“Black like her father”

A reflection on the coupling of Blackness and anger.

I couldn’t tell you the details of why my 13-year-old-self stomped angrily into my house that day. I couldn’t tell you what the girls on the street said to bother me. All I can remember is that they directed a snide, racially-motivated remark at me, were surprised when I clapped back in Arabic, and pushed me into a rage that brought all my previous hurt to the forefront.

Upon seeing the force with which I shoved the door, my parents urged me to tell them what was wrong. After repeating “I am just done with these people” some 10 times, I obliged and recounted what happened. I waited for comfort from my parents. To my surprise and—at the time—dismay, my father broke into guffaws. My father’s guffaws became shouts. Then he held me by the shoulders and directed his shouts to snap me from my rage-infused stupor. “Some stupid girls called you some stupid name and you get this upset? Do you know how many people called me names? Do you know how many people hated me just because I was Black? Do you think you would be living in this nice house going to your nice school if I kept on crying about it? Stop being dumb!”

—-

Growing up, I knew two sides of my father.

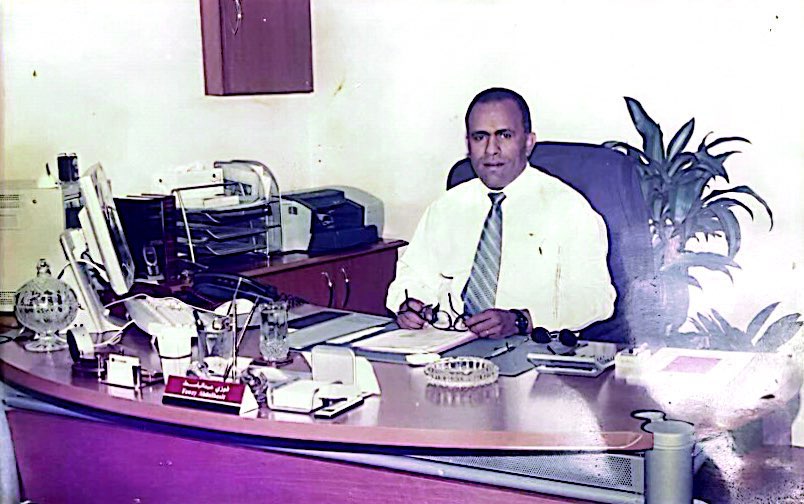

I knew the angry man. I knew a man so intense that schoolteachers were afraid to have parent-teacher meetings with him. A man who valued diligence and righteousness above anyone else’s feelings. It became clear to me that this is the way the world perceived him: an imposing and intimidating figure. I remember once I had a conversation with a person who didn’t know that he was my father and identified him in conversation as the “big Black man.” For the sake of irony, my father is a man of medium build, not taller than 5’6”.

But he was a lot more than what people made him out to be. I knew him as a man who fascinated me with all the facts and culture he knew. I knew him as a man who told many stories about the world, little about his life, and just wanted me to know more. I knew him as a man who sometimes got teary-eyed. I knew him as a slightly funny, certainly impulsive man with hopes that he would leave his children more prepared for the world than his father did.

But my father did not know how to have conversations with me about anger, nor did he know how to have conversations about being Black. Still, being angry and Black was a label that I felt swallowed me for much of my life. A label that made me feel like a pariah, an untouchable of sorts.

When I was a child, my Blackness was not something that I realized for myself. Rather, it was something that the world made me aware of. My Blackness was something that I learned through being othered, both subtly and outwardly. On the basis of taking after my mother’s beige skin, my siblings did not understand my experience, nor did my mother. It became isolating, so I learned to fall on my rage like my dad fell on his.

My dad’s anger was a law of nature that I did not question. But I did try to infer what it meant to be Black growing up. When I would try to decipher what his experience was growing up Black and working class in Egypt, my father would be mostly quiet, sometimes agitated that I pestered him a little too long for his liking. “Things were okay, why are you asking?”

But as my father grew older, he mellowed. And his lips loosened. In sporadic spurts, my father gave me tidbits of his younger years as a Black man. When I told him I couldn’t land a waitressing job, he told me that it was similar for him too; when he worked at a restaurant, they did not allow their Black staff to work as servers. On another service job that he took up during university, people often treated him with inferiority just because of his skin. Perhaps this is why he felt strongly against me getting anything “lower” than a desk job. One day, my father talked to me about the importance of having mentors in my career. Unprovoked, he admitted, “oddly enough, none of [my mentors] were Arab or Egyptian.” When I asked him why that was, he said, “I guess they just found me too angry, and they didn’t understand why.”

—-

My father released me from his grip, and I would soon be in my room. Tears were still in my eyes. My shock surpassed my anger. At that moment, because my father did not give me the comfort that I wanted, I thought he did not understand. How could he let his anger overtake his duty to soothe my pain? Although he couldn’t communicate it, my father did understand. He just wanted to prepare me for the world that he knew. And the world my father knew would not care for my feelings.