What binds art and science together

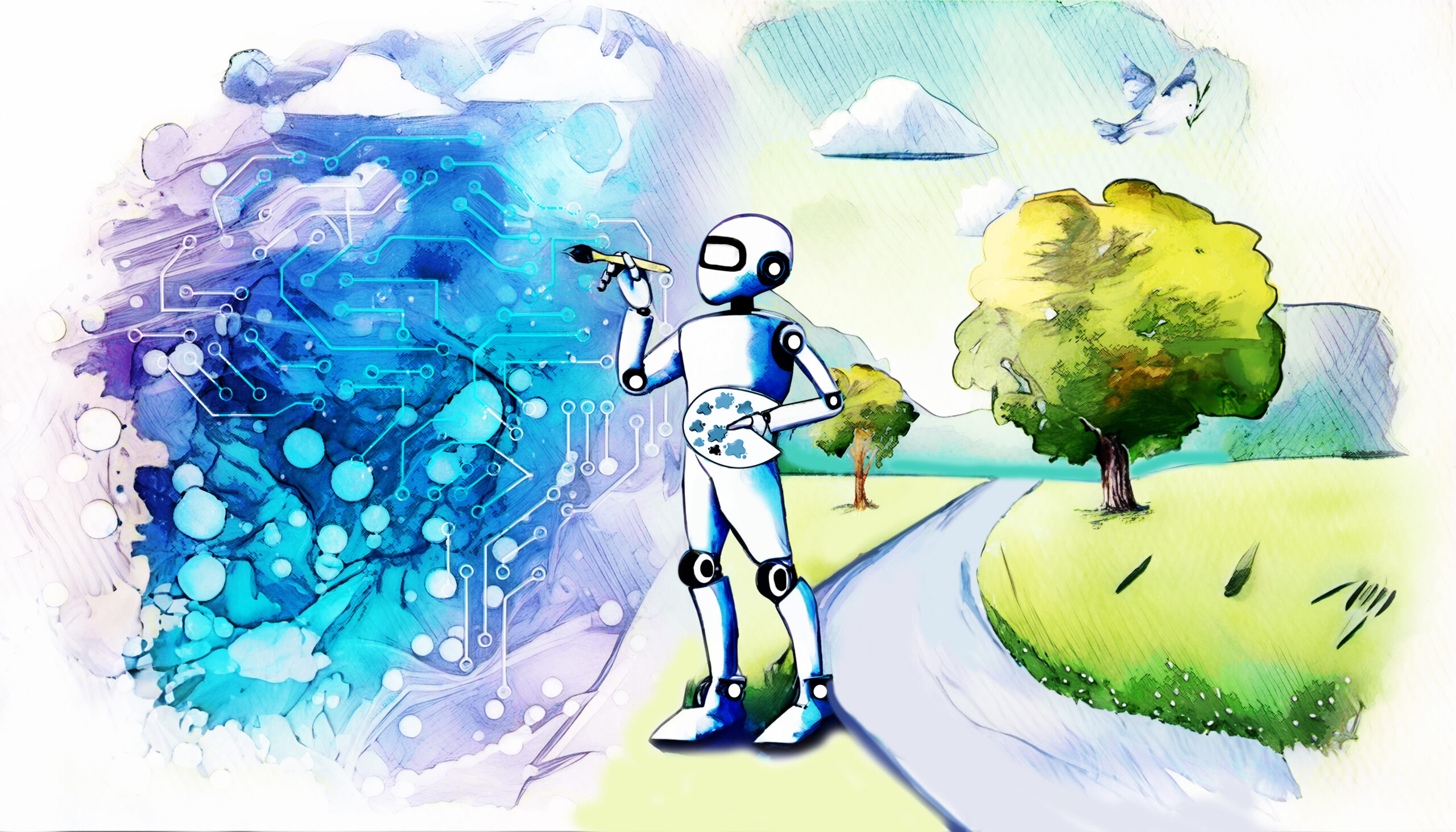

Imagination is the essence of what ties artists and scientists together in a world that continues to emphasize their differences.

I came to U of T to study Computer Science. Along the way I picked up a Mathematics major, as most in my program do. But when I mention my Professional Writing and Communication (PWC) minor, people do a double take. “Why?” they ask, with an expression equal parts confused and curious.

There is a consensus that art is separate from science. While science deals with objective facts, art focuses on self-expression. While science discovers the truth about the world, art discovers truths about society and self. Both are different, but not as much as one would think.

From a practical standpoint, it follows that science influences art. What one finds visually pleasing or not is dependent on the science of proportions like the Golden Ratio. Even in writing, readers love tricolon: a series of three parallel words, phrases, and clauses.

However, despite the obvious differences, art and science are both united by the mindset of the creator — be it the artist or the scientist — and certain attributes such as creativity, a questioning nature, and a desire to communicate.

Writing and coding exercise the same muscle

Writing code is a time-consuming process. I must face the question, “What is the purpose of this code?” Then, I must consider what tools I should use, and how to use them efficiently. As I test my code repeatedly, I change small pieces here and there, continually refining it to make it the best it can be.

Writing for The Medium is not too different. I must, again, face the question, “What is my article trying to say?” The delicate act of choosing words and stringing them together to convey my desired message, and the tedious editing that follows, is practically indistinguishable from the process of coding. I agonize over writing code the same way I agonize over my articles. This painstaking method of looking at your work is the creative process.

Problem solving and creativity are two sides of the same coin

It is difficult to see how mathematicians create proofs, and how programmers create programs. Problem-solving and critical thinking define a successful mathematician or computer scientist, but despite the evident rift between science and art, so does creativity. When starting a math problem, you only know two things: your starting assumptions, and your end results. Everything in between is the blank space that we need to fill up to find the answer. Somehow, we need to transform what we have in the beginning to get to what’s at the end.

In my experience, finding the answers requires the same inventiveness we see in art: step by step, we employ our mathematical tools to build a bridge between our original assumptions and the result. The beauty of it? There are multiple, maybe even infinite ways, to prove a proposition — or build a bridge. Each method is unique, using different theorems and branches. And in the process, new knowledge is created. That’s how all science works. Every day, scientists strain their brains to advance what we already know by discovering new knowledge. How is that different from an artist, who works to design something new from the world?

While scientists focus on creating knowledge about our world, artists focus on creating knowledge about society and the human experience. Both groups are trying to create something new. That creative process will always require imagination and the willingness to question the world around you.

To Question

Albert Einstein is one of the most famous scientists in history. His research on physics and the universe revolutionized the world and threw out conventions. The key component to his success was his rebellious and skeptical nature.

According to biographer Walter Isaacson, a recurring theme in Einstein’s life was his impulse to question everything around him. He questioned his religious beliefs, the system of learning in Germany, and other commonly held beliefs of the time. It was this nature that caused him to question the absolute nature of time and led him to the theory of special relativity.

Einstein’s personality represents the nature of all scientists: to constantly question the world around them. The same is true for artists.

When the world wanted natural and photorealistic paintings, Picasso, much like Einstein, questioned the necessity of such things, and ushered forth a new age of pushing the boundaries artists commonly used to express themselves at the time. Through paintings like the Guernica, he challenged authority and conventions.

While the domains of science and art differ, a combination of skepticism and relentless curiosity drives both artists and scientists to produce new knowledge.

Different Languages

The only difference between scientists and artists is the language they use. Artists use paints, musical notes, words, photos and instruments, to influence the world around them. Scientists use numbers, equations, theorems, and precise measurements to describe the same intricacies of the world that artists aim to capture and express. However different their methods, everything behind the scenes is the same, fundamentally.

With divisions like Arts and Sciences in education, many artists think they can’t be scientists, and vice versa. Many people in either field even think it’s a pain to learn about the other subject — a prominent example is how students groan about having to take distribution credits.

However, with the right mindset, you can easily switch from one to the other. All you have to do is use your imagination.

Features Editor (Volume 51); Associate Features Editor (Volume 50) — Madhav is a third year student completing a double major in mathematics and computer science, and a minor in professional writing. Everyone in UTM has a unique story that makes them special and deserves to be told. As the Features Editor, Madhav wants to narrate these types of stories with creative and descriptive writing. In his off-time, Madhav loves watching anime, reading manga or fantasy novels and listening to music.