Serial killers—pop culture’s newest entertainers

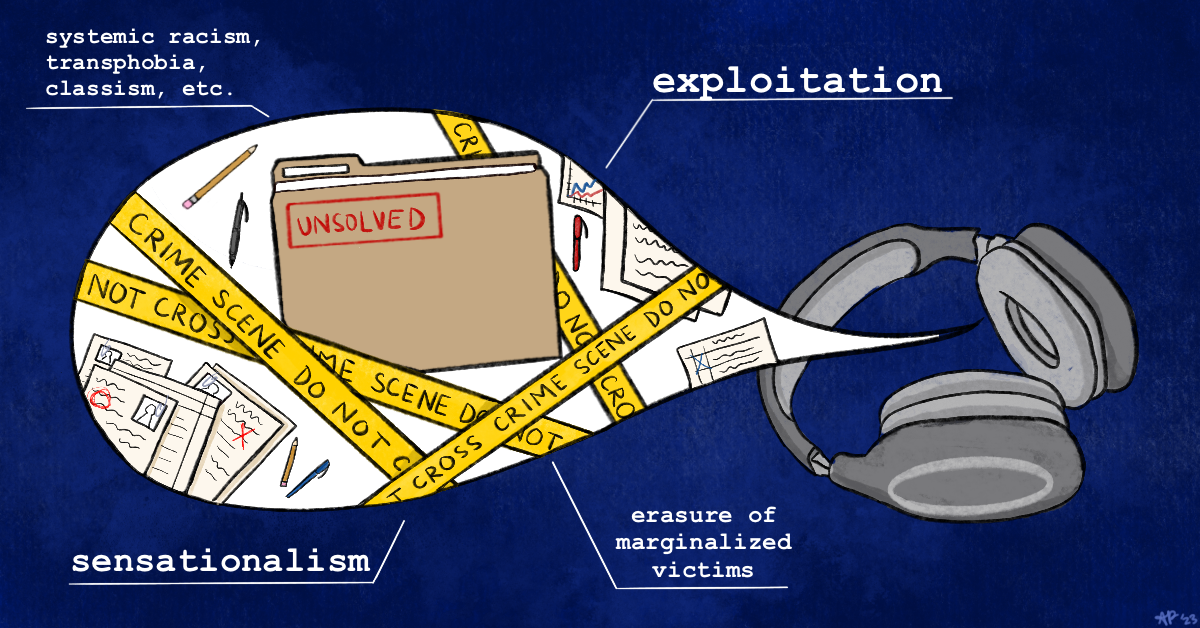

How the true crime media market thrives on hyper-consumption.

Trigger Warning: This article mentions sexual assault and extreme violence.

On Tuesday, January 10, 2023, the Beverly Hilton Hotel in Beverly Hills, California hosted the 80th Golden Globes Awards. After an industry “boycott” cancelled last year’s ceremony from airing—over ethical, social, and diversity issues—American powerhouse broadcasting company NBC announced award winners during a private online event in 2022 instead.

This year, however, once again displayed the glittery gathering of black-tie wearing stars in recognition of their recent contributions to (mostly Hollywood) film and television projects. Included in the full list of winners from that evening is actor Evan Peters.

Peters won “Best Performance by an Actor in a Limited Series, Anthology Series, or Television Motion Picture” for his portrayal of the titular character in Netflix’s Dahmer–Monster: The Jeffrey Dahmer Story. Jeffrey Dahmer is considered one of the most cold-blooded serial killers in American history.

Over the course of 13 years, Dahmer lured boys and young men first to his parental homes, and then to his own Milwaukee apartment where he, among other things, drugged, raped, strangled, and mutilated them. Upon Dahmer’s arrest in 1991, authorities found body parts belonging to the victims stored around his apartment. He was sentenced to 16 consecutive life terms for 17 of his known murders.

According to People magazine, Peters “sincerely hopes something good comes out of [the show].” Shirley Hughes, mother to a Dahmer victim, publicly criticized his Golden Globes win, as the surviving family members of Dahmer’s victims have “never seen a dime” from such series’ profits.

In an article published two days after the awards ceremony, Hughes told TMZ: “There’s a lot of sick people around the world, and people winning acting roles from playing killers keeps the obsession going and this makes sick people thrive on the fame.” What obsession is she talking about? The mainstream production and, might I add, habitual consumption of the true crime genre.

According to criminologist and Associate Professor Rebecca Scott Bray at the University of Sydney (USYD), “from what was once considered late-night low brow entertainment,” true crime podcasts, tv shows, films, and the like have garnered critical acclaim for helping at-home audiences understand dark psychology and criminal law.

“We’ve reached a point where people are no longer satisfied with reading, watching, or listening to true crime,” she says in a 2018 online news post. “They want to understand criminality and play an active part in how the justice system responds to crimes.” Are you watching and listening to true crime media to examine criminal behaviour and assess the shortcomings of law enforcement? Bray’s writing was basically an advertisement for USYD’s Criminology minor program that was being introduced at the time.

While some people’s intellects might feed their murder media diets, unless you’re actually studying criminology, forensic science, law, and what have you, may I be so bold in suggesting that we willfully tour the twisted worlds of deeply psychopathic minds because it’s simply thrilling?

Yes, we’ve reached a point where people are no longer satisfied with reading, watching, or listening to true crime. They want to talk about it with others to experience the kind of shock, intrigue, and recreational fun that was once specific to daily gossip circles.

True crime and horror entertainment experiences are a lot alike. Conventional horror film leitmotifs—the abnormal, gore, the infliction of pain, death, darkness—are present in true crime shows and films as well. To support the presentation of these themes, both genres use cinematic elements to create feelings of anxiety and anticipation.

Where a horror film might present suspenseful scenes and close-ups on door handles (“who’s trying to get in?!”), a true crime story is organized into a docuseries to achieve the same effect. An episode ends with unanswered questions that get settled in the next. The episodic TV structure, in other words, stretches out the narrative and thereby holds captive the attention of viewership.

In a 2019 review on research about what motivates us to watch scary movies, Dr. G Neil Martin, an honorary professor of Psychology at Regent’s University London in the United Kingdom, took note of an experiment that saw 60 children beneath the age of 10 appreciate suspenseful programs. Behavioural scientists say individuals prefer to watch movies that “maintain or maximize pleasurable states and achieve optimal levels of arousal.” Measurements of the children’s skin temperatures and heart rates declined when the suspense resolved.

According to an article published in the Journal of Communication in 2014, negative features of a film or TV show also steadily engage our cognitive and emotional selves. Though not pleasurable to view for most people, violence, for example—especially when it’s based on true stories and born of human actions—leads to self-reflection and “social gratifications, such as bonding while viewing intensely disturbing material.” True crime, it can be argued, is an indirect route to pleasure.

In 2022, NBC’s long-running sketch comedy show, Saturday Night Live (SNL), released a satiric music video that jokes about today’s casual viewing of murder shows. “Two sisters got killed on a cruise in the Bahamas, I’m going to half watch it while I fold my pajamas,” sings one SNL cast member. “Severed limbs found on a beach in Chula Vista, but I just kinda stare while I eat a piece of pizza,” sings another.

In the face of all the thrills that true crime clearly delivers, perhaps we run the risk of treating the genre as some compendium of cautionary tales or far-off narratives that could never personally touch us. Anyone can fall into the kind of grief that afflicts Mrs. Hughes when the story of her son’s death is picturized and made available through 24/7 streaming platforms. By virtue of our inherently broken human nature, many of us are capable of producing enough evil that would cause such a fall, too.

Sports & Health Editor (Volume 49)| sports@themedium.ca — Alisa is a third-year student completing a major in Professional Writing and Communication with a double minor in Political Science and Cinema Studies. She served as Editor-in-Chief of Mindwaves Volume 15 and Compass Volume 9 and was a recipient of the Harold Sonny Ladoo Book Prize for Creative Writing at UTM. Her personal essay, “In Pieces,” appears in the summer 2020 issue of The Puritan. In 2022, she published her first poetry chapbook, Post-Funeral Dance, with Anstruther Press and wrote for The Newcomer as a journalist. When Alisa isn’t writing, she’s probably reading historical nonfiction, ugly-crying over a sad K-drama, or dreaming of places far, far away.