides itself on journalistic integrity and press freedom — has a glaring double standard, Paling says: “there’s a long standing colonial bias in Canadian newsrooms. Canadians don’t want to see themselves as the bad guys.” And while unmarked graves at former residential schools have forced the media to confront that our nationhood is birthed upon Indigenous cultural genocide, “there’s still resistance to using that [reckoning] to look at the whole country, to look at Canada’s influence in the world, and the fact that our country is allied with such a violent occupying power such as Israel.”

Paling goes on to say that, even though corporate-owned media have done ground-breaking journalism, when it comes to “Israel and Palestine issues, and on other issues too I am realizing, such as politics in general, there’s actually a lack of rigor. There’s a whole history of occupation that people just don’t want to talk about.”

From casual conversations with her friends to observing the industry climate, Paling also claims that unjustified and excessive editorial scrutiny of Palestinian stories is exhausting for journalists who yearn to write critically. CBC journalist Molly Schumann wrote an article for The Breach, an independent Canadian media outlet, where she identified that many writers feel pressured to self-censor their writing to uphold CBC’s clear bias against fair coverage of Palestine.

Schumann observes that some of these pressurizing conditions include, but are not limited to, CBC overly editing or cancelling interviews from the Canadian-Palestinians compared to Israeli interviews. Other examples include censoring mentions of genocide, whitewashing western-backed Israeli violence, unwarranted accusations of anti-Semitism in the newsroom, and secret blacklists for passionate pro-Palestinian speakers. I urge you to read Schumann’s original article, as it interweaves the relevance of her Jewish ancestry and career interests at CBC with her fight against the media’s complicity in delegitimizing genocide.

In my opinion, the media’s treatment of Palestinian stories is tantamount to “slow violence,” an idea elucidated by Norwegian sociologist Johan Galtung that describes human suffering to be the result of invisible and indirect violence. Majority of human lives suffer not at the hands of violent gunmen or militias, but at the behest of oppressive systems of inequality and greed that our politicians and the status quo happily uphold. The media, lobbying groups, and the religion of money and power are all forms of slow violence that kills behind closed doors and in expensive suits, hiding behind whatever guise or explanation that pleases the systems that benefit them.

Is there a possibility for reform and hope in journalism?

Reform starts with accountability. And there has been none. Since the conflict, talk radio shows and articles have carelessly spewed many dehumanizing and incorrect statements. One radio station at Global News said that students at pro-Palestinian encampments in Montreal taught children to use weapons to dig tunnels. Canadians for Justice and Peace in the Middle East (CJPME) demanded a correction of this absurd statement from the regulators of the show, but nothing was done since the comment did not meet an arbitrary threshold for what is considered racist. “The bar is so high to be considered hateful content that you can basically get away with total lies and implying racist things, and there’s no accountability. It’s been shocking,” claims Paling.

It’s certainly disturbing knowing that Canadians are unaware of the terrible reporting that takes place inside newsrooms and of the editorial decisions, whether spoken or unspoken, that shape public opinion and policy. Canada and the US are living through a politically consequential period: global consciousness is rising about how Western greed and violence are deeply entrenched in the Global South and third-world countries.

Yet, there is little to no possibility of reform in mainstream news. Not only is there a complete lack of accountability, but some editors have outright “refused to correct things that were proven to be incorrect later on,” says Paling. Amidst the many colours of censorship the media has enabled, a future of truth and justice on behalf of media corporations looks unlikely.

However, I think there is something important to be learned here: the questions and stories our mainstream outlets stifle or censor are precisely the questions and stories we should be seeking. If anything, the injustice perpetrated by prestigious outlets like the CBC and Global News have simply told us where to look. In distorting the truth, they told us where to find it.

Alternative media: a beacon of hope

Independent (indie) media, as evident in the name, is not corporate-owned and much smaller in scale. This means that journalists have more freedom and time to pursue critical and original stories, ones that are not subject to elitist and profiteering pressures. Paling is just one of a handful of journalists who have written about Palestine with the sensitivity and depth lacking in mainstream media: work which she says could only be published on leading indie platforms like The Maple, The Breach, and The Grind.

Mainstream platforms regularly dehumanize minorities. Even when journalism is well-intentioned, coverage can lazily feed into stereotypes to communicate information. For example, Palestine needs to be talked about independent of its subjugation under Israeli occupation and suffering. What about the stories of positive resistance, Palestinian culture, and achievements? And not just achievements “in spite of horrible conditions” or “unimaginable suffering.” Indie media has spearheaded such stories, and those of other demonized minorities too, such as Indigenous Peoples.

“I think we’ve really played a huge role in informing Canadians, and demonstrating the power journalism has when we are not falling into these lazy and cowardly journalistic conventions,” says Paling.

Though indie media has made strides, it’s important to point out that the rise in podcasts — which are forms of independent media — and conservative indie outlets coincides with the rise in right-wing rhetoric that has only added to a climate of information pollution, especially in an age where many lack media literacy.

However, these small-scale platforms, largely funded by local and loyal readers, continue to be voices of empathy and reason. Reporting on protests and rallies, reading in between the lines of mainstream rhetoric, investigating our country’s shameful complicity in building weapons that bomb the civilian-packed streets of Gaza, and amplifying minority voices are just a few things indie media has excelled at. Indie media can write about these things because their readers demand it. And their readers, according to Paling, are overwhelmingly Gen Z and millennials.

“I think I can say without a doubt that over the course of the genocide in Gaza, the Canadian independent media has absolutely proven its worth. We have been at the forefront of the conversation and setting the agenda, while the traditional outlets are following us,” says Paling, exuberantly.

Interconnected struggles, interconnected hope

Faulty reporting is not limited to Palestine. The student-led mobilizations in Siberia calling for systemic reforms, the crises in Haiti, resource and labour exploitation in Congo , or the mass suicide of Sudanese women and girls to avoid rape amidst the ongoing civil-proxy war have all gone grossly underreported.

Where is the critical narrative that such displays of global suffering and violence are, in part, products of western exploitation and funding and not just isolated problems? Why is our media failing to explore the interconnected realities of Palestine, Venezuela, Congo, Haiti, Sudan, and many more?

It seems to me that the mainstream media is grossly hesitant in asking uncomfortable questions about underlying issues, because the same elitist conglomerates that benefit from such displays of slow violence are the same conglomerates that fund these media companies, essentially buying and selling narratives. But where traditional media has failed, indie and student publications, have succeeded.

In December of 2024, the Israeli government, supported by Jewish-American lobbying groups, motioned to invest a whopping $150 million into the country’s propaganda machine, which aims to abolish anti-Zionist and leftist views from social media, university campuses, and foreign media platforms. In Israeli newspapers, this investment is framed as simply supporting “public diplomacy abroad.”

Money speaks volumes. That $150 million is a cry of desperation against the much louder voices of humanity that have protested, boycotted, and condemned Zionist propaganda since even before October 7th. If the urgent truth-telling done by independent sources was failing, then such money would not be needed. If the situation was hopeless, the propaganda would be unnecessary.

In a touching article for The Toronto Star, Egyptian-Canadian journalist Pacinthe Mattar says that when she held a vigil for murdered journalists in the Middle East, the only reporters that showed up to cover the event were from student publications like The Eyeopener — Toronto Metropolitan University’s (TMU) newspaper — and the Review of Journalism, another TMU-based magazine.

In the summer of 2024, pro-Palestinian encampments took to the field of King’s College Circle to protest U of T’s complicity in the genocide. The Varsity rigorously reported on these encampments, as well as other Palestine-related happenings, with consistency and a student-focused lens. The Varsity is currently creating a database of resources and best practices to enhance campus coverage of such events.

Against the flood of heartbreaking images of global events, the hypocrisy of our institutions, and the inadequacies of traditional media, indie media is a beacon of hope for me, Paling, and many others. In the past, I read the CBC and The New York Times. Part of me still wants to have bylines on these platforms, but the truth is, I am incredibly proud to write for student publications like The Medium and The Varsity where sensitivity and student-centered discourse take precedence over pushing certain agendas or succumbing to the simplistic appetites. This is where my hope lives.

Writing hope into our futures

We live in an increasingly frenetic culture. Everything from our lives in real-time to the fast-paced, bite-sized, algorithm-driven world of social media fails to capture the depth of experiences. It also doesn’t equip us with the skills to digest information in the digital age with nuance and perspective. We scroll, we read, we hear the cries of orphaned children and wailing parents on our screens, and amidst it all, it’s too painful to remember that what’s on our Instagram feeds isn’t just “content.” It’s real people with real sorrows and real happiness.

Mainstream journalism has noble intentions, but amidst the rush to cover stories, it prioritizes quantity over quality, neglecting a lens that humanizes. In my experience, instead serving its democratic purpose, mainstream sources have left readers misinformed and polarized by simplistic narratives and shy reporting.

On the other hand, it doesn’t seem like indie media will overtake mainstream sources, but there is a generational pattern among indie media consumers, namely young folks. “That’s a source of hope,” says Paling, “because it’s younger people who are really caring about this [despite] professional and social consequences; so the fact that young people are willing to be vocal about this, and post it on their social media, and be proud to support Palestinian solidarity, gives me a lot of hope.”

Journalism and writing are also spaces to cultivate rage and hope in an intentional way. Journalism that can stand its ground gives shape to hope. It gives hope to a future where hope is not an imagined and fickle emotional desire for a better world, but an actionable reality. But only if we can see through the poison of corporate media.

Without the shared hope journalism gives us, we risk devolving into passive nihilism, which threatens any social justice progress we have made so far. The past year has shown us that independent journalism is for the people, and by the people. That is where my hope is.

Opinion Editor (Volume 51); Associate Opinion Editor (Volume 50) — Mashiyat (Mash) is a third-year student studying Neuroscience and Professional Writing and Communication (PWC). As this year’s Opinion Editor, Mash hopes to use her writing, editorial, and leadership skills in supporting student journalism in the essential role it plays in fostering intellectual freedom and artistic expression on campuses. When she’s not writing or slaving away at school, Mash uses her free time cooking cultural dishes, striking up conversations with strangers, and being anxious about her nebulous career plans. You can connect with Mash on her LinkedIn.